The swearing-in of a new Congress is often marked by precipitous climbs and sudden tumbles. Last week, former Senate Minority Obstructionist Mitch McConnell realized his lifelong ambition of becoming majority leader; his rival Harry Reid backslid to his old role in the minority (though not before a less figurative fall sprinkled a little injury over the insult); and more than a dozen Republican senators took over as committee chairs, which contributed such marvelous ironies as global warming skeptic James Inhofe becoming America’s top gatekeeper for environmental legislation.

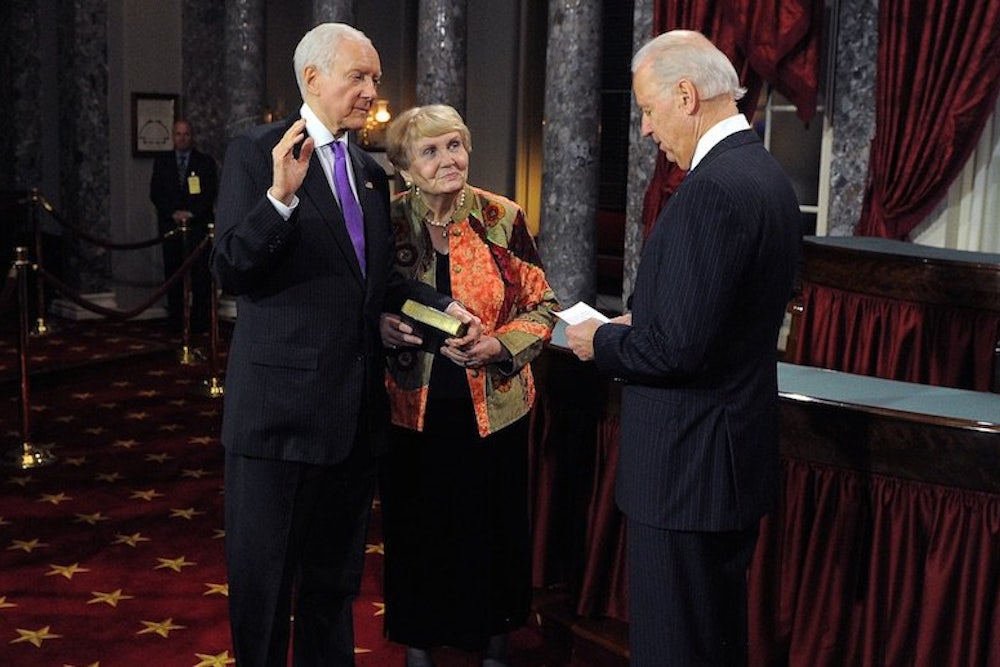

One of the most consequential changes, however, has passed virtually without comment. Coinciding with the rise of the new Republican majority in the upper chamber, Utah’s archconservative Senator Orrin Hatch is now the Senate president pro tempore. That means that he’s been transformed overnight from a minority-party graybeard to third in line to the presidency.

Most Americans probably didn’t realize that the good people of Beaver, Daggett, and Juab Counties had selected a possible future president for the rest of the country back in 2012, when they reelected Hatch to a seventh term. He is now the second Republican, behind Speaker John Boehner, in line to succeed the Democratic president and vice president in the event of their deaths, incapacitations, or resignations. Here is convincing proof, even more than the vice presidencies of Spiro Agnew and Dan Quayle were, that the voters, our political parties, and America's entire system of government don’t really take the issue of presidential succession seriously.

It almost never matters who the Senate president pro tempore is. The position is basically a constitutional quirk arising from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when the body occasionally had to call on a designated lawmaker to substitute for its normal presiding officer, the vice president. That function declined in importance over the last 60 years as veeps began to embrace a larger role outside the Senate. Thereafter a tradition arose to entrust the meager duties of the office (you get to sign legislation and administer oaths) to the longest-serving member of the majority party. That practice has frequently—one might even argue necessarily—resulted in the appointment of enfeebled old men from small states, often not of the president’s own party, to a position just a few heartbeats away from the big office.

Hatch is 80 years old, and he takes over the job from the comparatively spry Pat Leahy, a 74-year-old from Vermont. The two presidents pro tempore before Leahy were Hawaii’s Daniel Inuoye and West Virginia’s Robert Byrd, both of whom died in office at the ages of 92 and 86, respectively. Keep in mind that the oldest president in history, Ronald Reagan, left the White House at 77 already showing signs of the Alzheimer’s disease that would swiftly put an end to his public life. It’s flatly dangerous to put men of such advanced years anywhere near the Oval Office without the kind of rigorous medical vetting that presidential candidates receive during campaigns; if they assumed control over the government, it would almost certainly occur during a time of national crisis that would tax their abilities to the extreme.

Even if Hatch’s health and faculties could be guaranteed, his ascent would still mean the retroactive disenfranchisement of tens of millions of Democratic voters nationwide in favor of a vastly smaller group of some 600,000 Hatch voters from his home state—this at a time when national unity would be of paramount importance. This is doubly true of Boehner, a perfectly capable man whose entire congressional district consists of less than 800,000 people.

It may seem fanciful (or morose) to speculate on the subject of succession. After all, no Speakers outside of The West Wing have risen to replace a fallen president, let alone Senate presidents pro tempore. But we’ve lived far more dangerously than we ought to be comfortable with. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln originated in a plot to decapitate the government by also killing the vice president and secretary of state—one that very nearly succeeded. To pick an example of more recent vintage, United Airlines Flight 93 came within a forty-minute flight delay of wrecking the United States Capitol or White House. After 9/11, the joint Brookings/AEI Continuity of Government Commission issued a set of recommendations to help our succession process better reflect an age of global threats that strike without warning. Its counsel—to cut congressional and more junior cabinet secretaries out of the picture, as well as establish protocols for the appointment of temporary members of Congress and the judiciary—has gone thus far unheeded.

The group’s best suggestion was its most provocative: Instead of concentrating our entire crop of possible successors within the small area around Washington, where they are clearly vulnerable to a devastating act of terrorism, the president should select a small group of prominent Americans around the country who could be regularly briefed and prepared to step into power should the need arise. These figures—state governors, former cabinet officials, or other successful government administrators—could even be put forward by candidates during a presidential election, giving the public the partial opportunity to review and approve the choices (and providing political reporters and strategists with even more fodder). In the name of prudence, democracy, and a better news cycle, we should implement this plan—and for the same reasons, we should get elderly, out-party members of Congress some other ceremonial job.