Earlier this week, prompted by Representative Chris Van Hollen's ambitious plan to raise American wages, The Washington Post's Paul Waldman declared that Democrats will win the impending political fight about economic policy. “You have to look pretty hard to find an actual idea Republicans have,” Waldman wrote. “[V]oters will want to hear what the parties are going to propose to improve wages, working conditions, and the fortunes of the middle class and those struggling to join it. Winning that argument will be an enormously difficult task for the GOP, and they aren’t off to a promising start.”

The idea that Republicans have no new ideas has long been gospel on the left (including in these pages). In the 2012 election, liberals were correct to point out that Mitt Romney had no coherent agenda. His tax plan was mathematically impossible. He didn’t have a plan for the economy. On immigration, he suggested that undocumented immigrants “self-deport.” There was no plan to increase wages. It was a negative campaign, premised on the idea that a weak but improving economy would doom President Barack Obama.

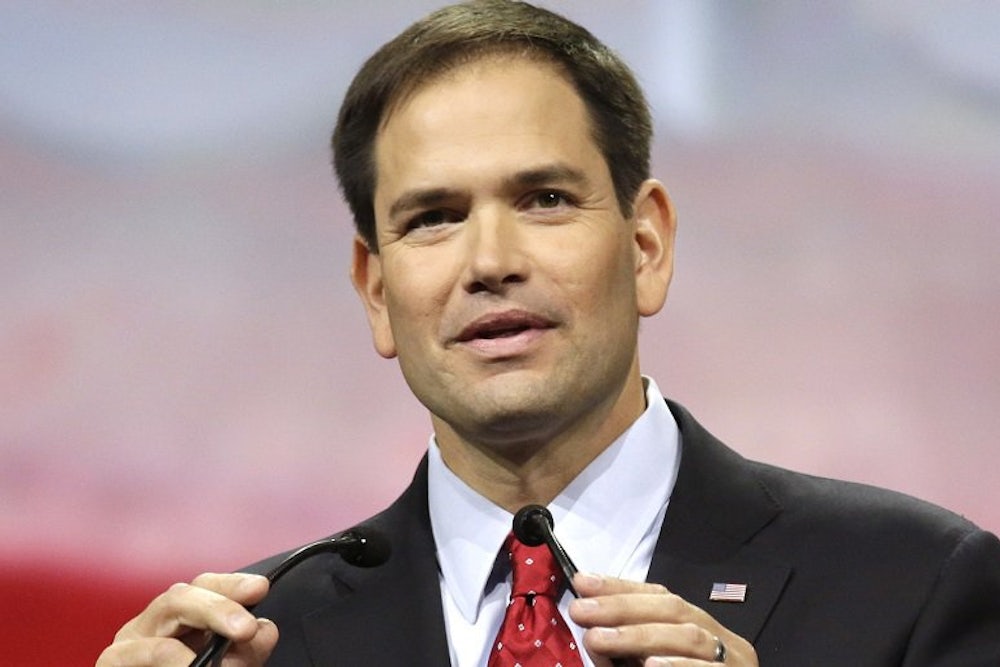

As Romney hints at a third presidential run, you can forgive liberals for expecting a 2012 redux where the Republican candidate, Romney or otherwise, offers the same old conservative ideas: cut spending, lower tax rates, and reduce regulations. And if that’s the case, Democrats, with Van Hollen’s agenda and a renewed focus on work-family policies, will be in good shape. But one candidate on the right is setting himself apart with a cohesive platform that extends from immigration reform to taxes to education policy: Florida Senator Marco Rubio.

On Monday, Rubio released his second book, American Dreams, which lays out his governing vision. Many of his ideas are predictably conservative, and he ignores several important issues, like climate change. But a few of his ideas are surprisingly palatable to liberals. If Rubio decides to run for president, and somehow emerges victorious from the GOP primary, he could give a Democratic nominee a run for her money; more likely, the eventual nominee will steal some of these ideas for ammunition in the general election.

But Rubio also poses an intriguing test for the Republican Party. American Dreams is more than a campaign stump speech in written form. It cements his membership with the so-called reformicons, an insider-outsider who is determined to modernize his party's policy (or, at least, to set himself apart from the GOP establishment). The next two years, as Rubio pushes and elaborates on the ideas in this book, will determine exactly how open the Republican Party is to that modernization. And that, in turn, will determine whether Rubio ends up in the White House in 2016—or ever.

American Dreams is undoubtedly a political book. He goes on about “restoring the American Dream” and criticizes President Obama at every opportunity. Some of those criticisms are objectively wrong. He attributes negative GDP growth in the first quarter of 2014 to an economy in decline under Obama, when nearly all economists blame the unusually harsh winter, and calls Obamacare “the single largest impediment to job creation in the United States.”

But that's just Rubio preserving his conservative credentials, as any potential Republican presidential candidate must. But what really sets Rubio’s book apart from his peers' is the positive governing agenda he lays out, much of which he developed and rolled out in 2014. Here are his key ideas:

Family-friendly tax reform

Rubio is working with Utah Senator Mike Lee on a tax plan that would expand the Child Tax Credit and allow it to offset both income and payroll tax liabilities. He would also cut the number of tax brackets from seven to two, one at 15 percent and one at 35 percent. Expanding the CTC is a good idea; condensing the number of tax brackets is unnecessary.

There’s a problem here: Rubio never says if his plan is deficit-neutral. Lee offered a very similar tax plan in 2013, but he had to revise it after the Tax Policy Center found it would reduce revenues by $2.4 trillion over the next decade. Rubio has teamed with Lee, and they're expected to release a revised version of Lee’s plan this year. Given the TPC’s original score of Lee’s plan, it will be difficult for the senators to make it deficit neutral by closing tax breaks. It may be telling that Rubio omitted any pledge to deficit-neutrality in his book.

Antipoverty reform

There are two main components to Rubio’s antipoverty platform.

First, he would expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), transforming it into a wage subsidy that would be available equally to working parents and childless, working adults. Right now, EITC benefits accrue almost entirely to low-income workers with kids. Childless adults receive almost nothing. Rubio isn’t alone in wanting to fix this flaw; Obama and Senator Patty Murray have proposed the same tweak. But in Obama and Murray’s plans, the EITC’s expansion would be funded by increasing taxes elsewhere. Rubio’s plan doesn’t have a funding source—he promises to keep EITC benefits for working parents unchanged, increase them for childless workers, and keep the entire thing deficit neutral. That math doesn’t work.1

Second, Rubio would consolidate the dozens of antipoverty programs into one “Flex Fund” which would then distribute the money to the states in lump sum payments. Those payments would depend on the number of people in poverty, but they would not decrease if states reduced poverty. Liberals are right to worry that this can be a back-door to cutting total antipoverty spending. Rubio would need to devise a way to restrain states from reducing their own antipoverty spending in response to the fed’s lump sum payments. But such restraints have been historically hard to devise, with states often finding ways around them.

Immigration reform

For legal immigration, Rubio suggests moving to a merit-based system instead of a family-based policy. But like all conservative proposals, Rubio’s is premised on increasing border security in ways that are “verifiable.” He never elaborates how strict these verifiable measures would be—a key question that could decide whether a compromise could garner Democratic support. Current Republican proposals set such a high bar for border security that it is nearly impossible to meet them. If that’s what Rubio has in mind, Democrats will ignore his plan.

Beyond that, once those unspecified border metrics are met, Rubio would allow the undocumented immigrants to apply for temporary nonimmigrant status after paying an application fee, learning English, and undergoing a background check. After a decade, they could apply for permanent residency. What Rubio doesn’t mention in the book, but did note in an interview with the New York Times, is that that permanent residency eventually allows those immigrants to apply for citizenship.2 Depending on the border security metrics, this is a reasonable proposal that could be the basis for a compromise with Democrats. But without those details, it’s impossible to know for sure.

Replace Obamacare

Rubio would repeal Obamacare, but he also deems a replacement necessary. “[I]t would be a huge disservice to the American people to allow our health care system to collapse just to make a political point,” he writes. In turn, he is working with Representative Paul Ryan on a plan that would eventually eliminate the tax preference for employer-sponsored health insurance and replace it with a credit for each individual—a smart idea that health economists have long supported. That would be highly disruptive to the insurance market, much more than Obamacare has been, so Rubio has tried to smooth that transition by phasing out the deduction for employer sponsored insurance over 10 years. But it will be a politically challenging transition, if it ever comes to pass.

The new plan would also adopt other traditional conservative ideas, like expanding access to Health Savings Accounts and allowing states to sell insurance across state lines. But much of it remains vague. There’s nothing about covering people with pre-existing conditions, for instance. We'll have to wait until Rubio and Ryan unveil their plan to know more.

The rest

Rubio's Social Security plan has some good ideas, like opening up government retirement plans to all Americans. He would turn Medicare into a premium support system. He has two ideas to make college more affordable: make income-based repayment the default payback option for students—a very smart idea—and create a market in students, so that investors could pay for a kid’s college education and receive a fixed percentage of the kid’s income for a certain number of years after graduation (that would be tightly regulated). He would also give high school kids more flexibility to use their time for technical training, although the funding source on that is also murky.

The book is also notable for what's not in it. Other than climate change, he doesn’t mention monetary policy, which, given its importance to the economy, is a glaring weakness of his agenda (although one that almost every other politician shares). Unlike most of his peers, he focuses very little on deficit reduction—it only directly appears in the afterword, where he calls the debt “one of the greatest risks to our national security.”

Even with these omissions, Rubio has put together an impressive collection of new ideas, some of them ones that liberals will like. If the ideas ever became closer to becoming law, Rubio would have to fill in the blanks. That won't be easy. Money has to come from somewhere, and Rubio has put himself in a tough position with some of these plans. But the contours of the plans are there, and Democrats would do well not to ignore them.

With American Dreams, Rubio has put himself in a perilous position within a party that's been slow to adopt new ideas. On taxes, for instance, the conservative establishment remains focused on cutting marginal tax rates rather than expanding the Child Tax Credit. Kim Strassel, an editorial board member at the Wall Street Journal, and other conservatives have been hostile to Rubio’s plan. Despite his work with Rubio on health reform, Paul Ryan is still an ardent supply-sider on taxes. It’s not a stretch to say that Rubio would have to upend the last half century of conservative thinking on taxes for his plan to prevail.

And yet, he has not demurred. Why? Why is he seemingly taking such a risk within the Republican Party? Perhaps he's trying to pull his party into the 21st century. Or perhaps he doesn't want to renovate his party's rotting agenda—he just wants to slap a fresh coat of paint on it. Or perhaps Rubio is playing the long game. At just 43 years old, he will be the same age in 2040 as Hillary Clinton will be in 2016. His political career is just beginning. He could still compete for the Republican nomination this cycle, although that seems less likely with Jeb Bush all but officially running. As a young, Hispanic from Florida, Rubio will surely be an attractive running mate for whomever prevails in the GOP primary.

But he has many other options as well. He could seek the Florida governorship in 2018 and gain some actual governing experience before embarking on a presidential campaign. Then, in 2020 or 2024, he could make a serious run for the White House with a loaded resume. Or he could stay in the Senate, continue to work the power levers, convert more of his peers to reform conservatism, and further develop his platform (all while expanding his fundraising connections, of course).

Whatever questions American Dreams raises, it does make one thing clear by contrast: The Republican Party is bereft of new ideas. After six years of obstructionism, the Party of No needs a positive governing agenda. Rubio has one. No doubt the Republican establishment will oppose a number of the proposals in this book, if not ignore them outright. But much like Democrats, the GOP would be doing so at its own risk.

On "The Daily Show" Tuesday night, where Rubio appeared to promote his book, Jon Stewart asked him where the money for the EITC expansion comes from. He avoided the question multiple times.

Rubio even writes in his book that those who seek permanent residency wouldn’t have “any special pathway,” clearly a move to calm conservatives who think he betrayed the base two years ago by proposing a plan with a pathway to citizenship. That’s undoubtedly why he doesn’t mention that this plan effectively has a pathway to citizenship as well.