With Ukraine in continued crisis and Moscow deflating under a crippled ruble, the European Union has begun scouring for non-Russian gas. Azerbaijan, in the gas-rich southern Caspian, should present a natural replacement.

But progress on the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), one of the chief vehicles for moving Azeri carbon to eager European markets, has not advanced with the alacrity officials in the capital city of Baku had hoped. Environmental organizations and civil groups have pushed back at the planned pipeline—set to connect to the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline, which will help bring Azeri gas to southern Italy—by pointing to its threat to farmers and fragile marine habitats.

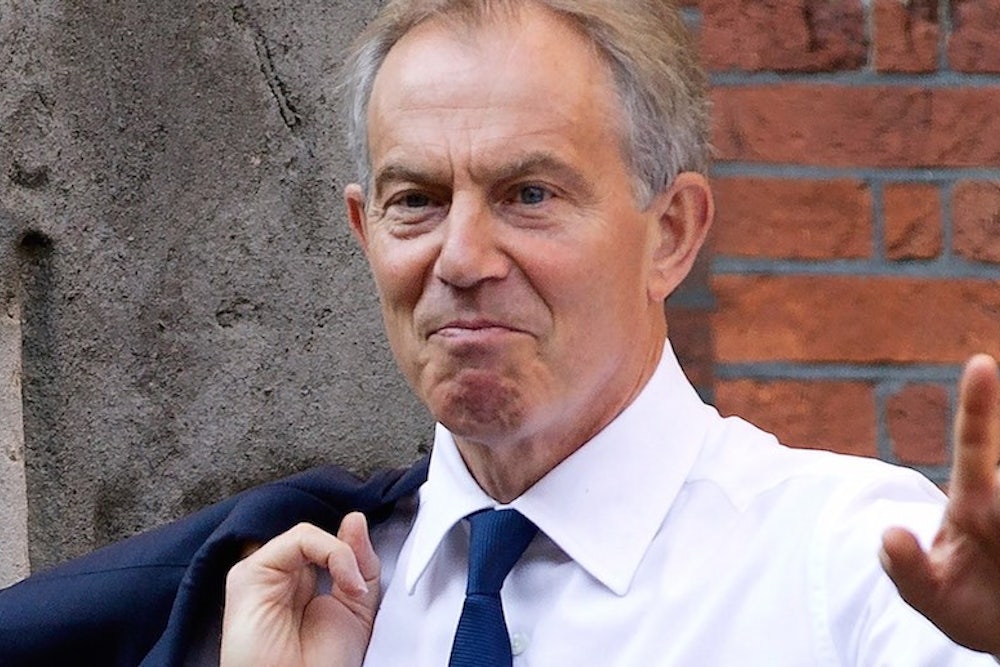

Instead of waiting to see whether the fracture between Moscow and Brussels would accelerate the pipeline’s construction, the consortium spearheading the project, including BP, turned to a familiar face: former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. The move, based on the scant information on the relationship available since the July announcement, comes with the presumption that Blair’s presence will smooth the pipeline's remaining obstacles. One senior official at Azerbaijan’s state-run gas company told this reporter Blair’s hiring brought “knowledge and expertise,” but offered scant detail. Perhaps that's because Blair’s presence seems gauged to help assuage continued concerns in working with one of the most notoriously authoritarian nations in the region.

This won’t be the first time Blair has helped to inflate Baku’s coffers. While prime minister, Blair helped guarantee the completion of the Baku-Ceyhan-Tbilisi pipeline, ending Russia’s chokehold on post-Soviet hydrocarbon transit. After leaving office, Blair continued to buff Baku’s image. In 2009, he gave a speech in Azerbaijan—for a price of nearly $150,000—to bless a new methanol plant. Rather than highlighting Baku’s backslide toward autocracy, Blair entirely ignored Azerbaijan’s rights clampdown at the time, and seems to have remained mute among calls to donate his fee to charity.

That was 2009, when Baku could tout some civil and media rights, and Blair could discuss Azerbaijan’s “very positive and exciting vision for the future” with some semblance of plausible deniability. Now Azerbaijan’s civil space, the room for dissent and democratic lobbying, has withered as quickly as any post-Soviet nation has seen in recent years, outpacing even Russia’s rate of repression in the years since. Journalists and human rights activists have been intensely harassed and savagely beaten. Political opposition stand imprisoned with little legal recourse. Even U.S. citizens haven’t proven immune to Baku’s bludgeon. The deterioration of civil and media space in Baku has gotten so bad that former U.S. State Department officials, including a former ambassador to Azerbaijan, have—despite Baku’s remarkable ability to find hacks willing to lobby on its behalf in American publications—begun publicly pushing for sanctions on Baku’s ruling claque.

With his second go-round helping burnish Baku, Blair is solidifying a pattern of helping post-Soviet autocrats expand influence and economic reach. His work with Azerbaijan, in fact, pales in comparison to his time spent working with the repressive Kazakhstani government. While the former prime minister’s foreign policy failures are largely remembered in the embers of Iraq, his work in Kazakhstan presents what could be his great post-premiership fiasco. Since he came aboard in 2011, Kazakhstan experienced its worst-ever civil rights backslide: government-led massacres, political opponents jailed, steep declines in international rights rankings. Blair, meanwhile, appears to have gotten himself and his closest colleagues handsomely paid.

Following the dust-hole image Sacha Baron Cohen’s 2006 film Borat reified, seething Kazakhstani officials in Astana decided to combat the notion that their nation was awash in anti-Semitism and public pubic hair. Kazakhstan began a full-court PR assault, landing op-eds in the New York Times, obscured sponsorship of positive coverage on CNN, and forming an “International Advisory Board,” stacked with Western dignitaries, to promote Kazakhstan’s image internationally. Meanwhile, questionable academic reports sought to paint Kazakhstan as some halcyon land of freedoms and sound governance.

In 2011, in the midst of this public relations blitz—much of it similar to what we’ve recently seen out of Azerbaijan—Kazakhstan decided to hire Blair as an “official adviser.” Per his office, Blair’s aim in Kazakhstan centered on his “Policy Advisory Group,” and would focus on “reforms … identified by the EU and others as necessary for Kazakhstan’s future development.” The advisory group would be tasked with moving Kazakhstan toward the developed country it aimed to become. And Blair would be the man to lead the advisory charge.

From the beginning, misdirection surrounded Blair’s role. Instead of being brought aboard to spear reforms, as he claimed, the Financial Times reported that Kazakhstan had sought his services to help the country “present a better face to the west”—focusing, as The New Republic reported, on redeeming its autocratic President Nursultan Nazarbayev, in power for 25 years. The Telegraph even suggested that Blair’s job was to spin Nazarbayev’s willingness to give up Soviet-era nuclear weaponry as reason to award him a Nobel Peace Prize—though Blair would not be the first to make such a pitch, with U.S. representatives Darrell Issa and Eni Faleomavaega having stated that Nazarbayev deserved the prize. (It didn’t help when Blair claimed that Kazakhstan was the only nation to have given up nuclear weapons: Ukraine publicly abandoned its nukes as well.)

Kazakhstan's Foreign Ministry claimed that Blair’s work was intended to “increase the investment attractiveness of the republic”—which was backed up by a 2011 video in which Blair extolled his experiences in Kazakhstan, claiming it was “a country that is almost unique, I would say, in its cultural diversity and the way it brings different faiths together, and cultures together.” Ignoring the fact that Kazakhstan’s religious restrictions spiked significantly during Blair’s time with Kazakhstan, Blair unabashedly sold Astana’s line that the country stands as an island of stability. Blair repeated such talking points in recent interviews with the Wall Street Journal and Vanity Fair.

Questions about the former prime minister’s involvement in Kazakhstan flared again recently. A 2012 letter from Blair to Nazarbayev surfaced in August, in which Blair offered recommendations on how the Kazakhstani president should address the 2011 Zhanaozen massacre, which saw at least 14 unarmed protesters die at the hands of government forces. Instead of centering on the Zhanaozen events—i.e., recommending Nazarbayev push for an international investigation, or take some form of public responsibility—Blair advised the autocrat to remind the audience that the deaths, “tragic though they were, should not obscure the enormous progress” in Kazakhstan. Blair included about 500 words of recommended text for Nazarbayev’s upcoming speech—effectively becoming the speechwriter for an aging despot whose regime had just slaughtered its citizens. “This is a very concrete and very worrying piece of evidence,” Hugh Williamson, Human Rights Watch’s director of Europe and Central Asia Division, said. “It’s clear this was part of his contract on how to present in a very positive way such a terrible incident, and it’s rather sort of disgusting how he’s gone about it. … It’s a cynical effort to sort of spin the story.”

Blair’s price for these services remains shrouded. Bloomberg reported that Blair’s contract with Astana would pay his team $13 million annually, while Kazakhstani media reported the deal could be worth nearly $27 million a year. Blair's camp denied both figures, noting not only that the final amount was “obviously confidential” but that Blair himself would never see a penny of the funds; the final amount, instead, would fund his charities. A statement from Tony Blair Associates to this reporter reiterated that the compensation “does not go to Mr. Blair personally.”

Even if Blair never sees any direct remuneration from Astana within this specific contract, his work with Kazakhstan has coincided with a series of conspicuous business arrangements between the Kazakhstani government and those close to Blair, as well as with one of Blair’s most lucrative companies. According to a spokesman for Tony Blair Associates, Kazakhstan’s decision to hire Blair came concomitant with the government’s decision to hire an organization called Windrush Ventures Limited. As the spokesperson told this reporter, “[Kazakhstan] hired Tony Blair Associates, which is the umbrella name for” Windrush and another commercial organization. Windrush, as it turns out, is nearly indistinguishable from the Office of Tony Blair. And as Bloomberg found, Windrush happens to be one of Blair’s most profitable companies, having booked some 16 million pounds in 2012.

Convoluted commercial structures aside, it’s clear that upon Windrush’s hire by Kazakhstan, the company subsequently contracted the London-based Portland Communications for “public affairs and consulting and media activities” in the United States, according to the Foreign Agents Registration Act database. Portland, as it happens, was founded by Tim Allan, Blair’s former adviser and public relations chief. The company promptly began covering Kazakhstan’s “discernible appetite for political reform.” A EurasiaNet investigation, on the other hand, found that computers in Portland’s offices also manipulated Wikipedia entries to obscure the role political opposition played in the exile of Mukhtar Ablyazov, an opponent of Nazarbayev who had applied for asylum in the United Kingdom. (Portland did not return repeated requests for comment.) The president of BGR Gabara, the second company listed in the FARA documents as representing Kazakhstan, noted that his company no longer represents Kazakhstan—meaning that, according to the most recent documentation, Portland Communications is the only public relations company representing Kazakhstani interests in the United States.

It remains entirely possible that Blair, as he has claimed, has not yet seen any personal profit from his position with the Kazakhstani government. However, it has become clear that his advisory role with Astana came with the hire of one of his most profitable companies—which, in turn, hired a company founded by one of Blair’s associates to help buff Kazakhstan’s reputation.

That job is only becoming more difficult. Blair's presence has coincided with the country’s greatest backslide in civil and media rights since Kazakhstan won independence in 1991. By nearly any metric, Kazakhstan has devolved into a repressive, carbon-based autocracy, shedding any pretense of political plurality or media freedom. Indeed, in the three years since Blair’s hire, the country has retained its “Not Free” ranking from Freedom House and slid six places in both Reports Without Borders’ annual press freedom ranks, to 161 out of 180, and Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, to 126 out of 177. Even more remarkably, since Blair’s hire, Kazakhstan has fallen 18 spots in the World Bank’s Doing Business index, to 77 out of 189. All of this came on top of the Zhanaozen massacre, which, according to Blair, shouldn’t distract from all the other progress Kazakhstan has apparently made.

In 2013 Williamson attempted to clarify Blair’s role in Astana. Blair deflected, addressing instead Kazakhstan’s struggles with “extremism”—as non-existent a threat in a Muslim-majority nation as you’ll find—and insisting that his work was “completely in line with the direction the international community wants Kazakhstan to take.”

Whatever this “international community” comprised, Blair did not explain. Williamson, meanwhile, observed that Blair “had been indifferent to those suffering abuses [in Kazakhstan] and given a veneer of respectability during a severe crackdown on human rights.” Three years after Blair was hired, political, civil, and media rights in Kazakhstan stand more battered than they’ve been at any other point during independence.

As Blair turns to aiding Azerbaijan’s hydrocarbon expansion, there's no reason to expect things to go any differently in Baku.

Blair’s push for the pipeline will buff Baku’s image. It couldn’t come at a worse time for those who wish democratization and media freedoms for Azerbaijan. Considering Blair’s messy history of promoting democracy as prime minister, it shouldn't shock that his presence accompanies the direct antithesis. For those in suffering in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan—like those in Iraq—Blair’s presence amounts to a toxin for democratization.