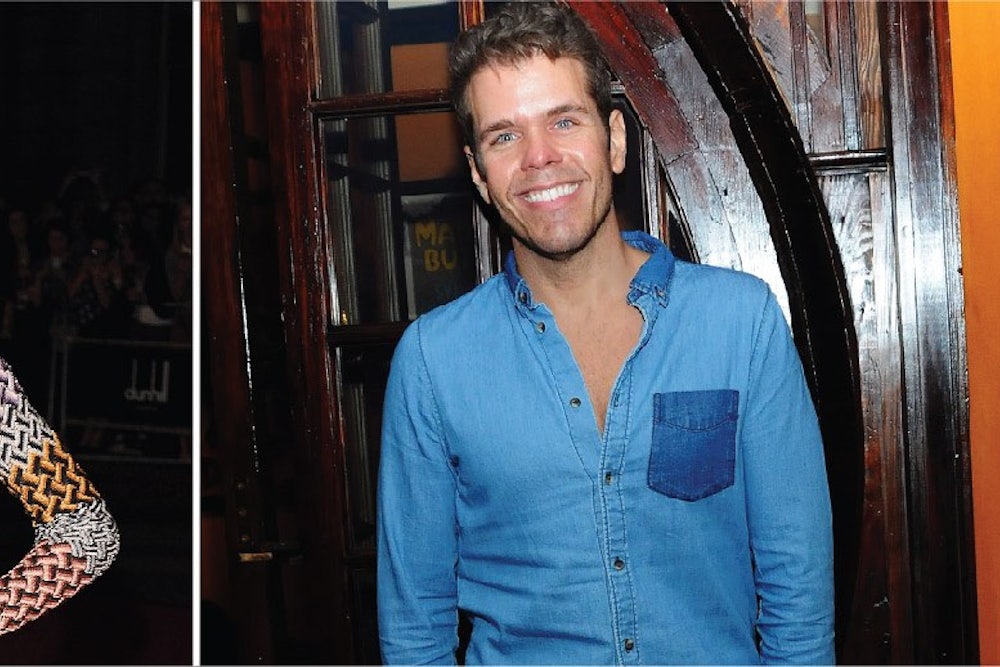

Usually portrayed—often simplistically—as ironclad, the bonds between gay men and straight women have been the focus of much debate lately. Actress Rose McGowan caused a stir last month when she described gay men as “as misogynistic as straight men, if not more so” and blasted gay men for not standing up more for women's rights. More recently, rapper Azealia Banks echoed McGowan's remarks as she reignited her Twitter feud with blogger Perez Hilton, once again calling him a “faggot,” all in the process of attempting to redefine the term as “any man that hates women.”

While both women took flak for their remarks, it's too easy to dismiss their criticisms outright. McGowan is hardly alone in her belief that gay men are generally myopic about the rights of other oppressed groups. And Perez's mockery of the fashion, makeup, and lifestyle choices of famous women is viewed by many as misogynistic. Moreover, the LGBT rights movement has more than once been accused of sexism (and racism) in the past, with the faces and voices of the movement usually dominated by photogenic white males.

Despite the prevalence of straight woman/gay man best friend cliches, it's fair to say that gay men's relationships with and attitudes toward women are often more complex than what's portrayed in your typical episode of “Will and Grace.” Still, complexity is not evidence of misogyny, and to claim that gay men are misogynistic depends on how you classify what constitutes misogyny.

Certainly, the humor that gay men engage in can flirt with misogyny. From the gossipy slut-shaming of Hilton's blog to the campy bitchfest that is RuPaul's Drag Race, gay men have long been known to engage in the kind of politically incorrect, biting repartee that often makes women the butt of the joke. But misogyny manifests itself not just in jest. Who among the LGBT community can claim to not know any of the following types of gay men: Men whose social circle consists almost exclusively of other gay men. Men who routinely say the body parts and sexuality of women are gross. Men who express an aversion to lesbians, or who tend to stereotype them and/or dismiss their concerns. Men who write “no femmes” or, even worse, “straight acting” on their Grindr profiles. Men who call their best female friends “fag hags” or “fruit flies” and who put them down routinely while dragging them to gay bars or dance clubs?

This is reductive, to be sure. Not all gay men do this—not even most do. But if we know examples of at least some of these men in our midst, doesn't it behoove us to stop acting as if all of this is fine by us? The gay rights movement has largely succeeded in convincing the world that LGBT folk are “normal” but, perhaps as a side effect of these assimilationist tendencies, it has taken on some of the unfortunate baggage associated with mainstream culture, including its misogyny. Wanting to be mainstream often means adhering to the expectations of the dominant culture, in this case a white male heterosexual culture which routinely views women as the weaker, more emotional, more frivolous sex. Gay men are still mocked for their tendencies to be histrionic, demonstrative, and emotional—i.e. “feminine” and “weak." Should we be surprised, then, that so many gay men have internalized these criticisms and, in an attempt to demonstrate their “masculinity,” demean women in the process?

In his documentary, Do I Sound Gay?, to be released next year by IFC/Sundance Selects, David Thorpe frets over his long-standing insecurities about his voice and speech. In seeking to find the root causes for the speech patterns that many gay men share, he interviews gay celebrities, voice coaches, and linguists and discovers that his deep aversion for “sounding gay” is shared by many other gay men. In doing so, however, he soon recognizes that the process of trying to “explain” the voices of gay men is itself a byproduct of a kind of internalized homophobia as well as misogyny.

Would gay men really be so uncomfortable with the way they sound had they not experienced so much criticism and abuse about it while growing up? Even men who ostensibly seem comfortable with their sexuality, such as humorist David Sedaris, reveal their anxieties in the film. Sedaris states that when someone tells him that they didn't know he was gay, it makes him feel good, and he wonders why that is, considering that he thought himself “beyond all that.”

Perhaps gay men aren't beyond all that. A tendency to fetishize hypermasculinity, to exalt “tops” over “bottoms,” and to disparage men who are effeminate persists among gay men until this day, despite the fact that these feelings no doubt stem in part as a response to all the comments hurled their way when they were younger. It seems only natural, once you've internalized feelings of inadequacy and self-loathing, to want to demonstrate that you're not what other people say you are, or worse, that you're not as queer as those other gay men over there, especially if the very tribe you're a part of seems to be as much on board with these assumptions as the straight culture.

But it's worth remembering that millions of gay men strongly support women both in their actions and beliefs—in their political alignments and voting records, for instance—and demonstrate a distinctly feminist worldview. It's important then, to distinguish the kind of misogyny that gay men might demonstrate from the kind of misogyny coming from straight men, the kind we associate with sexual harassment, rape culture, political oppression, and violence. For gay men, misogyny seems to be borne out of a subconscious desire to be accepted—by their gay male peers and society at large, which has told them that sounding “feminine” is not ideal and that being a man often means making fun of or belittling the concerns of women. In some ways this is an extension of the straight locker room culture, with gay men may simply doing what society expects all men to do (even as it doesn't condone it). This tendency to conform with accepted gender roles can also be seen in the idealization of hypermasculine men as well as in drag culture, where telling a queen she's “fishy” (i.e., most naturally feminine) is the best compliment you can give her. Even the aversion to lesbians that some gay men have can likely be attributed to these women's refusal to adhere to gender norms.

With the fluidity of gender today—and with an increasing acceptance of transgender men and women as well as other expressions of identity—it's possible we may be moving away from these narrow definitions of masculine and feminine, and with it, from some of the lingering shame gay men have, which might manifest itself in these more subtle forms of misogyny. Gay men should be less afraid of embracing their feminine tendencies, which, after all, are also associated with qualities of kindness, compassion, and empathy. Being proud to be gay should mean being proud of whatever way your gayness expresses itself, and accepting the traits that you possess without having to classify them—much in the same way that straight women have treated gay men for so long now.