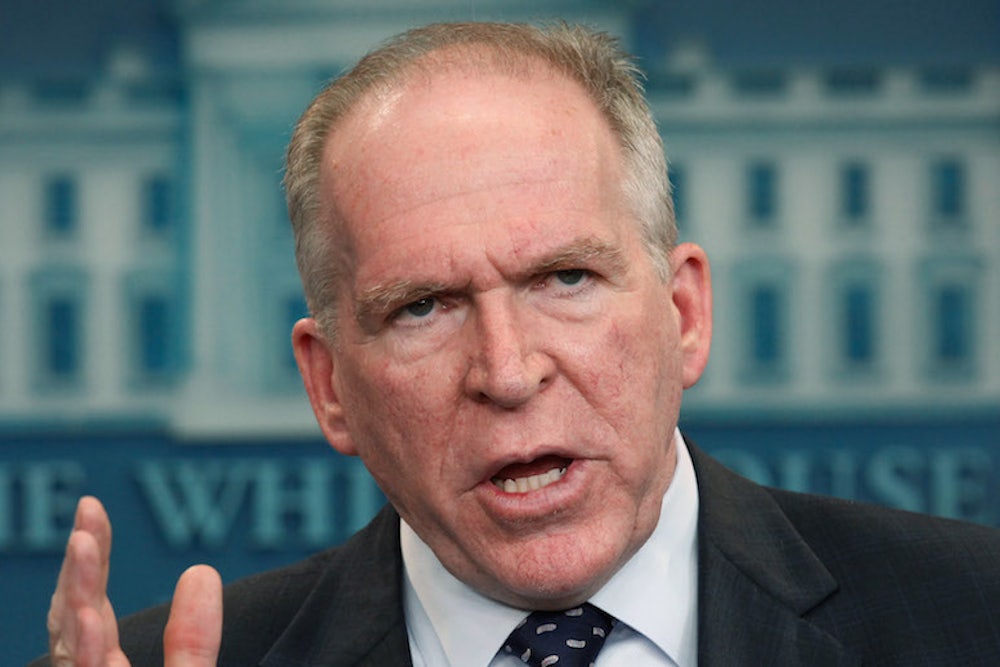

Speaking from the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, Director John Brennan gave a 45-minute televised press conference on Thursday afternoon. Reporters in attendance repeatedly asked Brennan to confirm his stance on the effectiveness of torture in producing useful intelligence information. He responded:

Detainees who were subjected to EITs [enhanced interrogation techniques] at some point during their confinement subsequently provided information that our experts found to be useful and valuable in our counterterrorism efforts, and the cause and effect relationship between the application of those EITs and the ultimate provision of information is unknown and unknowable.

Senator Dianne Feinstein and her supporters were pushing Brennan to take a firm stance that torture never works. And there is extensive evidence that torture is a terrible way to produce reliable information because people will say anything to make the pain stop. But Brennan is correct in saying that in the specific case of these prisoners, there is no absolute way to differentiate between information provided voluntarily versus coercively.

Once torture has been used against an individual, it is impossible to know if information they subsequently provide is a product of that torture, or would have been offered anyway. Even months later, in a seemingly voluntarily situation, he could still be speaking out of fear of that prior experience. (This is not to say there is no way of knowing if other interrogation methods work. Ali Soufan proved years ago that non-violent questioning is effective.)

Brennan’s point unintentionally undermines the legitimacy of the military commissions at Guantánamo Bay, whose defenders proudly tout that the 2009 Military Commissions Act does not allow evidence obtained by torture to be used. No doubt, this clause is a big improvement from President George W. Bush’s 2001 executive order, which said:

Given the danger to the safety of the United States and the nature of international terrorism … it is not practicable to apply in military commissions under this order the principles of law and the rules of evidence generally recognized in the trial of criminal cases in the United States district courts.

But the prohibition against torture-tainted evidence is simply not realistic, for the same reasons that Brennan cannot conclusively say that torture did not produce valuable intelligence. Once torture has occurred, it is impossible to separate pieces of information into categories of “arising from torture” and “not arising from torture.” All evidence extracted from Guantánamo detainees who were exposed to the CIA’s torture program is irreparably tainted.