In 2009, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) embarked on what was intended to be a yearlong investigation into the CIA’s enhanced interrogation program—now less euphemistically described as a torture program. After five years, $40 million, the loss of support from the Committee’s Republicans, and an epic falling-out between Committee Chairwoman Dianne Feinstein and the intelligence agency, the committee released the 525-page executive summary of the 6,000 page report. “The CIA’s actions are a stain on our values and our history,” Senator Feinstein said as she introduced the report Tuesday morning.

The CIA pushed back on the Senate report, claiming that it “provided an incomplete and selective picture of what happened.” Republican members of the Committee simultaneously released their own report, alleging that the study “appears to be more of an exercise of partisan politics than effective congressional oversight of the intelligence community.”

Politics aside, the SSCI report unearthed internal CIA documents and communications that prove the already discredited torture program to be more brutal and less effective than the public had been led to believe.

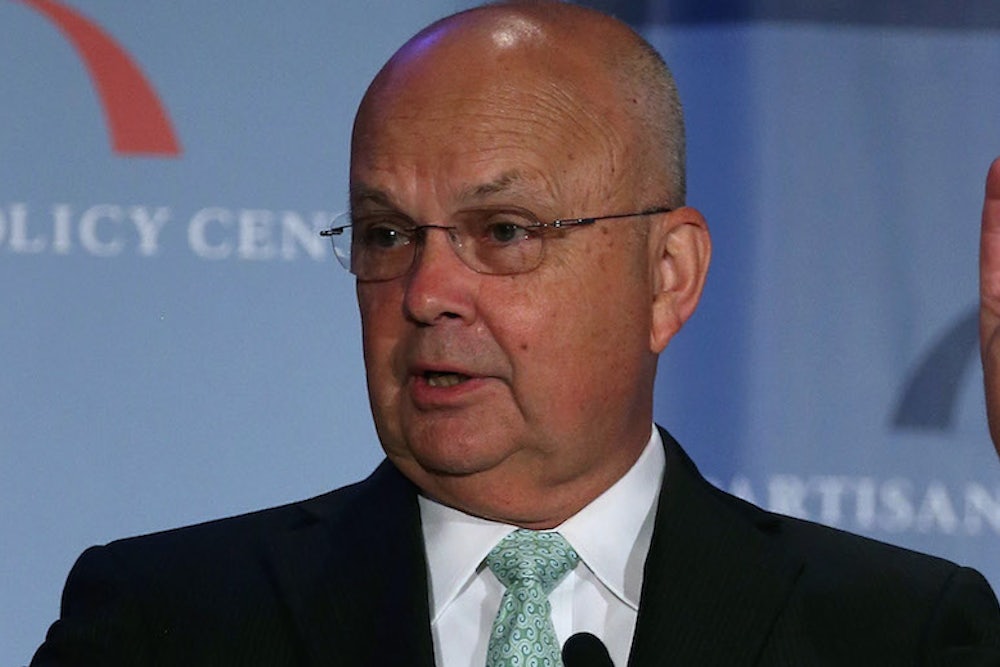

In 2007, former CIA Director Michael Hayden maintained, “all those involved in the questioning of detainees have been carefully chosen and screened for professional judgment and maturity.” But members of the team included people who confessed to anger management problems and a history of sexual assault. In 2002, there was a push within the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center (CTC) to assume vetting responsibilities for personnel using “enhanced interrogation techniques.” CTC Director Jose Rodriguez shut the idea down. “I do not think that CTC/LEGL should or would want to get into the business of vetting participants, observers, instructors or others that are involved in this program. It is simply not your job,” he wrote in an email.

Hayden also assured the Senate committee that all interrogation techniques were “used against American service personnel during their training.” He told senators, “Once [a detainee] gets into the situation of sustained cooperation” debriefings are “not significantly different than what you and I are doing right now.” Furthermore, the CIA claimed that their interrogation practices did not deviate from the measures approved by Justice Department lawyers in 2002 and 2005. The most serious injury suffered by a detainee during the interrogation program was light bruising from the shackles used during waterboarding, according to Hayden. The findings of the Senate committee report prove these claims to be patently false.

Abu Zubaydah, who was waterboarded 83 times, became “completely unresponsive with bubbles rising through his open full mouth” during one round of the process. He was unconscious even after being tilted upright, and did not regain consciousness until receiving the Heimlich maneuver. The Justice Department’s legal memos, which the CIA claimed to adhere to, provided strict limitations on waterboarding: a maximum of 40 seconds per application (the CIA told the Justice Department that this maximum was rarely reached), no more than twice in 24 hours. The memos also indicated that waterboarding should cause fear but not physical pain. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times total, received the treatment five times in a period of 25 hours—one session lasted 12 minutes.

Again branching outside of methods approved by Justice Department lawyers, the CIA subjected at least five detainees to “rectal feeding” and “rectal rehydration” without documenting medical need. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s interrogators ordered rectal rehydration as a way of showing “total control over the detainee.” Interrogators pureed the lunch tray of a detainee named Majid Khan and rectally infused the mixture of hummus, pasta, nuts, sauce, and raisins. Another detainee subjected to rectal feeding, Mustafa al-Hawsawi, was diagnosed with chronic hemorrhoids, an anal fissure, and symptomatic rectal prolapse after rectal feedings. Meanwhile, detainees were denied toilets or buckets to defecate in, and were instead given diapers. When one detainee asked for his bucket to be returned to his cell, he was told, “all rewards must be earned.”

In an interrogation session that deviates starkly from even the most confrontational Congressional briefings, CIA interrogators threatened detainee Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri with a power drill and a handgun. While Hayden claimed that the use of anything other than approved techniques was referred to the CIA’s Inspector General and the Justice Department, this incident went unreported. The chief of the CIA base said he assumed the interrogator had received approval from CIA headquarters. He added that he had already received warning from two senior level CIA officers to scale back how much he reported on detention center activity.

The most serious injury resulting from the CIA’s torture program was, in fact, death. On November 20, 2002, Gul Rahman (who was initially not reported to the Senate Committee as being in CIA custody) died of hypothermia in a black site in Afghanistan after being chained to the concrete with no clothing on below his waist. No one in the program was punished, but one of the CIA officers involved was subsequently recommended for a $2,500 cash reward for his “consistently superior work.”