Delhi, April 15 (by cable)

Sunday, March 23, must have been a disturbing day for innocents who believe that there is still such a thing as an unchanging East.

On that morning, Delhi’s hot late-spring sun beat down on both a retiring Viceroy and handsome young Lord Mountbatten, who has inherited the massive sandstone and marble vice-regal palace with instructions to preside over the liquidation of Britain’s Indian Empire.

Late the same afternoon, the sun’s rays, slanting across the broken walls of Delhi’s famed old sixteenth-century fort, fell on the opening of the unofficial, theoretically non-political Asian Relations Conference. Three hundred delegates and observers from all over Asia and 2,000 local visitors were there at the call of India’s world-minded Jawaharlal Nehru to consider the future of their continent.

Both incidents were straws in the freshest breeze that has blown across the expanse of Asia since steam navigation made it a next-door neighbor of Europe. Although their close timing was a coincidence, the two events are strikingly related: Mountbatten’s arrival marked the climax to the vigorous 60-year-old Indian Nationalist movement. India was to have a chance to become independent. Hard-pressed Britain, unready to attempt resubjection of the Crown’s brightest jewel, had agreed to erase the long familiar pink from the Indian section of the Atlas.

The Asian Conference likewise signaled a changing era. It was conceived early in 1946 by Nehru, whose nine terms of political imprisonment have never dimmed his sense of history. After the recent war’s sharp impact on the East he looked around him and saw what he regarded as the final quivers of the Colonial Age. It was time, he argued, for Asians to get together and prepare for the new day at hand.

Memories of Asia’s past glories are thick on the site chosen for the conference. In legend this bit of high ground was the seat of the first Delhi kingdom of Hindu epic times. Millennia later it became the symbol of Mogul might when Emperor Humayun built his fortress city there 400 years ago. Now the still stout walls look down on the British-built city of New Delhi, with its geometric pattern of boulevards, park circles, and officials’ bungalows.

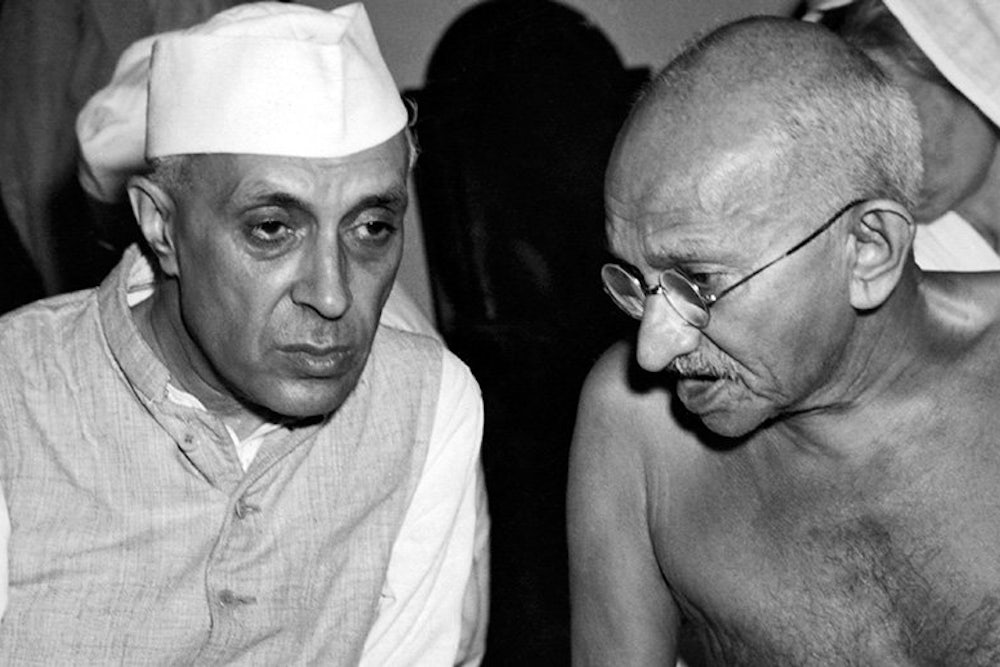

Within a one-mile circuit of these walls, representatives of renascent Asia met in a huge temporary auditorium which had burlap roof and walls. After it was filled to capacity the first day, the walls were let out. For the closing session, when the venerated Gandhi addressed the conference, more than 20,000 visitors stuffed themselves into what the Indians call the pandal, or “big top.”

Leaders of national delegations sat on a streamlined, two-banked, semicircular dais that might have been designed in Hollywood. Behind them a grand-scale continental map (showing Europe as a small appendage in the upper left-hand corner) was lighted by a neon sign flashing “Asia.” Nehru himself key-noted the conference in a carefully worded address.

Speaking of the postwar world, “this watershed which divides two epochs of human history and endeavor,” he said, “This conference in small measure represents the bringing together of countries of Asia. Whatever it may achieve, the mere fact of its taking place is itself of historic significance.”

He also had something a little more definite in mind.

“For too long,” he observed, “we have Asia have been petitioners in Western courts and chancelleries. That story must now belong to the past. We propose to stand on our own feet and to cooperate with all others who are prepared to cooperate with us. We do not intend to be playthings of others.”

A similar temper pervaded the speeches of many delegates. Look at the record they urged; in one generation a seemingly secure colonial world had kicked over its traces. The Middle Eastern countries had asserted their will for self-rule. India had reached the threshold of independence. Burma was about to elect her own constituent assembly. The Indonesian Republic had gained recognition from the Dutch government. The war-devastated Philippines had become independent. Viet Nam had emerged and was struggling for its existence. Yes, and Mongolia had cut adrift from China, while Korea was being extricated from Japanese rule.

Meeting in these circumstances the conference was unique in Asia’s history. It was entirely a continental family affair. Guests met many sorts of Asians but no “Asiatics”—“Asiatic” is a term now resented here as a slightly more derogatory than hobo, bum, or coolie. Among them were professors, revolutionaries, economists, politicians, scientists, members of governments, feminists, high judicial and administrative officials from various countries.

All Asia Came

They had come from the four corners of the continent. Tibetans had walked 21 days over the windy plateau and mountain passes south of Lhasa before they reached the speedier automobiles, trains, and planes of India.

The Viet Nam delegates reported that two squads of their messengers had been killed while smuggling their credentials through from Ho Chi-minh’s beleagued headquarters in Bangkok, where they were waiting. Young, shrewd Indonesian Premier Sutan Sjahrir was brought in an Indian plane chartered for him by Nehru’s government. From Ulan Bator three Mongolian representatives flew to Moscow, where they picked up the Russian interpreter who was to be their only contact with the other delegates. Then they flew on to Baku, Teheran, Karachi, and Delhi.

Delegates and observers also came from Nepal and Bhutan; from Egypt; from the Hebrew University in Palestine and the Arab League; from Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan; from the Soviet Republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Khazakistan, Tadjikistan, Uzbekistan; from Burma, Ceylon, Malaya, Indo-China, Siam and the Philippines; from China and from Korea. No Japanese arrived, although some were invited. The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) still prefers that the Japanese stay home.

With few exceptions, the delegates were not counted among the policy makers of Asia. Some of them were ivory-tower specialists. During their 10 days at the conference they discovered no new truths. But in a series of roundtable discussions generally guided by an inner group of Indian sponsors they thought in international terms and agreed on some of the important things about Asia today. For example, they generally acknowledged that:

1. Asia, anxious for independence from Western imperialism, believes the goal to be so close that successful transfer of power is the most pressing immediate problem.

2. Political freedom without economic independence is meaningless. Control of each country’s agriculture and industry must rest at home, not with foreign interests. Colonial countries are also eager to reduce their dependence on a single crop or product such as rice, rubber, tin, or sugar.

3. Yet Asia can’t stand alone. It must devise arrangements that will attract foreign assistance without giving outside leaders control of domestic economy, thereby reintroducing imperialism in a new guise.

4. Asia is predominantly a continent of impoverished peasants. Raising their standards is the first step required on the road to continental prosperity.

5. Most of Asia is industrially primitive. Outside the Soviet belt and parts of the Near East, only India has any heavy industry. There is no shipping or automobile industry, no manufacturing of transport and communications equipment or of basic defense weapons and supplies.

6. The farmer and industrial worker lives and labors in backward, degrading conditions which require vast improvement. Health, sanitation, housing and education remain at deplorable levels.

7. To make up for such fundamental deficiencies in agriculture, industry, and human living, individual initiative is not enough. Each nation must decide for itself how far the state will intervene. In most countries there is a tendency toward state control of basic industries, defense industries and communications, with close supervision over other nation-building activities but (except in the Soviet zone) with considerable room left for private enterprise.

8. Much of the required finance, capital, equipment and trained management for the reconstruction of Asia must be found outside the continent. Asia’s accumulated exchange credits and normal exports of primary goods won’t pay the bill. Borrowing from abroad will be necessary, therefore, to finance rehabilitation programs. Transactions of this sort should conform to United Nations standards and avoid infringement of the sovereignty of any Asian nation.

9. Asia must wholeheartedly support the United Nations to preserve peace. Asia itself can be a stabilizing factor in a world suffering from atomic jitters.

10. At the same time, Asian nations should give whatever help possible to Asia freedom movements. They should deny to non-Asian powers attempting to suppress such movements all assistance in matters like docking, airfield facilities or military supplies.

The sum total of the situation, as these delegates saw it, is that the time has come for Asia to make a declaration of independence, but that the continent needs close ties and great assistance from outside to improve its primitive conditions. “We want no ‘Asia for the Asiatics,’” one delegate declared. “The Japanese were wrong there.” At the end the conference voted to carry on its work through a permanent Asian Relations Organization. No constitution was drafted, but it was agreed that the organization should be unofficial and should operate through national units of the same character. The main purpose would be to facilitate contacts between Asian nations at cultural, economic, and possibly political levels.

For the first president of the provisional general council, delegates again turned to the man who inspired the conference, Jawaharlal Nehru.

A Minimum of Explosions

Few conferences accomplish exactly what they set out to do. Devising ways and means to keep this one under control despite explosive subjects on the agenda was a chore that had kept the Indian Planning Committee worrying nights. To reduce risks of splits between delegations, they decided that the conference should pass no resolutions and commit itself to no fixed views. They ruled that no country’s internal problems should be discussed.

Several issues were glossed over. No one raised the question of Communist influence in Asian countries. Nor did anyone suggest that conference of this sort should consider machinery to deal with disputes between Asian states.

Among various delegations, the Soviets attracted some attention; despite fear of communism in many circles, there is a latent respect in Asia for the apparent all-around progress made by the Soviet countries in one generation. But even making allowances for the language barrier, one delegate observed, “It is hard to get to know them. They have come here and seem interested in discussions. But, except for cultural topics, they regularly tell us they have already solved all problems that are facing the rest of us and conversation stops there.”

An active Chinese delegation, spark-plugged by George Yeh of the Foreign Office, showed itself particularly vigilant over references to the place of Chinese residents in Southeast Asian countries to which the Chinese have migrated in large numbers. As representatives of the largest country, the Chinese, who have their own ideas about leadership of Asia, invited the conference to hold its next general session in China in 1949.

In an atmosphere that was unquestionably charged with distrust of imperialism and of imperialist nations, Filipino delegates threw a surprise. Replying in press conferences and public statements to oblique references to the United States, the group declared in the unofficial words of Anastacio De Castro, its leader, that “talk of American imperialism in Philippines now is bunk.”

Politics and Parties

Throughout the conference the emphasis was on the India-China colonial belt region. Several Southeast Asian delegations came with specific missions. Indonesians, for example, frankly bid for trade and diplomatic relations with other countries, while the struggling Viet Namese begged for help from any quarter in their resistance to French pressure.

By the time the 77-year-old Gandhi, who had come from riot-torn Bihar Province, mounted the rostrum at the final session to tell the Asian countries to love their neighbors, delegates had completed a busy 10 days absorbing politics, economics, culture and the fruits of a social whirl that outshone even the usual spectacles of this party-minded national capital. The new Viceroy held a reception for the entire conference. On the same evening a thousand people filled the compound of Nehru’s official bungalow to see the Orissa masked dancers. Indian maharajas, prominent individuals, foreign consular and diplomatic officers arranged teas and cocktail parties. “I have been to three today, and there are two more after this one,” one weary delegate said across a tea table on about the eighth day. “And at every one I meet the same people.”

If the Indians played a leading role in the Asian Conference, it was partly because theirs was the host country, and partly because they believe they have a big destiny in Asia, and partly because the Indian Nationalist movement got a generation’s head start on some other colonial countries. Most of the top leaders of India are now grandfathers. But the conference demonstrated that Asia has a crop of young leaders as well. Sjahrir of Indonesia is in his mid-thirties, for example, and Aung San of Burma, who could not attend because his party was campaigning (very successfully) in the National Constituent Assembly elections, is even younger.

As many as a dozen languages were used in the conference. But one thing these Asians discovered about themselves is that they have just one medium of international communication—the English tongue. Countries from the Mediterranean to the China Sea sent delegates who spoke English; all other languages, even the old court tongues of French and Persian, merely proved of regional importance. Some support developed for encouragement of a constructed language such as Esperanto, but most delegates, including the Georgian, agreed that English is the sole contender as the international language of Asia.

In this frankly exploratory conference many frayed and tangled threads of present-day Asian life found a chance to come together. Whether they will successfully form the warp and woof of a real continental fabric will be revealed by the progress of the new Asian Relations Organization.