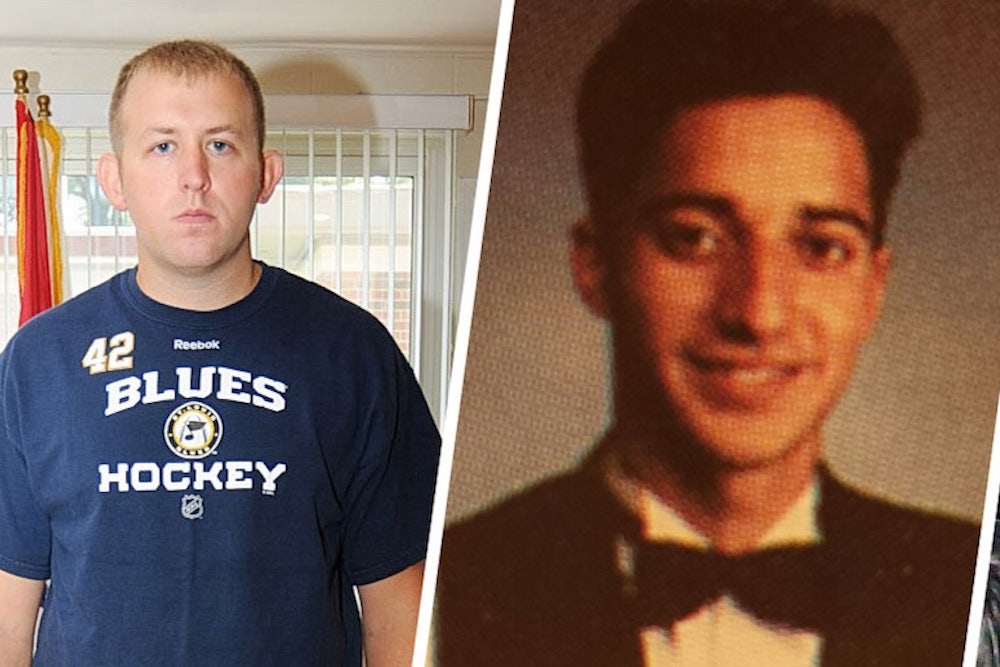

Our expectation that memory is consistent and reliable is ubiquitous. It is taken for granted in day-to-day interactions and determines countless decisions. We do not acknowledge often enough how unstable our memories are, how susceptible they are to change, and how serious the implications of those changes are when we rely on memory to determine the fates of real human beings. In this way, memory provides a lens through which to view the release of former Ferguson officer Darren Wilson’s testimony of how and why he shot Michael Brown, the deterioration of Rolling Stone’s story, and the popularity of the Serial podcast.

This has been underlined by recent events. The image of Michael Brown being shot with his hands up has become a protest meme. But it's an image in our minds alone: While some (not all) witnesses described the shooting this way, we have no video or photographic evidence. In his grand jury testimony, Wilson did not deny that the gesture happened, but he interpreted it differently: “The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked. He comes back towards me again with his hands up.” Wilson also described Brown as “Hulk Hogan” and “like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots.” If Wilson told the truth as he remembers it, then needless to say, he felt threatened when he shot Brown.

But it’s possible that every time Wilson recalled shooting Brown, his memory changed in small ways. He must have known immediately that he would need to explain why he used force on Brown. Whether consciously or not, Wilson might have remembered Brown as more threatening each time he recalled the shooting.

A memory’s potential to change each time it is recalled was discovered by Dr. Karim Nader in 2000, when he argued that “[memory] consolidation is not a one-time event, but instead is reiterated with subsequent activation of the memories.” Since then, Nader and others studying memory and neuroscience have also discovered that false memories can be implanted, and traumatic memories can be erased. While we don’t know how often these tricks of memory can occur in a person’s day-to-day life, we occasionally see them acknowledged in the way personal accounts are framed.

In a piece about the UVA rape story by Slate's Hanna Rosin, she writes of Jackie, the woman whose personal account Rolling Stone published without interviewing the accused, too: “It’s possible she was so traumatized that she is getting a lot of the details wrong, or that whatever happened to her has taken on greater levels of baroque horror in her imagination.”

And Serial, the wildly popular This American Life spin-off about a convicted murderer whose guilt is anything but assured, kicks off with a disclaimer about memory. Before Serial’s narrator, Sarah Koenig, even outlines the show’s central murder mystery for the first time, she explains something else. “Before I get into why I've been doing this,” she says, “I just want to point out something I'd never really thought about before I started working on this story. And that is, it's really hard to account for your time—in a detailed way, I mean.”

We’re aware that memory is not definitive, and yet our culture and our judicial system continue to put enormous emphasis on it. Wilson’s account played a significant role in the grand jury's decision not to indict him. Jackie's remembered account was presented as fact by Rolling Stone's seasoned editorial team. Serial’s Adnan Syed is serving a life sentence largely based on the account of one person who claimed to have helped Syed bury the victim's body—and that Syed couldn’t remember his alibi. He claims to have no memory of where exactly he was when his ex-girlfriend was murdered, presumably because that window of time didn’t have any particular significance until after her body was found.

In the 15 years since Dr. Nader began his investigation into the neurological processes that underpin our experience of memory (and, incidentally, since the murder in Serial occurred), there has been a significant increase in how much of our lives are documented. We create massive archives of our correspondences daily using email and messaging services, like texts, Gchat, and Facebook messenger. We also publicize our whereabouts and who we spend our time with on social media. Digital security cameras and surveillance systems have become more capable and more common. Most cell phones now have high-quality cameras.

While we are almost certainly compromising our privacy, we may also be liberating ourselves from our stubborn reliance on memory when convicting people of crimes. Earlier this month, the White House announced that it would seek $75 million from Congress to fund 50,000 body-worn cameras for police. Programs like this may finally liberate our judicial system from the biases of memory. Whether they will improve criminal justice, though, is another question.