Eighteen miles west of Knoxville lies the town of Oak Ridge, birthplace of the atomic bomb. We drove over a recently constructed road and I asked the driver, a young private, when the road was built and how far it extended. He smiled obligingly, hesitated and finally said: “Suppose it’s perfectly all right to tell you, but I wish you’d inquire about it from the proper authorities when we get to Oak Ridge.”

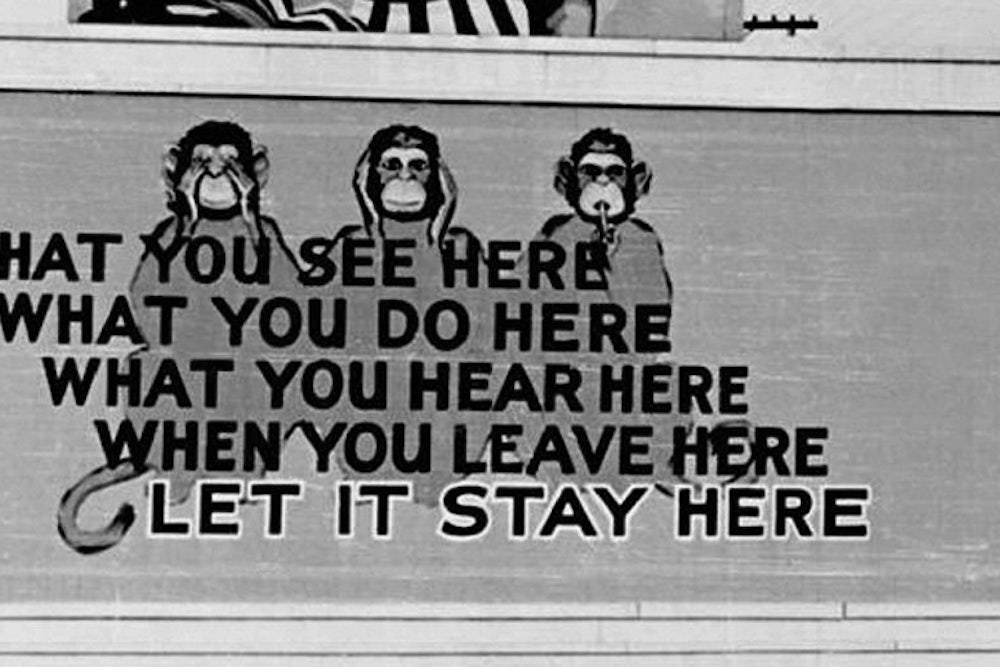

That was my first lesson in what is a habit of long standing with Oak Ridgers: security. I found out that security includes not only the Clinch River and Cumberland Mountains which keep the outside world from this atomic city. I saw gates within gates and barbed wire fences and signs warning of “Prohibited Zones” and “Restricted Areas.” And posters in dormitories, offices and stores: “Protect Project Information….”

People in authority say, “Don’t quote me on this” or “This is off the record.”

A young scientist told me, “Even those who talked in their sleep learned to keep their mouths shut.” I asked naively wherein lay the danger of talking in one’s sleep, and the reply was: “What if the wife heard you?” Things aren’t so bad now, he said with relief. “There was a time, coming home from the lab, when I couldn’t talk to my wife at all. I pretty well knew what the Project was making, but I couldn’t tell you. We’d sit around the dinner table and the strain was terrible. A man could bust. Then we started quarreling. Over nothing, really. So we decided to have a baby.”

A psychiatrist at the Oak Ridge Hospital told me of his increased work load during the days before the Bomb was dropped. “The strain was terrible,” he said. “I had my hands full. But practically no one talked. One fellow couldn’t stand it, so he told his wife. But she felt the secret was too much for her and she told it to a friend. So they had to terminate all three of them in a hurry.”

Actually very few of the 75,000 Oak Ridgers knew what was being done on this great reservation. Some rumors had it that synthetic rubber was being made. Wiseacres said they were getting ready to manufacture buttons for the Fourth Term. One plant didn’t know what the other was doing, and even within plants the work was completely departmentalized. The people on top knew, the scientists knew, but they didn’t talk. The Bomb hit Hiroshima and the Oak Ridge Journal ran a banner head: “Oak Ridge Attacks Japan.”

But the people still don’t talk. The whole world knows what Oak Ridge is producing. What isn’t known is how it’s being produced. As an outsider you will be heard out with tolerant suspicion when you talk of atomic fission or the Bomb, but if you mention plutonium or U-235, the cold stares set in. The more polite Ridger will listen to your question, dig in his pocket for the Smyth Report, and pointing to a well worn page, will say: “There is your answer.”

The fact of the matter is, the Smyth Report contains more information about the Bomb than most people in this town possess. The ones who knew more keep it to themselves, and the rest feel it’s none of your business.

At first glance you wonder what all these thousands of people from all parts of the United States are doing in this hidden Tennessee country. From the ridges which lace the reservation in all directions, you look in vain for signs of industrial activity. Finally you discover several smokestacks. But they are smokeless. All over the place, seemingly planless at first, are a jumble of hutments, barracks, dormitories, trailer camps. Perched on the ridges are the demountables on stilts looking like chicken coops, the houses and permanent apartments. The overall impression is a combination of army base, boomtown, construction camp, summer resort. The “Colored Hutment” section looks like an Emergency Housing Slum Area.

I asked my driver, a young woman from this Bible Belt country, where the plants were. “We’ll git to ‘em,” she said with a knowing smile. “It takes time.” And like a trained guide she pointed to the neighborhoods and called them off: “Where you’re staying, that’s Jackson Square, main residential and business section.” I scribbled in my notebook: Pine Valley, Elm Grove, Grove Center, Jefferson Center, Middletown, Happy Valley. While pointing out the neighborhoods, she also suggested that I jot down the A&P’s, the Farmers’ Markets, Supermarkets, and a hot dog stand selling Coney Island dogs for ten cents. She called my attention to the fact that in the Trailer Camps the streets were named after animals: Squirrel, Terrier, Raccoon. But I didn’t ask her how come there was a Lincoln Road in the heart of Tennessee.

“I want you-all to write a good story about Oak Ridge,” she said warningly. “There’s been many of you writers from the North, but I ain’t seen a good story yet. You fellas don’t seem to git the sperit of this place.” I heard a great deal more on the subject of “the spirit” from articulate residents during my stay.

“There’s 53 old cemeteries here,” my informant continued, “spread over the 95,000 acres of Roane an’ Anderson Counties. When the people was moved off the land for the Project to commence, the Army promised it would take care of the cemeteries. And they do.” On Decoration Day the approximately 3,000 former inhabitants of these ridges are all granted passes to come and decorate the graves. “What happens when somebody on the Project dies?” I asked. “Well,” my driver said, “they’s shipped back home where they’s from.” What’s more, she added, few people ever die here, because most of the workers are young. “I never seen a grandmother in two years I been here,” she said.

The plants are widely dispersed and hidden in the valleys. Miles of wooded areas separate them from one another and from the residential districts. Mountains and ridges prevent any observation until you are actually near them. First come the warning signs, then the big fences and guard towers, and in the background are the massive atomic fortresses. Again there are no smokestacks, and no smoke pours out. I said to my guide it didn’t seem to me as if anything were going on inside those plants. “Plenty going on,” she replied, “just ain’t no smoke to it.”

The mystery deepened even more with the realization that while a great many things entered the huge structures, very little seemed to come out. Later I learned that it required big quantities of ore and many complicated processes—done here and elsewhere—finally to isolate the negligible bit of precious uranium from the mixture of U-235 and U-238.

There are several methods of extracting the uranium. The Tennessee Eastman plant, known as Y-12, and comprising 270 buildings, uses the electro-magnetic process. Carbide and Carbon Corporation, K-25, occupying 71 buildings, obtains the same results by gaseous diffusion. S-50, operated by the Fercleve Corporation, employs the thermal-diffusion method. All these processes have been tested, and they all work. X-10, the Clinton Laboratories, formerly connected with DuPont, are doing research on plutonium, the main plant being at the Hanford Engineering Works in the State of Washington.

Three shifts keep the plants in operation day and night, and thousands of workers and technicians from Oak Ridge and its environs check in past the maze of fences, guards and more guards. Few of them ever see the finished product, and before the Bomb struck Hiroshima they hadn’t the least inkling of what was going on behind the thick walls that separated them from the radioactive uranium. Charlie Chaplin’s awe at entering the super-modern factory in “Modern Times” was nothing compared to what the Project workers first experienced in the plants. Charlie at least saw what he was making. The Ridgers still can’t see, but they know. There’s a purpose to all the button-pushing and fantastic equipment.

“I still don’t see how a gadget can take the place of a brain,” a worker said philosophically,” but leave it to them long-hairs to think things out.”

Three years ago the Manhattan Engineer District was a plan. The Black Oak Ridge country was chosen as one of the three atomic sites for its electric power, supplied by the TVA, its inaccessibility to enemy attacks, its water supply and the then uncritical labor area. The small farmers who inhabited these ridges were moved off the land with proper remuneration and dispatch. They could not be told why.

The bulldozers moved in, and with them arrived the jeeps and automobiles. The army, having the scientists in mind at first, built several hundred permanent houses and put fireplaces in them. Often the fireplaces were there before the walls were up. Then the plans were changed, and more houses were built. More workers arrived, and the need for shelter became acute. They started building barracks, hutments and the TVA came to the rescue with those square, matchbox demountables. And finally the trailers were brought in and set up below the ridges.

It was not an inspired migration. Many were lured by high wages; others by promises of comfortable living. The scientists, those who had worked with the Project in other parts of the country, knew the reasons. The GI’s came because they were told to come. One woman said it was a good way of getting rid of her husband. “I knew he couldn’t follow me past the gates.”

They waded in the red-clay mud, and some walked about barefoot for fear of losing their shoes. The clay was hard and they had to water it at night in order to dig it next morning. People knew there was no gold to be found in the Cumberlands, and therefore it is the more remarkable that they worked with such fervor and pioneering zeal.

When Oak Ridge had 15,000 inhabitants, there was only one grocery store in town. Businessmen, unable to find out the potential number of customers or clients, were reluctant to move in. One five-and-ten concern asked for a contract barring competitors for a period of ten years. Slowly, warily, entrepreneurs set up shop in Oak Ridge. And they’ve done quite well by themselves, so well, in fact, that the OPA has had to step in on occasion to curb some enterprising souls.

Roads were laid out, buses started to operate, taxi-cabs were brought in. Neon lights went up on business establishments, and some people started calling Oak Ridge “home.” They cut weeds and planted Victory gardens and raised pets. People started having children, many children. “Pretty near all there was to do in those days,” a father said.

Today the city has its Boosters and Junior Chamber of Commerce, and a Women’s Club. It has beauticians; one hair stylist advertises as being connected “formerly [with] Helena Rubinstein’s Fifth Avenue, NY.” There are tennis and handball courts. A symphony orchestra, composed of Project employees, is led by a prominent scientist. There are seven recreation halls into which people can wander and join a bridge game or participate in community singing. There are several movie houses and a Little Theater and a high school. But Oak Ridge still has no sidewalks. “When I first came here,” a youngster of ten said, “I missed sidewalks most. Now I don’t care.”

Some people point with pride. Others point at “Colored Hutments,” where living facilities are primitive, to say the least, though comparable to some of the housing for white workmen. Negro children are not permitted to go to school with whites; they journey to nearby Clinton for their education. And for that reason many Negroes did not bring their children to Oak Ridge. Plans are now being made to provide school facilities for the Negroes as soon as a sufficient number of children are enrolled to justify it. They have one recreation hall, the Atom Club, and one movie house, which is located 12 miles from their hutments, in the K-25 area.

The GI scientists point to the great discrepancy in salaries.

No one points at the food served at Oak Ridge cafeterias, and that’s as it should be.

One of the town’s most interesting institutions is the Oak Ridge Hospital. It is an experiment in what its brilliant young director, a lieutenant colonel, says “has absolutely no relationship with socialized medicine.” He calls it “The Group Insurance Plan.” Nevertheless, I advise Dr. Fishbein not to be lulled by the colonel’s reassurances. The plan works something like this: each family head pays $4 a month, and the medical services include all his children below the age of 19. Doctors make private calls, but the fees go to the hospital. There is no private practice. The hospital has 300 beds and can handle 1,500 in-patients monthly. Five psychiatrists are attached to the institution, and their emphasis is on what they call group therapy. The hospital is staffed with high-caliber practitioners, many of them from the Mayo Clinic. Everybody in Oak Ridge can afford to enjoy good health.

This is the only city in the United States which has no unemployment and no reconversion problem. There are no election headaches, since the councilmen act only in an advisory capacity to the District Engineer, who is both an army officer and the mayor. Those who acquire an additional child try to move from a B-house to a C-house, and so on up to a F-house, which rents for $73 a month. And those who marry and are lucky move from their “Single” dormitories to an A-house. But no matter where they move, most of it is Cemesto (cement and asbestos rolled into sheets). And there’s a feeling of temporariness about the whole place. The one bank in town is bulging with assets, for which the state of Tennessee is not ungrateful. The inhabitants of Knoxville have learned to tolerate the outsiders, if not for their ways, for the revenue they’ve brought.

There is a tendency among many to talk about the “past” and about “the spirit” they had “in those days.” A few have left for the other “home,” but most are waiting. The Bomb that pulverized Hiroshima was the reason for their existence. The world was shaken to its very foundations. Now the people who’ve unchained this fury are thinking of its implications not only for their immediate tomorrow, but for the world’s also.