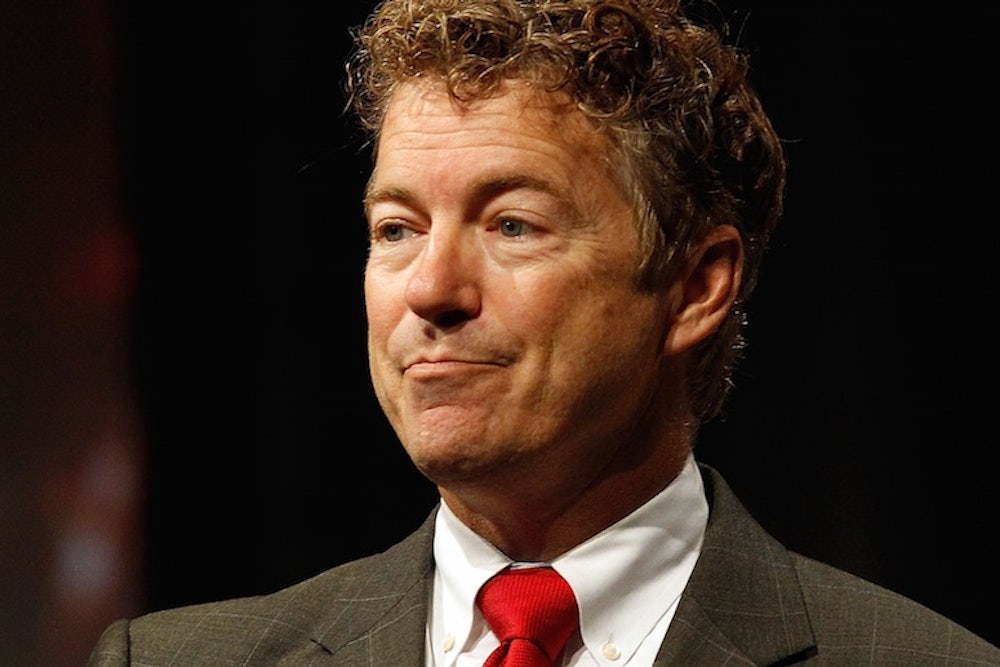

On Wednesday, Senator Rand Paul introduced a “Declaration of War” against the Islamic State. The measure says that a “state of war exists between the organization referring to itself as the Islamic State (ISIS) and the government and people of the United States.” The legislation has next to no chance of passing, but Paul is using it as a political stunt to portray himself at a conservative who will uphold the true meaning of the Constitution.

The Islamic State (IS) has desperately tried to portray itself as a legitimate state—by doing everything from collecting taxes to issuing passports to printing currency—and Paul’s move only bolsters their case. A Declaration of War would confer a great deal of legitimacy on IS not as a terrorist group or barbaric band of thugs, but an enemy state.

Paul’s measure runs counter to the position taken by the international community, which has sought to delegitimize IS. President Barack Obama has stated the U.S. position: “ISIL is certainly not a state. It was formerly Al Qaeda’s affiliate in Iraq, and has taken advantage of sectarian strife and Syria’s civil war to gain territory on both sides of the Iraq-Syrian border. It is recognized by no government, nor by the people it subjugates. ISIL is a terrorist organization, pure and simple." The French foreign minister has refused to even use the terms IS, ISIS, or ISIL because it confers too much legitimacy on them, instead calling them "Daesh cutthroats."

Declarations of War are reserved for use between enemy states, and America's founders did not think that a formal declaration would be necessary for every conflict. Alexander Hamilton noted in Federalist 25 that “the ceremony of a formal denunciation of war has of late fallen into disuse." International law only recognized the declaration of war as something necessary for warning another state of a conflict. The 1907 Hague Convention stated in Article 1: “The Contracting Powers recognize that hostilities between themselves must not commence without previous and explicit warning, in the form of a reasoned declaration of war or an ultimatum with conditional declaration of war.” Frederic Baumgartener, a historian of declarations of war, noted that “the state declaring war must provide to the world community an explanation of the causes that provoked the war.” Declarations of War have fallen out of favor since the middle of last century: As University of Virginia law professor Robert F. Turner, an expert on war powers, notes, “No country has clearly issued a declaration of war since the UN Charter went into force in 1945."

The Unites States has used declarations of war for rogue actors. Even in the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln did not go to Congress because the south was not considered a foreign state. Chief Justice William Rehnquist later wrote that, “there was of course no declaration of war by the Union, because it did not recognize the Confederacy as a separate nation.” Instead, Lincoln issued a proclamation on April 15, 1861, in which he described mobilization against “combinations too powerful to be suppressed.” When the United States has used force against pirates in the First Barbary War in Tripoli and the Second Barbary War in Algiers, the president received authorization from Congress but did not obtain a declaration of war. In the legal community, the idea that the United States should issue Declarations of War against non-state actors such as terrorists has become a fringe position and, as professors Jack Goldsmith and Cutis Bradley note, “almost no one argues today that Congress’s authorization must take the form of a declaration of war.” The reality is, “the United States has been involved in hundreds of military conflicts that have not involved declarations of war.”

Professor Mary O’Connell of Notre Dame Law School has argued that in counter-terrorism, “Declaring the struggle against them ‘war’ elevates their status of above that of mere criminals.” Similarly, Judge Christopher Greenwood of the International Court of Justice has noted that “in the language of international law there is no basis for speaking of a war on Al-Qaeda or any other terrorist group, for such a group cannot be a belligerent, it is merely a band of criminals, and to treat it as anything else risks distorting the law while giving that group a status which to some implies a degree of legitimacy.”

To make his case, Rand Paul states in his resolution that "the organization referring to itself as the Islamic State has declared war on the United States and its allies." In doing so, the Kentucky senator has fallen into ISIS' trap: Their declaration of war is a propaganda tool designed to trick nations into responding with similar declarations, thus bolstering ISIS' legitimacy. To declare war on this motley crew of terrorists, at a time when the international community is trying to delegitimize them and stem the flow of foreign fighters to the region, is nothing short of reckless.

If Paul's declaration of war is an attempt to define himself as a plausible presidential candidate who's competent in foreign policy, it has accomplished precisely the opposite.