This is the story of the last 17 days of the Nixon presidency insofar as I have been able to learn the story. There have been many such accounts. Most of them, including some that pretended to be but in the main were not obtained the White House, originated in Congress and in other peripheral quarters. The most to be said for this account, apart from statements attributed to members of Congress, is that it reflects and is confined to what I was told at the White House by officials who were involved, some intimately and some at varying distances, in the agonies of discussion and maneuver that preceded and accompanied the first resignation of a President of the United States and the first accession to the office of a President who had not been elected to either it or the vice presidency.

We must start again, as I did in my account in this journal’s August 10 & 17 issue of the President’s final approach to judgment, with events in Washington and San Clemente on July 24. The U.S. Supreme Court on that day announced its unanimous decision that President Nixon must surrender to federal Judge John Sirica, for passing after review and removal of irrelevant material to Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski, the tapes and any other records of 64 White House conversations that might bear upon the guilt or innocence of defendants in a Watergate case. The President was at his Western White House and residence in San Clemente. Eight hours elapsed between the announcement of the decision and the announcement by Mr. Nixon’s chief Watergate attorney, James D. St. Clair, that the President intended “to comply with that decision in all respects.” It was explained then that it took time to absorb the nuances of so important and complex a decision and that the President and his chief assistant, Gen. Alexander Haig, needed and were taking time to solicit advice from people in Washington and elsewhere, not on whether to comply but on how best to announce the intention. Since then I’ve learned that the uses of the intervening eight hours were more murky and interesting than the previous account indicated and, in a way about to be noted, were fatefully indicative of what was soon to come.

One of the options suggested to the President, and rejected by him, was that he announce that he was defying the Supreme Court decision for the good and protection of the presidency and of future Presidents, publicly destroy all the remaining White House tapes, and then resign. This suggestion came from a long-time adviser to Republican Presidents, including Mr. Nixon and now President Ford—an adviser who is widely regarded by journalists as a moderate and a moderating influence. Mr. Nixon might have welcomed and paid serious attention to such a suggestion if a far more critical and immediate matter had not been on his mind that day in San Clemente. It was what to do about the ruinous passages that he knew and had known since at least early May to be on three of the taped recordings that Judge Sirica and now the Supreme Court had ordered him to surrender, through the judge, to Jaworski. They were portions, amounting to a total of some six minutes, in 129 minutes of three conversations with H.R. Haldeman on June 23, 1972. That was six days after the original break-in and arrests at the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate office building in Washington and nine months before March 21, 1973, when Mr. Nixon had said again and again that he first learned of efforts at the White House and at its election-year adjunct, the Committee for the Reelection of the President, to conceal or, in the tag phrase that has joined the national language, to “cover up” White House involvement in the Watergate crime. Because he had listened to the recordings on May 5 and 6, he knew that they proved he not only knew about the attempt to cover-up but participated in and authorized a key part of it on June 23, 1972.

Here I combine fact with conjecture. The fact is that J. Fred Buzhardt, the President’s staff counsel in Washington, called for the June 23 recordings as soon as the Supreme Court decision was announced and spent the rest of last July 24 listening to them in his office in the Executive Office Building next door to the White House in Washington. Why did he go immediately to those particular tapes? “That is something I will never tell you,” Buzhardt told an inquirer. My conjecture, supported to some extent by the impression of other White House assistants, is that Mr. Nixon ordered Buzhardt to review the June 23 tapes and tell him, the President, whether in Buzhardt’s opinion they were as damaging as the President feared they were.

Buzhardt reported within hours to the San Clemente White House that he had listened to the tapes and that the Watergate passages would finish the President. In terms of strict and limited legalities, Buzhardt said, they did not necessarily destroy the President’s defense. In the political and human terms that concerned the country and the House Judiciary Committee, then moving toward its first impeachment votes, the taped passages were ruinous because they proved Richard Nixon to be a liar and an early participant in decisions that had led to the indictment of former Attorney General John Mitchell, H.R. Haldeman, and five other Nixon men. The President, Haig, and St. Clair knew that this was Buzhardt’s opinion of the June 23 tapes when St. Clair announced Mr. Nixon’s decision to comply with the Supreme Court decision. They knew it when, during the four remaining days of Mr. Nixon’s last stay as President in California, Communications Director Ken Clawson and Press Secretary Ronald Ziegler raised the White House counterattack upon the House Judiciary Committee to a peak of irrational and, as it turned out, self-defeating frenzy. They knew it only July 27 when, after the committee had voted the first article of impeachment, Ziegler said in a written statement: “The President remains confident that the full House will recognize that there simply is not the evidence to support this or any other article of impeachment and will not vote to impeach. He is confident because he knows he has committed no impeachable offense.” Did Ziegler know about the June 23 tapes and Buzhardt’s estimate of them when he said this for the President? The available answer throws an explanatory light on the Nixon White House at its top and center in the final days. Ziegler and Haig, remember, were then and for many months had been the President’s only regular and intimate official confidants. They were assumed to work in concert. On the 27th and later, until and after Mr. Nixon’s resignation, Ziegler hid from reporters and refused to answer questions. It was said later and authoritatively that Haig didn’t know whether Ziegler knew of the tapes and Buzhardt’s report. Haig knew only that he hadn’t told Ziegler. Haig didn’t know whether Mr. Nixon had told Ziegler.

The Nixon party returned to Washington July 28. The peddled and generally reported story thereafter was that knowledge of the damaging passages came as a terrific shock to Haig and St. Clair when rough, partial transcripts were given them on July 31. Here again the fuller facts tell much about the Nixon White House in its death throes. St. Clair heard the key passages on July 30 and perceived that Buzhardt had, if anything, understated the damage. Buzhardt, who until then was Haig’s only authority for what was on the tapes, stood low in Haig’s judgment because of some fairly serious mistakes in the handling of subpoenas and tapes last year. Haig had laid down a rigid rule that transcripts be made only from copies of original tapes, in the sensible apprehension that the originals might be harmed during transcription. But Haig’s opinion of Buzhardt and the time required for copying tapes did not entirely explain the slow dissemination of the bad news to and at the top of the Nixon staff. Only a realization by the President and Haig of the devastating effects that the Watergate passages were bound to have upon everyone who became aware of them could explain it. Henry Kissinger was told on the 31st that bad trouble was in the tapes, but he didn’t know what the trouble was and how bad it was until the June 23 transcripts were published late on August 5. Communications Director Clawson was vaguely alerted on August 2 but he, like Kissinger, didn’t get the whole score until Haig imparted it to the White House staff just before the transcripts and an accompanying Nixon statement were issued.

Three “defense teams” of lawyers and White House staff writers had been put together after the return from California to deal with each of the three articles of impeachment voted by the Judiciary Committee. Raymond Price, the writer most esteemed by Mr. Nixon, headed one of these teams. Charles Lichstenstein, an assistant to counselor Dean Burch, headed one. Patrick Buchanan, a conservative consultant to the President, and David Gergen, nominally the chief Nixon writer, each thought that he headed the third team. Price learned on Thursday night, August 1, and Buchanan on Friday, August 2, that they might as well forget the defense operations, and they did. Gergen sensed but was never told that he might as well forget it too. Price was shown the Watergate portions of the June 23 transcripts that Thursday night and was told by Haig to begin thinking about a Nixon statement to accompany publication of the transcripts. Buchanan was shown the Watergate portions and given similar instructions Friday. Haig on Saturday, August 3, instructed Ziegler, Price, Buchanan, and St. Clair to prepare to accompany him to Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Maryland mountains near Washington, on Sunday, for a conference with the President. Mr. Nixon was already there with his wife, his two daughters and their husbands, and Charles G. Rebozo, his Florida friend, and companion in trouble.

Masses of tosh have been printed about the Camp David meeting. One of the few points worth making about it now is that the President didn’t have to be persuaded at that stage to publish the June 23 transcripts and acknowledge, as he did the following day, that he’d been at fault in withholding vital information from his lawyers, his congressional defenders, and his staff. The sole issue in substantial doubt and discussion was whether he should leave the way open for early resignation, which he resisted doing but finally did, or commit himself to see the impeachment process through to Senate trial and predictable conviction, which he preferred to do and, after waverings that continued well into the following Wednesday night, didn’t do. I have talked with three of the five participants in the Camp David meeting. None of the three thought it odd, all thought it perfectly natural, that President Nixon conferred in person only with Haig and Ziegler and met them separately, never together.

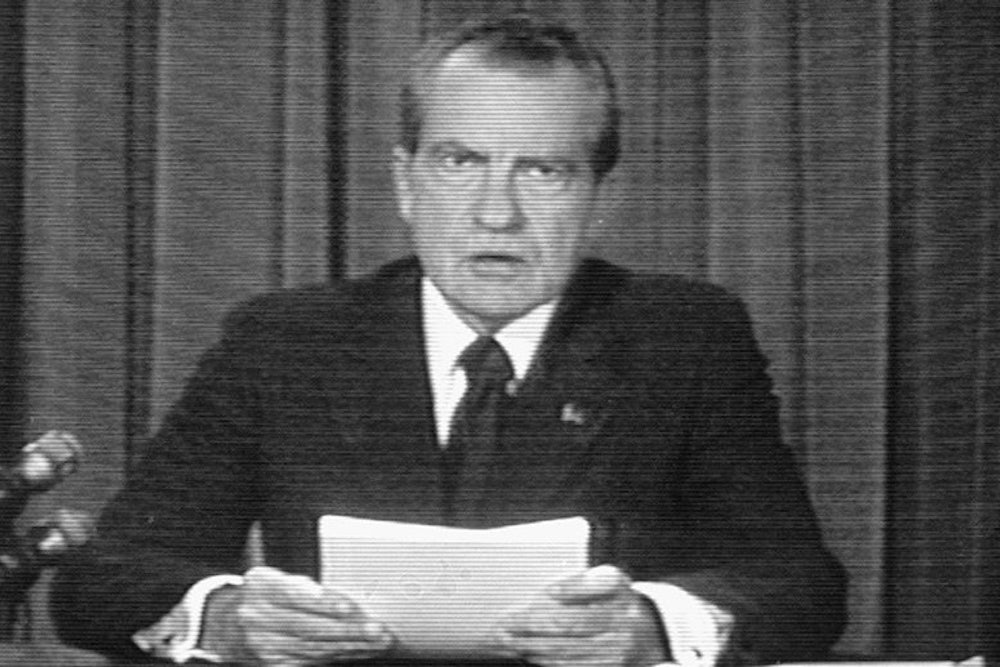

Haig told Price on Tuesday night to begin drafting the resignation speech that the President delivered on Thursday night, August 8. The instructions to Price from the President through Haig never changed. The key instruction was to admit nothing more than a few “mistakes of judgment” and to avoid even the mild acknowledgement of guilt that had appeared in the Monday statement. Price discussed successive drafts with the President by telephone several times and once in person on the last Thursday morning. He never had the slightest intimation that the President might change his mind and refuse to resign. Mr. Nixon nearly changed several times and actually did once, in mid-afternoon of Wednesday before Haig had Sens. Goldwater and Scott and Rep. Rhodes visit him and tell him how hopeless his situation in Congress was. Henry Kissinger, leaving Mr. Nixon at midnight Wednesday after assuring him for 2 ½ hours that he was right in believing that common sense and the international weal required resignation, but never demanding or explicitly recommending resignation, was not altogether certain on Thursday morning that the President would do what he did that night.

Thank God, he’s gone. I’ll miss him and I wish for him the mercy that he doesn’t deserve and probably won’t get.