Tina Frundt was only nine when her foster parents sold her for sex for the first time. At 13, she became friends with a man who convinced her to run away with him from Chicago to Ohio. He then trafficked her all over the U.S. in states such as Iowa, Arkansas, and Atlanta, according to Frundt. At 15, she was back in Chicago when police arrested her on the street, charged her with prostitution, and sent her to a juvenile detention center in Cook County, Illinois.

“I’m a survivor, and I was in the life from nine years old to my mid-twenties,” said Frundt, 40, the founder of Courtney’s House in Washington, D.C. “Back then, there weren’t any laws and I got charged with prostitution.”

Things have not changed much since. Across much of America, underage sex trafficking victims are treated as criminals rather than victims, and law enforcement, lacking training and options, often sends them to juvenile detention centers. That includes D.C., which is why Frundt lobbied for the passage of the Trafficking of Minors Prevention Amendment Act (TMPAA), which the D.C. Council unanimously approved on Tuesday. The law will create immunity from prosecution for minors engaged in prostitution in the District, and require police officers to: refer children "to appropriate services consistent with the minor's status as a victim of human trafficking"; report "critically missing children" to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC); and receive human trafficking training.

The average age at which childen are sold into sex trafficking is 11 to 14, according to the FBI. These children often come from unstable homes; they're foster children, runaways, undocumented immigrants, victims of domestic violence, and LGBT youth. No one knows exactly how many minors are trafficked in America or how many are arrested by authorities. In 2012, the most recent year for which data is available, 136 male and 443 female victims were reported to the federal government as having been arrested as minors engaging in prostitution, according to a Department of State report published in June. But that number isn't even close to reality, as most cases aren't reported to the government, largely because a lot of victims are instead put on probation or held for a different charge. Generally, anti-trafficking groups use missing children statistics to estimate the number of trafficked youth. According to Robert Lowery Jr., vice president of the missing children division of the NCMEC, in the last five years 80 percent of all missing children were runaway children and one in seven runaways were child sex trafficking victims. Of these victims, he adds, 67 percent were in foster care.

NCME acknowledges the difficulty in quantifying the scope of the problem, but estimates that about 100,000 children are trafficked in the U.S. every year, while Innocents at Risk estimates it's closer to 300,000 (the U.S. Department of Justice estimates that 300,000 children are "at risk for sexual exploitation each year in the United States"). Trafficked minors are, of course, just one component—albeit a significant one—of the broader underground sex trafficking economy in America. The State Department report estimated the total sex-trafficking business in eight U.S. major cities in 2012 to range from $39.9 million (Denver) to $290 million (Atlanta) in 2012, with D.C.'s around $100 million.

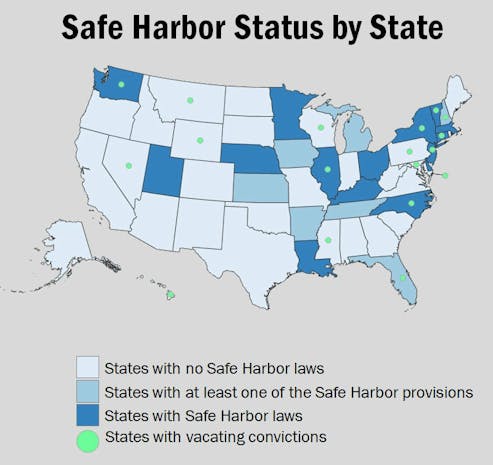

Twenty-two states have attempted to address the problem of trafficked minors by enacting safe harbor laws like the one that just passed D.C. today. Fifteen states provide full legal protections, immunity from prosecution, and rehabilitation services, while seven provide only one of these, according to Polaris, a non-profit anti-trafficking organization. In the other 28 states, minors are prosecuted for prostitution just like adults are. (Polaris awarded a "perfect score" to only three states in 2014: Delaware, New Jersey, and Washington state.)

Federal attempts to fix this patchwork of state laws have failed. The Stop Exploitation Through Trafficking Act (SETTA) of 2014 passed the House and is on the Senate's legislative calendar. If enacted, it would encourage states to enact safe harbor laws by providing Community Oriented Police Services (COPS) grants only to states that have those laws, and also calls for federal funding of a national communications system to connect victims with services.

SETTA would improve upon the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000, which establishes human trafficking and related offenses as federal crimes. Subsequent reauthorizations have strengthened the TVPA, including the creation of pilot and grant programs for sheltering minor survivors in 2005 and the inclusion in 2013 of a section that recommends states treat minors as victims and adopt laws to prevent their prosecution.

At the state level, however, the TVPA has proven largely toothless. “The federal government has limited powers over the states when it comes to child protection,” explains Samantha Vardaman, senior director of Shared Hope International. Furthermore, federal safe harbor laws, where a minor is anyone younger than 18, clash with statutory rape laws, where the age of consent or the legal age can be 16 or 17. In states like Connecticut and Michigan, which Polaris deems safe harbor–friendly states, anyone over 16 can be charged with prostitution.

The long-term effects of underage sex trafficking are disastrous. Criminal charges may remain on their records permanently, making it hard to get public benefits. While some states do allow victims to have their convictions vacated as part of their safe harbor plan, 32 still do not. Although SETTA would allow victims to qualify for Job Corps, federal law does not yet encourage states to expunge victim’s criminal records—so their childhood victimization haunts them well into adulthood, if not their entire life.

“Nobody gets out [of trafficking] at just 18,” says Frundt, who argues that adults should also have a safe harbor equivalent. She's been out of the "trafficking life" for over 15 years, she says, "and I still need counseling."

Correction: An earlier version of this story contained a footnote that stated that human trafficking "involves the illegal transport of people for exploitation." That is not always the case.