At the risk of reading too much into a single tweet, this one seems to speak to the Democrats’ post-election disarray more than any other.

I saw first-hand how a strategy of obstruction was debilitating to our system, and I have no desire to engage in that manner.

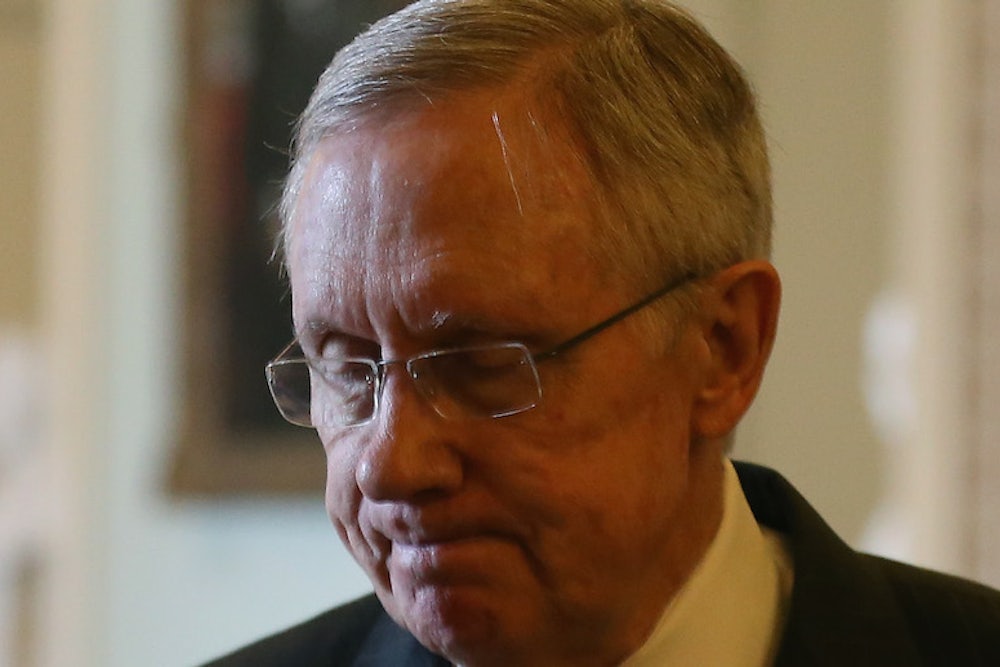

— Senator Harry Reid (@SenatorReid) November 12, 2014With respect to a handful of issues, a Democratic strategy of non-obstruction can amount to cunning, rather than surrender. Republicans are poised to pass a lot of focus-grouped, business-friendly legislation that will likely fracture Democrats. That's mostly what you hear about these days. But to assuage the right, Republicans will also probably be forced to vote on a variety of more contentious issues. And in those cases, there’s a deep strategic logic to eschewing the filibuster.

If conservatives force Republicans to hold votes on unpopular measures—pure conjecture, but abolishing the EPA, say—a filibuster by the Democratic minority would allow Republicans to disguise divisions within their ranks. If a filibuster’s insurmountable, then reluctant Republicans can vote yes, secure in the knowledge that the bill’s not going anywhere, anyhow. Remove the filibuster and suddenly future Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has to get his vulnerable members and his hardliners on the same page, or the bill fails on account of Republicans.

But I don’t think that’s what future Minority Leader Harry Reid’s talking about here. His message is a tacit acknowledgement of structural difficulties that make it harder for Democrats than Republicans to be a united, rejectionist opposition party. Their coalition includes many moderates; isn’t overwhelmed by ideological liberals; is in hock to big business; and, unlike Republicans, is invested in the idea that government should function well.

That the Democratic Party’s favorables have just fallen below the Republican Party’s favorables for the first time since the last Republican midterm blowout (and really for the first time in about a decade) compounds the problem—Democrats don't want to become even more unfavorable, and they saw what obstruction did to the House GOP's approval numbers.

The pending vote on approving the Keystone XL pipeline illustrates how these phenomena combine. Keystone probably had the votes to overcome a filibuster all along, and will definitely have the votes to overcome a filibuster in January. It might even pass by a veto-proof margin then, which moots the White House’s opposition. If voting next week instead of January gives Louisiana Senator Mary Landrieu even a small nudge in her runoff election (and I’m skeptical that it will) then Dems might as well bite the bullet now, rather than later.

But this only shows that when Democratic rank and file don’t benefit from Reid controlling the legislative agenda, they scurry for cover, lest they get caught opposing bad-but-popular ideas.

Republicans don’t face the same array of pressures, which made single-minded obstruction easy. As game theory, turning Mitch McConnell’s playbook back on the GOP is probably the right move. But if Harry Reid were to try, he’d run into people like Joe Manchin who are happy to say they won’t put up with his “bullshit.”

This article has been updated.