Election Day is less than 24 hours away and the probability of Republicans gaining control of the U.S. Senate is high. FiveThirtyEight, the Upshot, HuffPost Pollster, the Princeton Election Consortium—all of them say the chances of a Republican takeover are somewhere between 65 and 75 percent. That’s a strong consensus.

What would this mean for the next two years? Republicans say that, without Harry Reid and Senate Democrats controlling the agenda, they will be able to work with their House counterparts to pass legislation. President Obama is likely to veto most of it, they acknowledge, but that will merely play into the GOP’s hands—allowing them to set up the 2016 elections as a clear choice between a party that gets things done and a party that does not. “No question about that, he'll veto some [bills],” Mitt Romney, the former GOP presidential nominee, said on Fox News Sunday, “but I think at that point, we'll find out who really is the party of no.”

It’s true that a Congress with Republicans in charge of both chambers is likely to pass more bills than a Congress with divided control would. But would Republicans actually benefit politically? That’s not clear at all.

For one thing, the laws they want to pass might not be that popular—or at least electorally helpful. During that Fox News interview, Romney mentioned two pieces of legislation he thought a GOP Senate would pass: immigration reform and a bill to modify Obamacare’s requirement that employers provide health insurance to full-time employees. But the politics of immigration reform are tricky for both sides: An immigration bill sufficiently tough to get past the Tea Party in the House (and maybe the Senate too) is likely to alienate Latinos, at a time when Republicans desperately need to start appealing to them. As for Obamacare, the kinds of changes to the employer mandate that Republicans are contemplating could have some signficant (and negative) effects on the labor market. Obama would not have a hard time defending a veto.

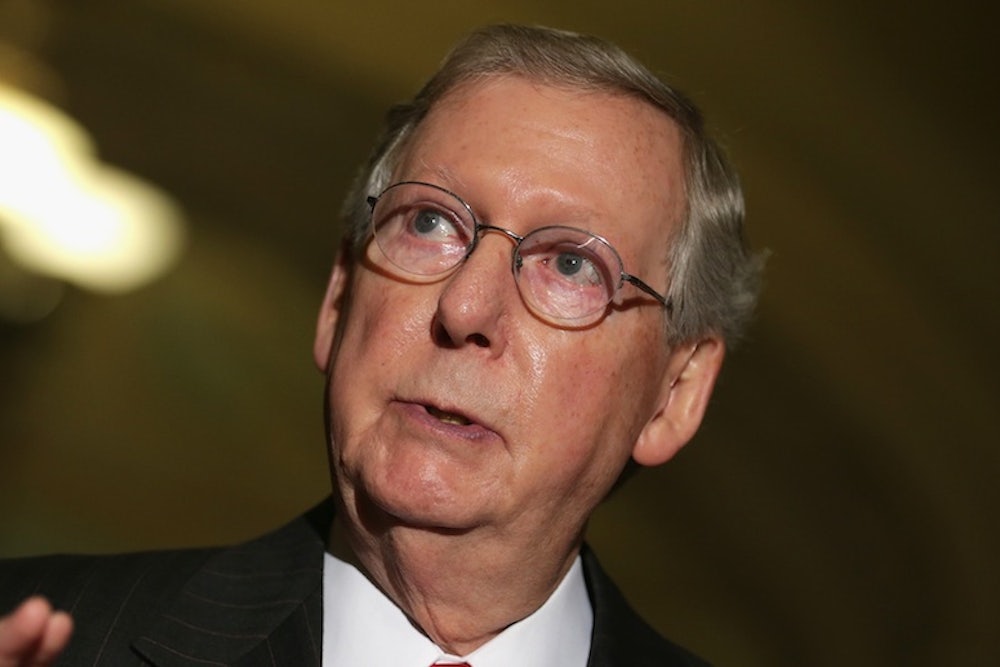

Of course, the point of passing legislation isn’t simply to change policy. It’s also to change the GOP’s image, from a party that is standing in the way of progress to a party that is trying to produce it. But that’s going to be difficult as long as the GOP keeps trying to block Obama appointments for the executive branch and judiciary. This has been a running theme of the Obama presidency: He puts forward nominees and Republicans use what leverage they have to stop those nominees from taking office. Obama has mostly succeeded in getting his people in place eventually, thanks in no small part to Reid. But things are going to change if Republicans are in change and Mitch McConnell is the majority leader. As TPM’s Sahil Kapur reported recently, conservative activists and strategists are counting on McConnell and Charles Grassley, who would be chairman of the judiciary committee, to block a wide array of Obama nominations simply by refusing to bring them to a vote.

The biggest reason passing legislation isn’t likely to make much dent in public perceptions of the GOP may be that, not long after the election, relations between Capitol Hill and the White House will start getting less attention. The argument about priorities and ideas will move out of Washington and onto the campaign trail, to be carried on by the politicians running for president. Obama will be on the ballot, but less so for his final two years and much more for what he accomplished (for better or worse, depending on your perspective) over the course of his eight-year term.

Republicans could prevail in that fight, obviously. A lot can happen between now and 2016. But passing more legislation isn’t likely to make a huge difference.

—Jonathan Cohn

News from the weekend

THE AGENDA: The president spent the weekend campaigning, but his aides are preparing for the possibility of a Republican Senate by preparing an agenda that includes trade, taxes, and infrastructure. (Peter Baker and Michael Shear, New York Times)

HOW WE DIE: Brittany Maynard, the 29-year-old with terminal brain cancer who moved to Oregon, used the state’s “Death with Dignity” law and reportedly took her own life on Saturday—just as she said she’d wanted to do. (Sarah Kliff, Vox)

EBOLA: Nurse Kaci Hickox, who fought against being quarantined after returning from treating Ebola in Africa, prevailed in court Friday. The federal judge ruled Maine Governor LePage’s attempts to keep her inside her home were unconstitutional. (Alex Page, Mother Jones)

WORK AND FAMILY: A new, narrowly focused study suggests that some women with children may actually be more productive at work. It all depends upon the timing and circumstances. (Ylan Q. Mui, Wonkblog)

GUN VIOLENCE: Eleven days after a deadly school shooting, Washington state residents will vote on a pair of competing measures on guns—one that would strengthen background checks and one that would weaken them. (Kate Pickert, Time)

Articles worth reading

2014 isn’t as good as it seems for the GOP: Nate Cohn says that this year ought to be a nearly perfect storm for Republicans, given unhappiness with Obama and the conservative Senate seats up for grabs. The GOP is likely to end up with a narrow Senate majority, but they should have done better. (The Upshot)

Saving Hillary from Wall Street: Harold Meyerson says that Clinton should pledge to follow FDR's example, and refuse to appoint big bankers to the top posts at Treasury. (Washington Post)

Passing notes: Candidates and PACs aren’t allowed to communicate explicitly, but that doesn’t stop them from swapping notes—thinly veiled as public announcements and engagements. (Alex Roarty and Shane Goldmacher, National Journal)

Under the knife, over spiders: Surgery to treat a man for a seizure disorder had an unexpected side-effect: It cured his arachnophobia. (Rachel Feltman, Washington Post)

At QED

Rebecca Leber explains why TransCanada’s newest pipeline proposal, Energy East, is the new Keystone XL. Danny Vinik says the governor’s race in Colorado could come down to feelings about the death penalty. Also at the New Republic: Noam Scheiber wonders whether he was too harsh when he declared, in his book, that Obama “fumbled the recovery.” And John Judis breaks down the social science of panic that explains public anxiety about ISIS and Ebola.

Clips compiled by Claire Groden and Naomi Shavin