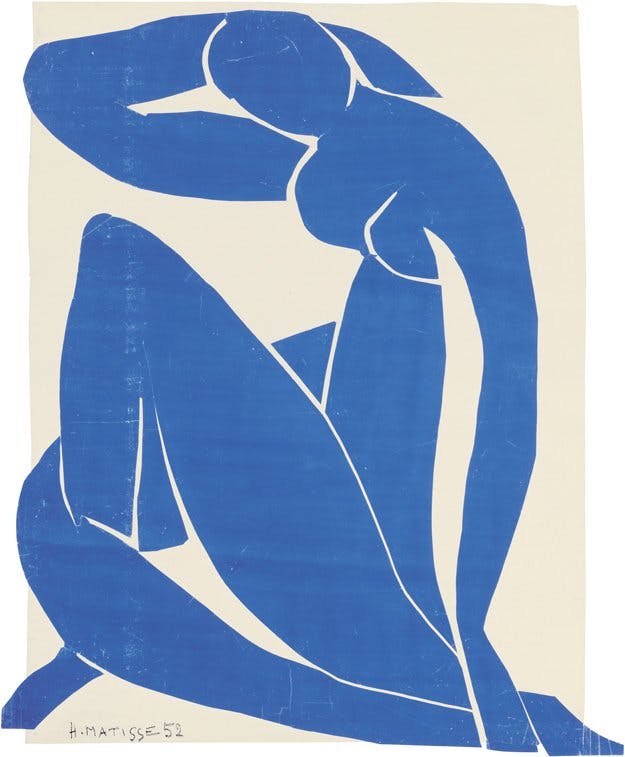

“Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” at the Museum of Modern Art, is the strangest youthquake the world has ever seen—a youthquake dreamed up by an artist in his seventies and sustained straight through to his death in 1954 at the age of eighty-four. Working with little more than an ordinary pair of scissors, Matisse was cutting into sheets of paper painted in radiant intensities of red, yellow, blue, purple, orange, and green, shaping an exotic alphabet of leaves, flowers, faces, and figures, which he then pinned and pasted together into hallucinatory crystalline visions. At the Museum of Modern Art we are plunged into Matisse’s Eden, a gathering of cut paper vignettes and panoramas so rich and varied as to suggest not a world but something even larger—a worldview or a philosophy of life. Surrounded by jungles, goddesses, oceans, and the heavens, we follow a trail of ravishing signs and symbols, drawn deeper and deeper into Matisse’s luminosity.

There was something Balzacian about Matisse’s manic energy in the last years of his life. Like Frenhofer, the aged hero of Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece, the greatest of all tales of artistic obsession, Matisse was determined to define once and for all the relationship between color and line in Western art; but instead of Frenhofer’s self-immolating doubt, Matisse offered a modernist’s triumphantly confident bolt from the blue. French poets and painters had been fascinated by the symbolic power of gem-like, hedonistic color since at least the middle of the nineteenth century. Gauguin—a painter whose achievement was part of what pushed Matisse to visit Tahiti in 1930—had given one of his finest dreamlike symbolist compositions the ringing title Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? With his cut paper compositions, in which the natural wonders are interlaced as they are in Gauguin’s work with icons and idols (a parakeet, an acrobat, a dancer, a mermaid), Matisse was asking the same sort of big, old-fashioned questions. Are the acrobats who bend over backwards representatives of the divine? And why must Icarus fall from the sky? And who are these women who appear as if by magic from sheets of ultramarine paper? Like Gauguin, Matisse took an interest in traditional iconography, both Christian and pagan, while simultaneously cultivating his own homegrown iconography. The difference between Matisse on the one hand and Gauguin and Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece on the other is that Matisse had reimagined the old romantic obsessions, with their storms and martyrdoms and immolations, as a twentieth-century champagne high.

Surely “Matisse: The Cut-Outs” is the must-see museum show in New York this fall, with Leonard Lauder’s extraordinary collection of Cubist paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art running a close second for anybody who cares about the classics of twentieth-century art. Practically since the founding of the Museum of Modern Art in 1929, there has been a special synergetic relationship between MoMA and Matisse and New York. Alfred H. Barr Jr., the museum’s founding director, devoted much of his scholarly energy to the artist, producing in 1951 a seminal monograph called Matisse: His Art and His Public. Over the years, MoMA has devoted at least half a dozen major shows to Matisse. And several Matisses in the permanent collection—especially Dance I and The Red Studio—have become emblems not only of the museum but somehow of New York itself, their bold, elegant, hell-bent, let-it-rip spirit mirroring the city at its swaggering best. With “Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” MoMA is doing something it from time to time does very well indeed—building on its own history, reaffirming the old modern religion with all the clout of the twenty-first century’s most powerful modern museum. At Tate Modern in London, where the Matisse show was on view over the summer, the galleries felt dingy and claustrophobic, and a show that should make you feel like you are floating was a bit of a slog. In New York—with a somewhat cleaner and clearer selection of works and the addition of the room-sized Swimming Pool, a MoMA treasure in storage for the past twenty years—“Matisse: The Cut-Outs” becomes the high noon in paradise the artist always meant these works to be.

Of course it remains something of a mystery what precisely Matisse had in mind as he turned more and more in the 1940s from paint on canvas to compositions of cut colored paper, some of them ten or twenty or more feet wide. There are practical matters to be considered: in the wake of life-threatening abdominal surgery in 1941, Matisse was bedridden much of the time and found painting a physical challenge. It is also important to remember that the mystery of how Matisse’s mind worked had kept intellectuals working overtime practically since he first emerged as the leader of the Fauves in 1905. His late work, for all the blithe pleasures of sensuously shaped and colored forms arrayed in fantastical heraldic arabesques, was, like so much he had done before, tailor-made to resist easy explication. Matisse was always, simultaneously, a hard-nosed problem-solver and a feverish dreamer. If he has struck many as the quintessential modern artist, it is probably because of the intensity with which he pursued in his art a pitched, ceaseless, almost textbook Freudian battle between the ego and the id. Matisse was the scientific student of his own avidities, casting a cold eye on red-hot apprehensions and emotions. Having pursued a fiery eroticism in much of the work of his middle years, who can be surprised that in the end he dreamed up the greatest impressions of an ecstatic old age the world has ever known?

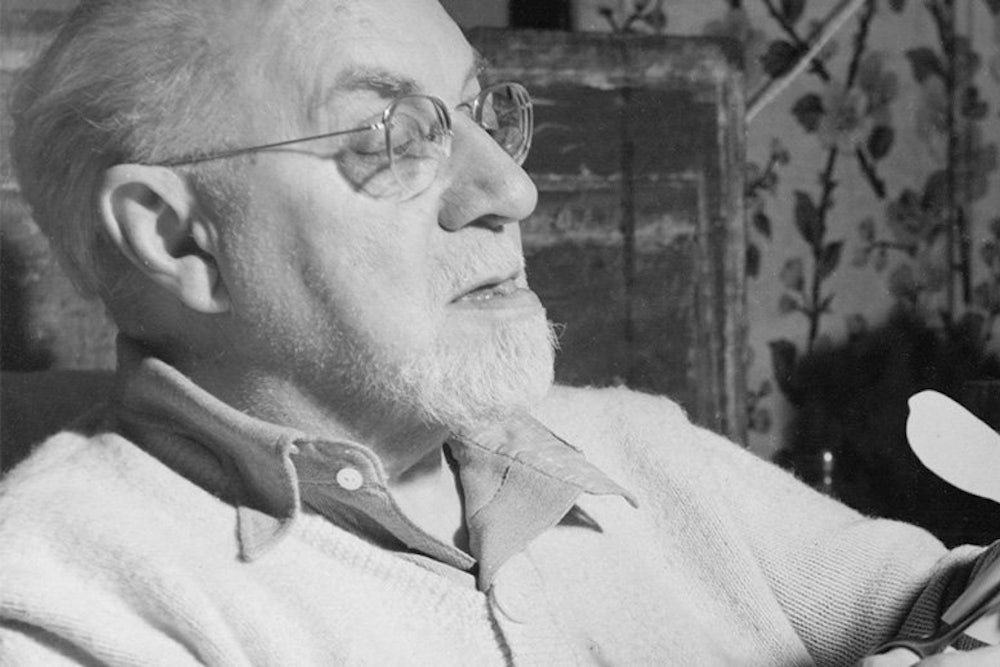

In their effort to figure out where Matisse was headed in the work of his last years, the organizers of “Matisse: The Cut-Outs” have foregrounded the enormous number of photographs (plus some film clips) that show Matisse and the rooms in which he lived and worked in these years. Occasionally the setting is a Parisian apartment, but mostly we find Matisse in an immense apartment in the Hôtel Régina in Nice or in a modest villa in Vence, on the outskirts of Nice. Wherever he is on the Côte d’Azur, the glorious sunlight is often softened by shutters and curtains to protect his increasingly sensitive eyes. You would have to be hardhearted not to be pulled in by these beguiling photographs; they are a key element in the catalogue. I remember, as an art-besotted kid in the years around 1960, being fascinated by photographs of Matisse’s studios, with the cut paper compositions covering the walls in rooms that were also filled with a sumptuous assortment of curiosities and objets d’art. We cannot help but feel that we are witnessing the daily rites of the most exotic of modern potentates when we see Matisse sitting up in the bed he had had placed on wheels so he could easily move between studios and projects, or with his massive body enthroned in a chair and a pretty young female assistant sitting (almost kneeling) at his feet. There is no question that these photographs highlight Matisse’s audaciously improvisational process, with smaller compositions in the 1940s displayed cheek-by-jowl to create mural-like effects, and larger works in the later years going through innumerable changes, the floral or figural elements moved around like pieces on a chessboard. As for what these photographic records reveal about the workings of Matisse’s mind, that is an entirely different matter.

The catalyst for “Matisse: The Cut-Outs” was the Museum of Modern Art’s restoration of The Swimming Pool, a composition of blue figures on a white ground that Matisse designed to wrap around the walls of his dining room and that had badly discolored over the years, in part because of the acidity of the burlap on which it was mounted. Karl Buchberg, who oversaw the restoration of The Swimming Pool and is the senior conservator at MoMA, organized the show at MoMA along with Jodi Hauptman, a senior curator at the museum whose essay “Bodies and Waves” is the high point of the catalogue. No doubt in part because one of the guiding spirits behind the project is a conservator, there is a very strong emphasis in the catalogue on Matisse’s process. This is reflected in the wall labels, where visitors are told that Matisse’s “vibrantly colored shapes migrated within and between compositions and transgressed architectural boundaries.” The researchers involved have neglected nothing, studying the various brands and grades of paper on which Matisse’s assistants painted in gouache, and pointing out that although the gouache colors generally came straight from the tube, at least one assistant recalls mixing colors to Matisse’s specifications.

A great deal is said in the catalogue about how the cut-outs were put together, the shapes originally pinned and only eventually pasted and mounted on canvas supports. There is some discussion about the fluid and sculptural quality of pinned papers; their positions can be readily changed and they tend to hang loose from the support, “fostering a kinetic or sculptural sensation,” as Jodi Hauptman explains in the catalogue. There may be a feeling that, when pasted down, the paper shapes become more pictorial, less sculptural, a process to be regretted—and perhaps even regretted by Matisse. I have to say I find the discussion about the pinning of the paper shapes somewhat strained. Even if much of the information about Matisse’s process has a considerable interest—certainly for those of us who can never get enough of Matisse—I am left worrying that process is being overemphasized, even dangerously so. Surely the work of many modern path-finders—who often found themselves using old techniques in new and risky ways—raises challenges for conservation and exhibition. Given that Matisse’s cut-outs, especially the largest compositions, were never designed to withstand the long-term effects of strong ambient light, one would like to know everything one can about his intentions and how the work might best be preserved. But doesn’t there come a time when questions of conservation are best left to conversations between curators and conservators? Does the public really need to know?

The problem with the repeated recourse to photographic evidence in the catalogue and the catalogue essays is that it risks turning Matisse into a more process-oriented or even performance-oriented artist than he was. Henry James, a creative spirit who was also a superb analyst of the creative process, remarked in an essay about George Sand that “a picture is never the stream of the artist’s inspiration; it is the deposit of the stream.” That’s a piece of advice I wish the curators of this exhibition had taken more to heart. At MoMA there is so much emphasis on how Matisse pushed around pieces of cut paper that the ultimate arrangements can get lost in the shuffle. Look at enough photographs of Matisse cutting out his curvaceous figures and signs, and you may begin to imagine that the act rather than the resulting work is the main event. In the catalogue, the organizers of the show suggest that Matisse’s cut-outs, as they appear in his studio, “may be seen as proto-installation or proto-environment.” They suggest, albeit gently, an association with artists who “make the activities of the studio their subject,” such as Bruce Nauman and William Kentridge. Whatever the fascinations of the journey, in art it is ultimately the arrival that matters. I realize there are many who would nowadays dispute that proposition, but I do not believe Matisse would be among them.

The Museum of Modern Art has been making the case for Matisse’s art as an instrument of radical change for so long that the curators run the risk of losing track of his deep, almost fanatical fascination with traditional pictorial genres, modes, and manners. However beguiling it may be to imagine Matisse’s studio as a sublime playroom where colors and shapes were arranged with no clear idea of where it all would lead, the truth is that more often than not Matisse had a rather precise mode or model of pictorial expression in mind. Some of the greatest among the late mural-scale works—including Large Decoration with Masks and The Sheaf—were studies for a ceramic tile wall commissioned by Los Angeles collectors. We may prefer the cut paper versions to what was ultimately produced based on Matisse’s specifications. There is some evidence that Matisse himself was not always satisfied with the way his works translated into another medium, even when that had been his intention. But Matisse’s highly disciplined procedures can sit uneasily with the contemporary museum curator’s tendency to view the artist as a situationist, focused less on art as art than on what Robert Rauschenberg (in a statement prepared for a 1959 show at MoMA) referred to as the “gap between” art and life.

When Matisse turned from the centralized compositions characteristic of European easel painting to the theme-and-variations rhythmic arabesques that we know from the great decorative arts traditions of the Middle East, he was not rejecting the challenges of a fixed set of conventions so much as he was turning from one set of conventions to another. There was about Matisse, who was nothing if not an obsessive experimentalist, an interest in pursuing a certain set of problems only so long as he believed his researches could produce fresh results. After which he would turn to an entirely different set of problems. In the 1940s, although he did several groups of extraordinary paintings, Matisse sometimes suggested that he had no more to say as an easel painter, announcing in the text that he wrote for Jazz, the album of prints based on an early series of cut-outs, that an artist “must never be a prisoner of himself, prisoner of a style.” With the cut-outs he circled back to a concern with decorative rhythm and repetition that had drawn him to the great exhibition of Islamic art in Munich in 1910. The cycle of illustrations for Jazz, as well as some of the smaller cut-outs from the late 1940s, may point to an interest in manuscript painting, not only in the Islamic tradition but also as practiced in the Early Christian and medieval worlds. Book illustration, generally speaking, fascinated Matisse, and if his illustrations of the 1940s (for volumes of Mallarmé, Baudelaire, Montherlant, and Mariana Alcoforado’s Les Lettres portugaises) reflect a reconsideration of European illustration from Renaissance Venice to eighteenth-century Paris, couldn’t it be that some of the packed images of bursting amoebas and encrusted crosses reflect an interest in Irish and Spanish illuminations done between the seventh and twelfth centuries?

Matisse brought an audacious, breakaway intelligence to traditional artistic conceptions and modes of expression. In his final decade he embarked on a mind-bending reconsideration of what may be the primal argument in European art, between the claims of line and the claims of color, which Renaissance artists and theorists had framed as a contest between the Florentine faith in disegno and the Venetian faith in colore. Matisse appreciated both the way that Michelangelo, the great exponent of disegno, insisted on the rigorously structured path of a line, and the way that Titian, the great exponent of colore, insisted on the expressive power of oil paint. Even as Matisse was producing his brilliantly colored cut-outs, he was also creating some of the most streamlined and succinct black-and-white drawings of his entire career. Summoning up faces, figures, foliage, and interiors with strokes of black ink, Matisse achieved effects that are not so much volumetric as ideographic, calligraphic. A few of these black-and-white works have been included in the MoMA installation, and they provide a much needed counterpoint to the cut-outs. The lines in the late drawings are far too independent to be tethered to color. As for the cut-outs, which Matisse said were produced by drawing with scissors, their coloristic explosions could never be contained by the rationality of a line. Matisse’s endgame had everything to do with sundering color and line from one another—and, perhaps, with seeing if color could do the structural work of line and line could achieve an empathetic power more usually associated with color. What is certain is that Matisse set color and line on their separate—dialectically fraught, perhaps ultimately irreconcilable—paths.

With the grandest project of his later years, the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, realized in the late 1940s and consecrated in 1951, Matisse gave this confrontation between color and line an architectural frame. The project had begun when a young woman who had worked for Matisse and was taking religious vows came to show him a modest stained-glass design. In the Chapel the black-and-white tile murals devoted to the Virgin and Child, Saint Dominic, and the Stations of the Cross were set in a face-off with the dazzling glass of the windows, colored light splashing across shimmering tile. Matisse embraced this immense endeavor—with the designs for the stained glass windows as well as the chasubles to be worn by the priests first worked out in colored cut paper—as an agnostic who was simultaneously bowing to tradition and problematizing tradition. Matisse was always emboldened by the constraints of tradition, which acted as a pressure on his imagination, the lid on the pot that helped keep things boiling. Did Matisse care about the Virgin? Or Saint Dominic? Or the Stations of the Cross? The answer may be that he cared about them passionately, but after his own fashion: the drama of Christianity subsumed in a pictorial drama.

What is certain is that with color and line unhooked from one another, Matisse said farewell to the great edifice of Western painting, where disegno and colore had after all was said and done worked together to construct a solidly carpentered composition, the window onto a world much like ours that the Renaissance masters had devised. The most effective of the cut-outs—whether small works with only a few elements or huge ones with dozens of elements—were built through an additive, part-to-part mode of composition, recapitulating the conventions of Middle Eastern wall tiles and carpets. Although Matisse gave most of these compositions a clear beginning and end, they also suggest infinite expansion, the multiplication of parts, with each part having its unique weight or value. The Swimming Pool may well be the closest to a storytelling composition that simultaneously fulfills all its decorative promise, the watery drama unfurling around the walls and achieving a theme-and-variations power. The paper cut-outs that sustain a naturalistic or narrative impulse—the nude set in an interior in Zulma; the biblical drama of The Sorrows of the King (which is not among the works at MoMA)—strike me as less effective, with Matisse insisting on a set of conventions that his increasingly decorative rhythms cannot support. As for Memory of Oceania and The Snail, I do not see them as the essential achievements they are often said to be. In these large compositions Matisse is caught halfway between the inward-turning volumetric logic of a painting and the outward-flowing rhythmic logic of a decoration. Memory of Oceania and The Snail are overly dependent on the good manners of old-fashioned composition, overly restricted by the pressure of the four edges of the framing rectangle.

The greatest cut-outs suggest a democracy of form, a compositional pluralism, with each shape standing its own ground, a particularity never to be trumped by the particulars that surround it. The curved, curled, many-fingered abstract protagonist of the small-sized but massively scaled Negro Boxer is solitary, complete, a freestanding avowal. The old Renaissance tension between center and edge, which gives painting its hierarchical authority, is replaced by a revolutionary belief that the center not only does not hold, but indeed must not hold. The result is something new in art: a democratic imperium.

Matisse’s invalid state in the last fifteen or so years of his life has led some to see in the cut-outs a turning away from the world. Certainly they are utopian. But their utopianism was a principled response to the actualities of Matisse’s life in those years. Anybody who reads the final chapters of Hilary Spurling’s altogether admirable biography of Matisse can see what a harrowing time he had. In the wake of his abdominal surgery in 1941, he was rarely free from pain. He knew in the early 1940s that the cosmopolitan society he had embraced was most likely headed for extinction, and he had no illusions about the world the fascists were making. If it was not hard enough to be a sick old man whose wealth at times barely protected him from the lack of basics, such as food and firewood, there was also the terror of knowing (at least to some degree) his daughter and one of his sons were involved in the Resistance—and, near the end of the war, the terror of knowing his daughter had been imprisoned by the Nazis and might well be dead. Marguerite, though tortured, survived. When in January 1945, after a three-month recuperation, she visited her father in Nice, they spent two weeks talking together every afternoon. “I was aware several times in her presence,” Matisse said, “of taking part in the greatest of all human dramas.” Who can doubt that Matisse’s final work was at least in part a cry of relief, the joyous shout of a man who had seen the ones he loved—and the world he loved—snatched from the brink of extinction?

While the late work of the great masters is always a race against extinction, Matisse responded to the challenges and depredations of age with none of the dark-toned hermeticism we know from Titian’s Pietà, Rembrandt’s self-portraits, or Picasso’s Suite 347, in all of which technique becomes outrageously idiosyncratic, a wild scrambling together of the brash and the intricate, the brazen and the inscrutable. Matisse’s late style moves ineluctably toward broad, clear, immediately evident effects. Although his cut-outs took longer to find their audience than we sometimes now imagine, and he certainly believed that at the end of an artist’s life his prime duty is to satisfy himself, there is nonetheless about the cut-outs something of the quality of a public avowal—a desire to speak frankly and openly, to present even the most enigmatic images so that a child could respond. In the very last days of his life, Matisse was working on a rose window that the Rockefeller family had commissioned in memory of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, a founder of the Museum of Modern Art. It is a cut-out design that some commentators, including Pierre Schneider in his great book about Matisse, regard as a little tame—a weakening of the artist’s powers. I find something immensely moving in the modesty of this final avowal, with Matisse submitting his own still robust form sense to the imperatives of a relatively fixed structure: the bursting rhythmic power of the rose window, which had remained pretty much unchanged since the Middle Ages.

It is the later work of Michelangelo and Bernini that comes most readily to mind when I think about late Matisse. Like Matisse, both Michelangelo and Bernini had devoted much of their lives to the representation of the human figure in all its magnificent particularity. But in their later years, they found themselves increasingly concentrating on the power of nonfigurative form as embodied in architectural form. With Michelangelo’s designs for Saint Peter’s and Bernini’s for Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, these great interpreters of all the lusts and allures of the human figure were embracing a realm of pure form, the spirit no longer enclosed in the flesh. Something similar happens in the greatest of Matisse’s late cut-outs—The Parakeet and the Mermaid, Large Decoration with Masks. We know that the impact of these works depends on Matisse’s impeccable control of each and every shape, of every last interval. But there is also a sense in which Matisse becomes, like Michelangelo and Bernini before him, a master of the bold stroke, a genius of divine generalization. In the wake of a war that came close to annihilating everybody and everything he held dear, Matisse was determined to rebuild the world he had known, where art reigned supreme. In the end he was the architect of his own Eden.