This piece originally appeared at The New Republic on July 10, 1915.

When Dostoevsky wrote that for man to be saved it was necessary that he should believe in the Russian God, he was speaking not more vaguely than most other professed researchers into salvation who work within a church. It is necessary that we should walk in the Spirit, said St. Paul. It is necessary, stammered St. Theresa in answer to an age when the awakened mind of the world was beginning to ask for clearer formulations, that grace should descend upon the essential of the soul. And past that vague passion of the seraphic doctor, theology has today advanced hardly a step towards finding out on what intellectual bases a man ought to rebuild his life if he wants to be saved from the peril of wasteful drinking or thinking, and become unalterably a part of the glory of the universe, the apprehension of which is religion. The task has been so completely abandoned by the churches that one could write a history of the moral aspirations of England since the death of Wesley without once mentioning the name of any man who was not a layman. Roman Catholicism has become more and more a social organization to control the ignorant, and a refuge for those among the educated who desire not so much salvation as an escape from democracy and the teasing discussions of life which are promoted by democracy. Protestantism has partly retroceded into an Anglicanism which is identical with Roman Catholicism in that it exists chiefly to maintain the present social system by inculcating obedience as the prime virtue; and its other part considers the emotions evoked by picturesque phrases about the Saviour on the Cross and the Blood of the Lamb to be magic experiences which automatically save the souls they visit and thus preclude the necessity for intellectual research into the salvation of humanity. That has become the fervent pursuit of the secular intelligence. It is the inquiry that looks over the shoulder of the man of science at every experiment; it is the preoccupation that sits like a judge in every artist’s brain. The discoveries of science and philosophy have opened such magic casements out of the world of appearances that they have attracted men of imagination, whose impulse it is to find out the beauty and significance of material, as strongly as they have repelled those who have staked their existence on the finality of the Christian revelation. And thus it is that the history of the research for redemption is written not in the liturgies but in literature.

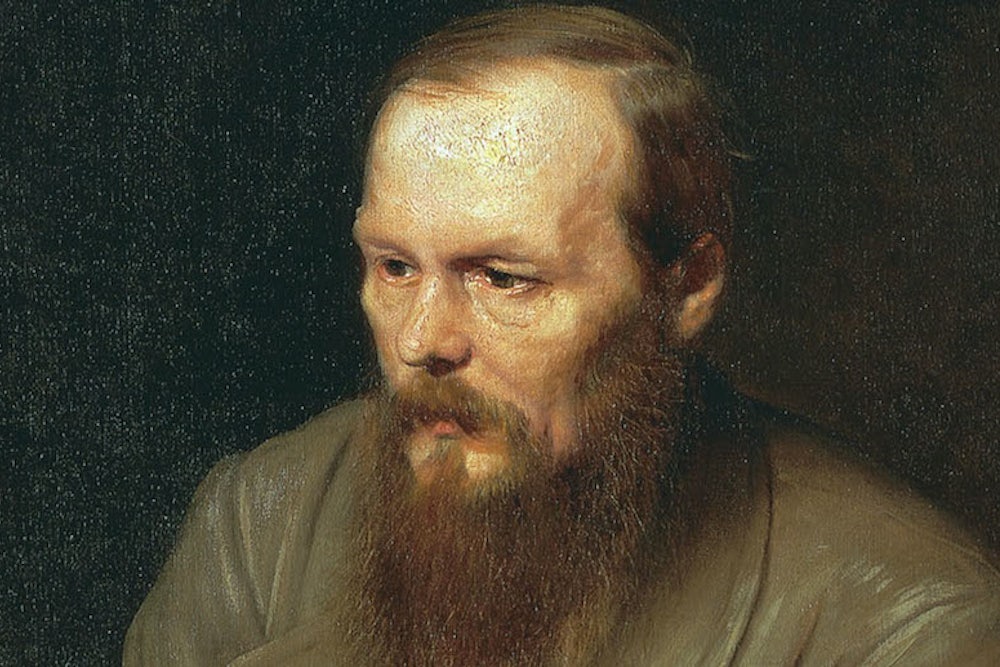

It was Dostoevsky’s misfortune that the part of this discussion which came under his notice was the pert atheism and utilitarianism which were the dregs of the draught of ideas brewed by the French Revolution, and that he lacked the education to follow thought into her hidden and wonderful ways. So, just as fervently as he took up the research—and there never was a great artist more consciously preoccupied by it—did he turn his back on the culture which had evolved its technique and vocabulary, and link himself with a church that had never heard of this mental adventure. It was his further misfortune that it should be the Greek church; for though that sect has preserved the naïve grace and kindness of the early church and practices a morning Christianity with the dew still on it, it is a savage institution, and its ritual is blood-brother to the prayers mouthed into the beard round the black rock of Mecca, or any magic words howled under the moon by naked worshippers. Yet although each one of his books proved that the church’s terminology and processes were hopelessly inadequate for the pursuit of his ideal, he clung to it with that feverish obstinacy which comes of unstable nerves. He continued to talk of ikons and venerable elders who dwelt in cells, and this peculiarly, almost comically, Russian God, who seemed to distrust the Pope as a “furriner,” until he left a confused impression that it was his puerile ambition to see the world dominated by priests with pigtails rather than by priests with tonsures. And that is the impression which will remain in the mind unless one turn to the last read and least sympathetically regarded of all his works, The Possessed, one of the most tormented books in literature.

To all of us there comes at times a mood which wakes us up at two in the morning and makes us think quickly and lucidly and despairingly, so that we lie till the dawn watching the world spin down the skies to destruction. That mood fell upon Dostoevsky at the thought of the picking, spoiling hands and minds of the Nihilists, and it stayed with him all the many days of his writing of The Possessed. “The treetops roared with a deep droning sound, and creaked on their roots; it was a melancholy morning,” he writes in his account of the duel which was one of the graceless follies of Stavrogin, the man who might have been great had he not been paralyzed by Nihilism. And he conceived the nineteenth century to be just such a melancholy morning, with Russian life creaking on its roots, and its branches roaring with the wind of doubt and hate which chased across the steppes from godless Europe. At last he becomes distraught by his own gloom, and in one of those still, interminable nights when Stavrogin wanders restlessly about the streets of the little town against whose harmonies his fellows are conspiring, he throws aside the borrowed phrases of the church and cries out his real faith in his own words. He sends out Shatov, the Christian hero, an unstable, untalented thing, redeemed only by his hunger for truth, to pluck Stavorgin by the sleeve and try to recall him to thought and action by restating the idea that had lit up their youth.

‘Science and reason have, from the beginning of time, played a secondary and subordinate part in the life of nations; so it will be till the end of time. Nations are built up and moved by another force which sways and dominates them, the origin of which is unknown and inexplicable: that force is the force of an insatiable desire to go on to the end, though at the same time it denies that end. It is the force of the persistent assertion of one’s own existence, and a denial of death. It’s the spirit of life, as the Scriptures call it, “the river of living water,” the drying up of which is threatened in the Apocalypse. It’s the aesthetic principle, as the philosophers call it, the ethical principle with which they identify it, “the seeking of God,” as I call it more simply. The object of every national movement, in every people and at every period of its existence is only the seeking for its god, who must be its own god, and the faith in Him as the only true god. God is the synthetic personality of the whole people, taken from its beginning to its end….’

‘You reduce God to a simple attribute of nationality…’

‘I reduce God to the attribute of nationality?’ cried Shatov. ‘On the contrary, I raise the people to God. And has it ever been otherwise? The people is the body of God. Every people is only a people so long as it has its own god and excludes all other gods on earth irreconcilably…. Such from the beginning of time has been the belief of all great nations, all, anyway, who have been specially remarkable, all who have been leaders of humanity…. The Jews lived only to await the coming of the true God and left the world the true God. The Greeks deified nature and bequeathed the idea of the State to the nations… If a great people does not believe that the truth is only to be found in itself alone (in itself alone and exclusively); if it does not believe that it alone is fit and destined to raise up and save all the rest by its truth, it would at once sink into being ethnographical material, and not a great people…. But there is only one truth, and therefore only a single out of the nations can have the true God, even though other nations may have great gods of their own. Only one nation is “god-bearing,” that’s the Russian people, and… and…. and can you think me such a fool, Stavrogin,’ he yelled frantically all at once, ‘that I can’t distinguish whether my words at this moment are the rotten old commonplaces that have been ground out in all the Slavophil mills in Moscow, or a perfectly new saying, the last word, the sole word of renewal and resurrection!’

Clearly Dostoevsky was not standing where he thought he was, beside the priest who rocks before the altar in vestments of cloth of gold and intones his ritual in a dialect spoken once in a corner of Macedonia but dead a thousand years ago; for this God he bore in his heart is not the God who lives within the glittering frames of the sacred pictures. He admits a little further on that faith is difficult, strangely difficult. “I want to ask you,” says Stavrogin coldly, “do you believe in God, yourself?” “I believe in Russia,” mutters Shatov frantically, “I believe in her orthodoxy…. I believe in the body of Christ…. I believe that the new advent will take place in Russia…. I believe…” “And in God?” pressed Stavrogin, “in God?” “I… I will believe in God….”

And yet while Dostoevsky was promising that he would reenter the little place of incense and lighted tapers and would bind up his belief till it was small enough to lay upon the altar, his spirit had been freed against its will and had joined the company of certain dauntless though disordered saints of the mind. He was celebrating the glory of the universe by reasserting, more hopefully than Schopenhauer, that there is a Will-to-Live which sustains and guides humanity with blind genius, and by extending Stirner’s and Nietzsche’s doctrines of egotism by preaching that not only men but nations might be strong and sinless like the angels. He had become involved in that eternal war between the proud and the humble, in which all earthly conflicts, from the feud between original genius and the academic art that loves tradition, to the hatred between the pacifist nation which leaves itself unorganized so that its children can adventure freely and the militarist nation organized for obedience, are but battles.

And he had, though he would have denied it, taken up arms with the proud. Pride was his test for everything. It was—as we see in that marvelous interlude in The Brothers Karamazov which tells how Christ came to Seville and was condemned to death by the Inquisition lest he should restore to mankind the dangerous gift of free-will—the root of his hatred of Roman Catholicism; a church which preached salvation by the subjection of the will to authority seemed to him rather a communion of cowards than of saints. He hated the materialism of his age, which declared, in the phrase that jangles like a cracked bell through The Possessed, that “the rattle of the carts bringing bread to humanity is more important than the Sistine Madonna,” because it understated the magnificent greeds and appetites of the human animal. He loved Christianity because of the willingness for sacrifice is brave, and in the words, “Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit,” rings such a call to adventure as no other religion has dared to take upon its lips. It behooved a man to be so proud of life that he would honor its young strength in little children; that he would welcome any deed that would make it sweeter, even if it were performed by the clumsy hands of an old man; that he would rejoice at every word that made its meaning clearer, even though it were hiccupped by a drunken convict. It behooved a man to remember that he was part of a nation crowned with the destiny of saving mankind, and to bear himself proudly and busily as one of its ambassadors. So he might be saved.

Thus he arrived at the nationalism which has been so much misunderstood, and has even led to the contamination of this proud and gentle soul by the approval of such a dark distruster of humanity as Pobiedonostsev. It bears no resemblance to the Black Hundred’s pretense of conserving their country by cutting at every fresh bud of intelligence and liberty. It has no sympathy with the nationalism of modern Germany; for a militarist state organized for aggression has plainly, in its delighted expectation of the slaughter of a great number of its children, lost the will to live in the lust for possessions. It was not in the last a declaration of arrogance in international affairs: the contempt thrown upon the gods of other nations in the passage I have quoted springs from a philosophical difficulty as to the uniqueness of truth which must have seemed insuperable before the days of pragmatism. It is nothing more than a counsel as to the environment most suited to the soul desiring perfection. Just as it was the chief suggestion of the reforming Carmelites of the sixteenth century that the nuns should spend less time gossiping with suitors in the convent parlor and more in the contemplative silence of their cells, so Dostoevsky saw that if young Russia wanted to be a splendid power it must stop foregathering in Switzerland to chatter like magpies about Fourier and Réclus, and sit down at home to think in terms of the life it understood.

There is nothing very mystical in the idea that the mind, even as the body, grows stronger in the country of its race. That has been proved again and again by such various manifestations as the characterlessness of colonial art, the literary tatting performed by the refined English spinsters who are to be found in the shadow of almost every Italian campanile, or the transformation of the Hindu into something tortuous and impotent by the English education. If one removes a man from his country, one deprives him of that heritage of tradition which Dostoevsky upholds as the enemy of science, but which is really the unwritten preface to science, and much more in its spirit than the jabber of misapprehended phrases he was denouncing. When, for instance, he distrusts Jews because it is the tradition of his country that they do not bear poverty so beautifully as Christians, he is plainly arriving at the conclusion by more scientific methods than are used by Houston Stewart Chamberlain when he produces “evidence” that Teutonic infants in arms have been known to burst into tears when approached by Jews. And the man removed from his country has torn from his shoulders the net of human relationship wherein he might have learnt love, which so greatly fortifies the will to live. Never will he be knit to many people by laughter over local jokes, never will he join with strangers in the shamelessly untuneful singing of old songs about past national glories. For never can one become completely assimilated to another nation; always an excess of passion here, a lack of interest there, will betray that one is a different kind of animal, with a different history and other ends. Only in one’s own country is the rose of life planted where one would have it, shaped as far as could be by the will of one’s own people, nourished by one’s own blood.

That was the nationalism of Dostoevsky. If he stated it angrily, with curses at things that are very fair, and in such loose terms that it has been used to support the attack of the bureaucracy upon the people’s will, it mused be remembered than an artist who conceives this hunger for salvation cannot work calmly. It is like standing in the darkness outside a lighted house to which one has no key. If Dostoevsky sometimes lost himself in rage as he beat on the doors, it was because he had in his heart such a wonderful dream of the light.