The Centers for Disease Control just announced new measures designed to stop international visitors from spreading Ebola in the U.S. Under the new system, anybody who has been recently to Guinea, Liberia, or Sierra Leone will be subject to what CDC officials call “active monitoring”—which will involve, among other things, mandatory temperature checks for 21 days after arrival in the U.S.

It’s not the travel ban that Republican politicians, some Democrats, and most of the public seem to want. But, if the experts are right, that’s a good thing: The new proposal will make the public safer, at least at the margins, without imposing restrictions that would, indirectly, make the epidemic worse.

Here’s what “active monitoring” will entail, if you enter the U.S. after a recent visit to one of the West African nations with ongoing Ebola outbreaks:

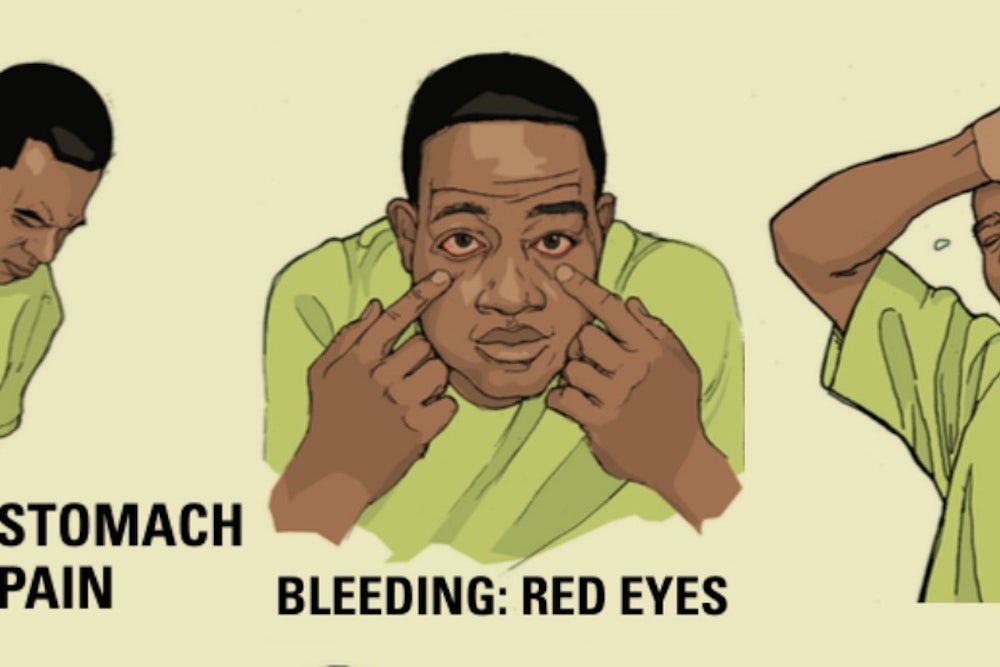

First, you’ll go through the special screening that’s been in place for weeks, getting an initial temperature check and answering questions about recent contacts. Unless officials decide to isolate you right there, because you are showing symptoms or are at extremely high risk of developing them, you’ll receive an ebola “kit” in a plain brown envelope. It will include a thermometer, as well as an illustrated guide to the disease and its symptoms, a symptom and temperature log, plus a list of important phone numbers. You’ll provide full contact information, including where you will be staying. Then you’ll be instructed to take your temperature twice a day and report in the results, to a local or state department of health, once a day.

This is what one page in the visual guide looks like:

You can see some of the other ones here.

State and local officials will have discretion over how to implement and enforce the new procedures. They can choose to arrange for in-person visits, once a day, or use alterantive means of communciating, such as Skype or Facetime. Using their own legal authority, these officials will be able to dispatch law enforcement representatives (or other government workers) to check on people who fail to report.

As of Monday, the system will be fully in place in the six states to which the majority of visitors from West Africa have been going: Georgia, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Other states should have their systems in place not long afterwards. Why the staggered roll out? CDC officials told me they prioritized their efforts by working first with the states likely to have the most visitors—and then coordinating with the others.

On a conference call announcing the new policy, CDC Director Thomas Frieden noted that it was very similar to the regime that Nigeria put into place after a visitor brought Ebola there and infected a number of people. Nigeria was able to stop the disease from spreading and on Monday, the World Health Organization declared Nigeria “ebola-free” because no new cases had emerged in six weeks. (The new program is also nearly identical to an idea that the New Republic sketched out last week.) One reason that this sort of scheme works is that Ebola patients don't appear to be contagious until they show symptoms, typically starting with a fever, and it takes contact with bodily fluids to transmit the disease.

The new measures may not be enough for the political leaders who want to refuse entry altogether for visitors from the affected countries. As they see it, only a total ban will keep ebola from coming to and spreading in the U.S. But public health researchers and officials have warned repeatedly that such a comprehensive ban would be unlikely to do much good and might actually cause harm, by slowing the flow of aid workers and supplies to West Africa—where, in contrast to the progress here and in countries like Nigeria, the epidemic is still raging.

Two of those experts seemed optimistic about the new measures when I contacted them on Wednesday:

"It is carefully layered, thoughtfully designed and will likely be effective," said Howard Markel, a physician and historian of epidemics at the University of Michigan. "Remember, when employing socially disruptive measure or for that matter specific therapies, you don't use a bazooka when a BB gun will do. These measures are in no way a BB gun, but they carry the advantage of not inciting restrictive travel bans against U.S. citizens or having a situation where the African nation in question won't allow American, etc., health workers let alone military advisers into their country."

"I think this really seals the leaks with regard to people entering the U.S. from those countries," said Melinda Moore, a physician and CDC veteran who's now at the Rand Corporation. "The numbers are relatively small. It will be interesting to see if this is really enforceable. It had better be."

Update: I added a little more context about how Ebola is transmitted.