Military heroes acquire cultural resonance by being larger than life. They upset empires and found republics, as did George Washington. After vanquishing their foes, they become presidents, as did Ulysses Grant and Dwight Eisenhower. They succumb to enormous character flaws, as did Douglas MacArthur, who is as famous for being fired by Harry Truman as he was for his World War II battles or for his brilliant landing at Inchon. They have personalities irresistible to Hollywood. George Patton thrived on screen, in Patton (1970), because of his unapologetic toughness, his salty speech, his contempt for following the rules. His abrasive personality is cinematic proof of his greatness on the battlefield. Only such a fierce man could have driven his tanks into the heart of Nazi Germany.

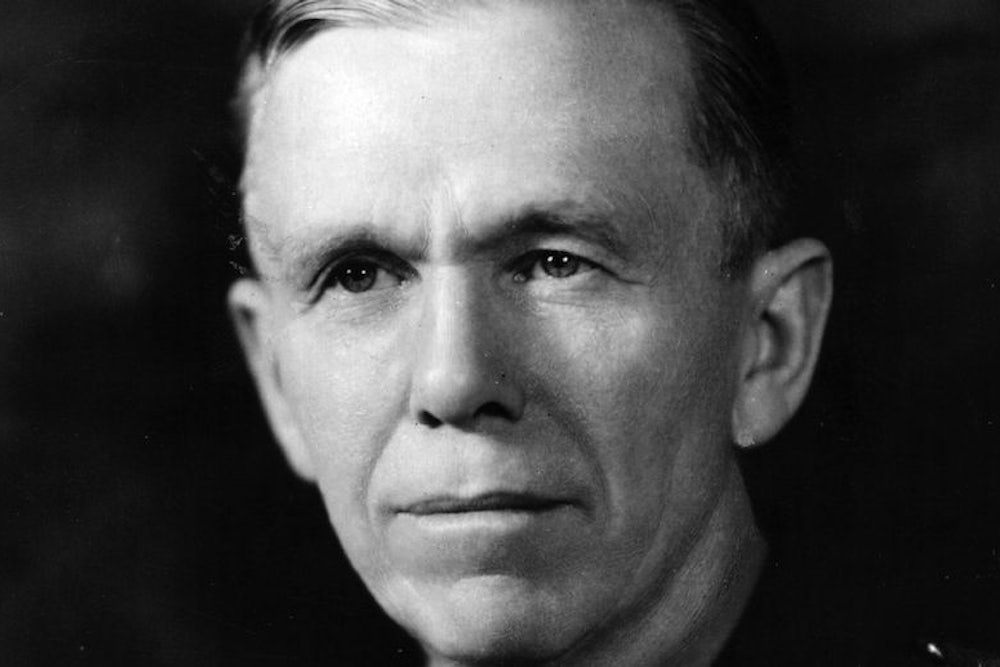

Of vastly greater stature than Patton, George Marshall has never been the subject of a Hollywood biopic. He has not quite been forgotten. His name is forever commemorated in the Marshall Plan. But neither does he have any real place in American cultural memory. He is a monument without a profile and hence a challenge to his biographers. His most recent biographers are Debi Unger, an editor at Harper Collins; Irwin Unger, an emeritus professor at New York University; and Stanley Hirshon, author of biographies of General Sherman and General Patton. A professor at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center, Hirshon died in 2003. They try to get behind the monument in George Marshall: A Biography. Still, they have a hard time interpreting this elusive man. At best they make wintry allusions to his character, to “his reticence,” “his limited social give,” “his austere ethic” and “unbending persona.” (Marshall refused to laugh at FDR’s jokes.) His personal life was entirely free from scandal. Even his heroism was somehow private.

In this biography, we see Marshall’s heroism reflected in the eyes of others. He “could mesmerize Churchill” according to Churchill’s private secretary, Jock Colville. Truman declared Marshall “the greatest military man that this country ever produced—or any other country for that matter.” A State Department employee who worked under Marshall, Charles Kindleberger, thought that Marshall “was Olympian in his moral quality.” There are so many quotes testifying to Marshall’s greatness that they cannot be dismissed as political boilerplate. Yet Hirshon and the Ungers offer little commentary on Marshall’s character, treating it as one might a personnel file, pointing out areas of strength and weakness, achievement and failure. If Marshall’s career is meticulously analyzed, his heroic presence vanishes into the wooden prose of this sober, unemotional book.

A heroic presence is far more difficult to comprehend than the discreet decisions of a statesman or a general. It is especially difficult in Marshall’s case because he did not write his memoirs or leave a trail of revealing letters and diaries. This presence, though, is the heart of his story. It consisted of his effort to look ahead and to press for military readiness in anticipation of war. It consisted of his intuitive sense that the democratic nations had to cooperate in prosecuting World War II and then in administering the peace, to do in the 1940s what they had failed to do after World War I. It consisted of his persuasiveness. Marshall was no orator, no Churchillian master of words, as he himself observed when accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953, the same year Churchill was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Marshall convinced by his calm, unglamorous presence more than by his words. Others may have thought up the Marshall Plan. It was Marshall who swayed public opinion and Congress to enact it.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1880, Marshall’s regional sympathies lay in Virginia. A descendant of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, George Marshall was “susceptible to the Virginia myth,” the authors write, and cultivated an “adopted persona as a Virginian.” After attending the Virginia Military Institute, Marshall was posted to the Philippines. When he returned to the U.S., he worked at the Infantry and Calvary School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, a position that impressed on Marshall “America’s military unpreparedness.” America was not ready for World War I. After the U.S. entered the war, Marshall served as an aid to General John Pershing, planning battles and trying, with Pershing, to make the case for universal military training.

Marshall distinguished himself in World War I, but he did not gain combat experience. As the Ungers and Hirshon note, “he would never lead men in battle; he would remain a desk officer, and a top administrator to the end of his army career.” It was precisely his administrative talent that advanced his career, as he moved from post to post in the 1930s, a military man on the make and a manager who could successfully implement the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program. All of this brought Marshall to the attention of Franklin Roosevelt who agreed with Marshall that the secret of Munich—of appeasement—resided in military readiness: Britain and France were diplomatically weak because they were less militarily prepared than Nazi Germany. FDR named Marshall Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, a responsibility Marshall assumed on September 1, 1939, just in time for World War II.

Marshall devoted himself to organizing and training the army, which would expand from 275,000 before the war to some eight million during the war. The Ungers and Hirshon give Marshall mixed grades for his wartime record. On the one hand, Marshall clarified the Allied command structure, which was always at risk of falling into division and incoherence. On the other hand, he lost out to FDR and to the British in strategic arguments about invading North Africa, while “his role in the Pacific was often hesitant and constrained.” The army he had trained often did badly on the battlefield. If some of the generals he advanced (like Patton) took on the aura of legend, some of Marshall’s other appointments fared poorly, leading the Ungers and Hirshon to air their “reservations about Marshall’s judgment of men.” This bland criticism is undeserved by someone who promoted Eisenhower above more senior figures, in the military hierarchy, and who later encouraged the careers of George Kennan and Dean Acheson at the State Department. Marshall was never intimidated by the talent of others.

The Ungers and Hirshon strike notes of revisionist caution regarding Marshall’s tenure as Secretary of State (1947–1949). He had a “misguided opinion of Stalin’s good intentions,” a circumlocution that may have applied in 1946 but was no longer true in 1947. In China, Marshall was too optimistic about the prospect of reconciliation among the communists and the nationalists. The Marshall Plan was less Marshall’s singular achievement than the handiwork of his Undersecretary of State, Dean Acheson. Truman cleverly called it the Marshall Plan to give it the imprimatur of a World War II hero and not of a divisive president trying to get Congress to approve European aid. “Marshall was not NATO’s father,” the Ungers and Hirshon continue, even if he embodied its spirit. NATO’s father, they contend, was Britain’s Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin. Marshall opposed the creation of the state of Israel, and on this he was overridden by Truman. In sum, “the performance of George Marshall in many of his roles was less than awe-inspiring.”

In their search for a statesman’s grand gestures, the Ungers and Hirshon devalue the challenge of coordination in World War II and in the early Cold War. Moving the U.S. to a wartime footing, between 1939 and 1941, was a Herculean task. Keeping the unruly Allies—the Soviet Union, Britain, and the U.S.—behind the common cause of fighting Nazi Germany was not just a military job. It was a diplomatic job, and Marshall excelled at it. Turning back the wave of isolationism that immediately followed the defeat of Germany and Japan was political work, as was the joining of the State Department, the White House and Congress into a coalition for the Marshall Plan. In American history, only George Washington and Dwight Eisenhower can compete with Marshall in the combination of political and military skill.

For a military man, Marshall’s heroism was peculiar. It did not arise from his conduct on the battlefield. It arose from his modesty, including “a modest daily schedule that often ended at three or four o’clock in the afternoon” and his avoidance “of lucrative corporate board memberships so commonly available to retired high military officers in our more avaricious times.” Most importantly, Marshall’s modesty flowed from the constitution, preserving the military’s deference to civilian politics at a time when the U.S. military was growing exponentially in resources, power and scope. Born into a country almost indifferent to matters of national security, Marshall was named Secretary of Defense in 1950, and he retired from public service in 1951, leaving it for others to run a nuclear-armed global superpower. He was the hero who did not do too much, but his sense of proportion and his aggregate contributions to the defense of democracy are genuinely awe-inspiring.