In recent weeks, tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds fleeing the Islamic State have crossed into Turkey. Meanwhile, Turkish security forces have clashed with Turkish Kurds trying to go in the opposite direction—to join their Syrian brethren in the fight against IS on the other side of the border. This past week, Syrian Kurdish leader Salih Muslim claimed that Turkey said it would allow these Kurds to enter Syria, but no such action has been taken.

The Turkish government's vacillation underscores a major dilemma for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and modern Turkey itself: Can a policy of Islamism and multiculturalism coexist? The answer to that question is especially relevant for Turkey's Kurds, who are being forced by recent events to choose between their deeply-felt Kurdish nationalism and new vision of liberal post-nationalism.

The founder of the modern Turkish republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, established the state on the principles of secularism and nationalism. For the better part of a century, those who didn't support this vision of Turkey were marginalized. The Kemalist state repressed, often violently, any efforts to articulate explicitly Islamic or Kurdish identities.

The AKP rose to power precisely because it was willing to challenge the traditional orthodoxy of what it meant to be a Turk. Over the past decade, the party has gained both praise and scorn for its efforts to reform the doctrinaire and heavy-handed versions of state secularism and Turkishness that long defined the Republic of Turkey.

After years of being oppressed by militant secularism, Islamists embraced the AKP’s promise of a new political voice and an elevated status in Turkish society. Most recently, the AKP lived up to those promises by removing austere bans on headscarves in public spaces, thereby allowing pious women to participate in state institutions without compromising their beliefs.

On the Kurdish front, the AKP has gone further then any other party to recognize the minority’s cultural rights. Thanks to reforms implemented since 2002, use of the Kurdish language is becoming more widespread: from a state-run Kurdish television channel to Kurdish instruction in universities to political campaigning. The AKP has also pursued controversial negotiations with imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan, which could result in a peace deal and amnesty for thousands of PKK fighters.

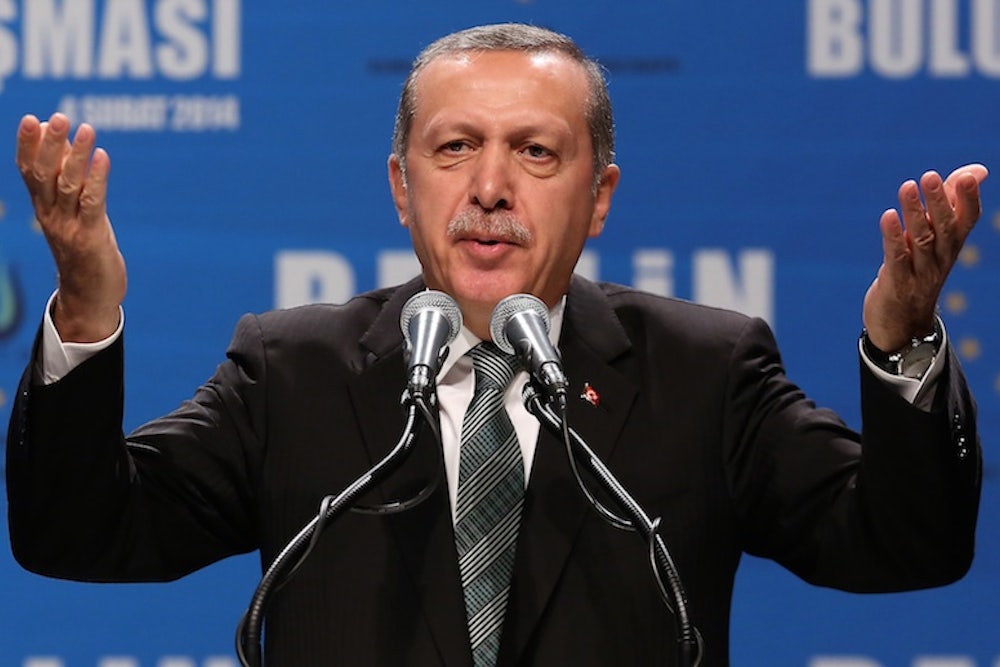

Up until now, these two policies were pursued simultaneously and were not seen to be mutually exclusive. Turkey's president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, used religious rhetoric in his outreach to Kurds—saying, for instance, that it was particularly tragic when Kurdish and Turkish mothers recited the same Muslim prayers at the funerals of their fallen sons—but also couched his challenge to state secularism in a freedom-and-rights rhetoric designed to appeal to Kurds. Thus, the AKP managed to placate both constituencies just enough that progress with one did not lead to outrage from the other.

Now, however, it seems that these two policies are coming to a standoff.

With Syrian (and foreign) Islamist opposition fighters crossing and re-crossing a porous border with Syria over the past three years to to fight, regroup, and fight some more, many in the global media have blamed the AKP for contributing to IS's growth. Some go further and claim that Turkey did not just turn a blind eye, but that the AKP's explicitly sectarian rhetoric encouraged young Turks to become jihadists. Recent critiques from Turkey’s Kurdish leaders, though, have been the most pointed of all. In explaining the Kurdish party’s opposition to a recent bill authorizing Turkish military intervention in Syria and Iraq, Kurdish Parliamentarian Ertuğrul Kürkçü stated, “You [government] were bystanders to the ISIL massacres. . . you were the ones who supported ISIL, and you are still supporting it.”

Indeed, even if Erdogan publicly announced that Turkey has joined the anti-IS coalition, the risk of upsetting the AKP’s conservative base, who perceive recent airstrikes as Western intervention against Muslims, is a real one. It may explain, at least in part, why the Turkish military has yet to take action against IS despite parliamentary authorization to do so.

Many Kurds see the AKP’s ambivalence toward IS as evidence of where its true priorities lie. "If four Kurds get together, the state will break them apart. Of course they can stop [IS] if they choose to,” said a Kurd living in an Istanbul suburb known to be a IS recruitment hotspot. Prominent journalists are even questioning whether Turkey's support to IS actually stems from a desire to crush the Kurds once and for all. PKK leader Murat Karayilan speculated recently that the Turkish government allowed IS to capture Kobane, one of three cantons administered by the PYD (PKK’s Syrian affiliate), in order to secure the release of its hostages.

But tensions have now metastasized from rhetoric to full-on violence. This week, over twenty people were killed when Kurdish protestors took to the streets to demand more assistance from the Turkish government in Kobane. These developments now risk upending the entire peace process.

The Kurds were the first group seriously fighting IS on the ground. In the face of the jihadist threat, notoriously fractious Kurdish groups from throughout the region have unified to fight together. And with the U.S. arming the Iraq's Kurdish peshmerga, the PKK (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization) is now asking for weapons from the West as well. Amid the tumult in the region, Turkey has ignored its previous red lines, like Kurdish control over Kirkuk in Iraq or potential independence of Iraqi Kurdistan. But when it comes to its own Kurds, after a 30-year war that has cost more than 40,000 lives, Turkey's giving weapons to the PKK may be a step too far.

The AKP’s willingness to deal with the PKK will not only depend on the party’s own identity crisis, but on the outcome of a crisis within the PKK itself. Journalists still regularly describe the PKK as a Kurdish independence movement—and for decades, it was. But more recently it has moderated its demands, often relying on sophisticated theoretical critiques of nationalism to do so.

Rather than seek Kurdish independence, the group, along with its Syrian affiliate the PYD, has promoted the idea of Kurdish autonomy within federated Turkish and Syrian states. Some skeptics suspect this conciliatory rhetoric is just a negotiating ploy, but Kurdish leaders insist their about-face is simply in keeping with the realities of history as proven by recent scholarship. Indeed, some statements from Abdullah Ocalan sound more like the pronouncements of an eager graduate student than a terrorist leader:

In isolation I grasped the alternative modernity concept, that national structures can have many different models, that generally social structures are fictional ones created by human hands, and that nature is malleable. In particular, overcoming the model of the nation-state was very important for me. For a long time this concept was a Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist principle for me. It essentially had the quality of an unchanging dogma... When you said nation there absolutely had to be a state! If Kurds were a nation they certainly needed a state! However as social conditions intensified, as I understood that nations themselves were the most meaningless reality, shaped under the influence of capitalism, and as I understood that the nation-state model was an iron cage for societies, I realized that freedom and community were more important concepts. Realizing that to fight for nation states was to fight for capitalism, a big transformation in my political philosophy took place. I realized I had been a victim of capitalist modernity.

In this light, when Ocalan declares through his intermediaries that more Kurds should learn Turkish, he is merely reflecting a reality obvious to many observers. Anyone who has ever watched PKK propaganda videos has seen militants joking with each other in fluent Turkish, while Kurdish nationalists in Diyarbakir complain that popular Turkish soap-operas have done more to teach the younger generation Turkish than state oppression ever could. Moreover, with Turkey’s economy booming, many Kurds have found work in the Western Turkish cities of Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir. They and their relatives still in the region they call Kurdistan realize that independence would just mean a new set of borders dividing families.

The real opportunity for the Kurds today is not, as many pundits excitedly predict, that they finally have a shot at complete independence. Instead, they finally have the good sense and intellectual foundation to pursue much more modest but pragmatic goals. While the heroic defense of Kobani has won the PKK and PYD a new wave of Western support, Kurdish leaders would do well to remember that their evolution from Stalinism to liberalism has also been crucial to this newfound legitimacy. More importantly, the temporary consensus amongst various Kurdish factions cannot hide the long history of Kurdish infighting. This fractious past, along with the dispersion of Kurds within Turkey, mean that a loose affiliation of the semi-autonomous Kurdish parts of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey might actually be a lot closer to what Kurds really want and need than a nominally unified but unstable and isolated Kurdistan.

The real question now is whether the AKP and PKK can find common ground. Here is where the nightmare of the Islamic State is instructive. Much has been made about how the AKP wants to replace an old-fashioned version of Turkish nationalism with that of a religious community built around the Muslim idea of the Ummah. So does IS. But when you compare the vision of post-nationalism the AKP spent the last decade promoting—breaking down regional borders through free transit, low tariffs, and trade promotion—it sounds a lot more compatible with the PKK’s newly endorsed secular post-nationalism than the savagery of IS.