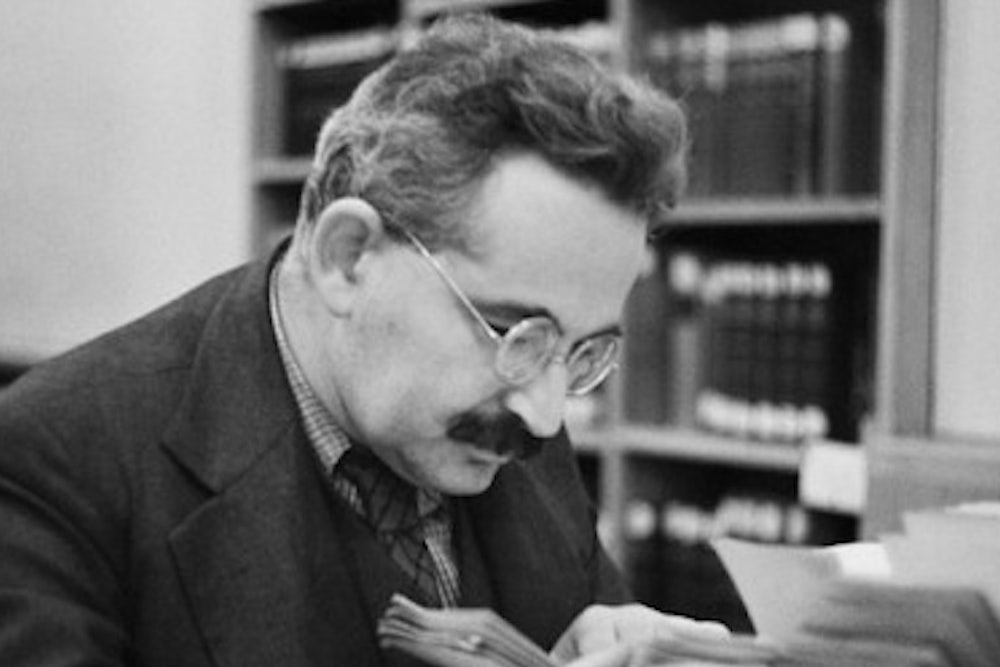

I found German writer Walter Benjamin through my middle-school history teacher. He was my first adult crush, barely 21 and a graduate student with long hair pulled back in a ponytail and wire-rim glasses. I was twelve, a sad, little misplaced girl, with a ponytail and big, unwieldy dreams. It was the Arcades Project that led me to Benjamin, his unfinished effort to catalog and critique Parisian city life through ephemera. I lived in a town just outside of Paris, and I was trying to turn my own youthful observations into writing. Back then, I still imagined the world with poles of good and bad. This provided easy, naive taxonomy for human beings, a sense of absolute justice and clarity of character.

From the Arcades Project, I found my way to Benjamin’s other essays and eventually “The Work of Art,” for which he is perhaps best known. Written in 1936, this essay introduced the idea of an ineffable essence—an aura—of a work of art and the benefits and limits of the advent of technology like photography. I came to the essay at a time when I thought I was in love with a photographer. I think I may have even sent him a link to this Benjamin essay, hoping for a discourse. In retrospect, he was much more interested in sleeping with me than literary discussion. I fell more in love with Benjamin and less in love with the photographer. Eventually, though, I let the essay go, and the photographer go, and, naturally, both came back around.

The essay came back to me when I attended a show of the work of one of my favorite artists, Cy Twombly, at the Gagosian Gallery in New York. The show featured both his large-scale neon works and, on another floor, his photography—images that were taken up until his death, just two years ago. Sometimes it takes a few good men to find your way around to what exactly you were looking for. So, in walks Benjamin just behind Twombly.

Of course, Instagram has provided ample opportunity to bring Benjamin into the modern era. And “aura” has been invoked in the context of the multiplied and proliferated media of this moment, though it may not have been described as such. It took this encounter with Twombly, however, for me to revisit Benjamin and the ambiguities of Benjamin’s argument.

As curator, artist, and author Edmund de Waal writes in the exhibition catalog, Twombly's photos have “an aura." de Waal also says of Twombly, “His work is a glorious list of transitive verbs, an iterative inhabitation of the present moment," and then references a picture of things in a yard sale, noting, "objects become as memorialized as Homer's thousand ships." Twombly was also a words man, a reader. But words and objects are not so far apart. Benjamin cites ritual as necessary for art, when this is lost in exhibition, authenticity turns to commodity. Twombly, also, saw ritual as lending meaning to objects.

I started working this over and over in my head, because it was confusing, to say the least. Benjamin’s stance was that aura did not exactly exist in reproductions, like photographs. Yet Twombly’s photos did have “it.” de Waal says so, and I felt it. The fact that Twombly’s photographs could command space and attention does not dismiss Benjamin, rather it reinforces him. Even Benjamin admitted the duality of his stance. Mechanical reproduction devalues art, as art no longer inhabits a single object, though it also enriches cultural perspective, offering new points of view.

Just look at the way Benjamin wrote about film—the ambiguities are right there. Benjamin saw film as more sophisticated than photography. It was still mechanically reproduced, but it allowed the viewer to see angles, pull back, pull in, observe objects, and work fast enough to capture a longer segment of what no longer exists. The hand and eye or shutter cannot work at this frequency. No human being can process at the frequency with which images are now proliferated. This duality—the idea that something can both have an aura and not—in Benjamin, in Twombly, reminded me, in an indirect way, of the messiness of any relationship.

We can be quick to dismiss the importance of a very basic human connection when we read, wanting to find a more complex reason to love a work, when, in fact, a work of literature simply makes us feel better about ourselves or more acutely aware of peculiar human dynamics. I’ve always been pricked into my own reality by essays: Benjamin, Joan Didion, Cynthia Ozick, and Michel de Montaigne. For a long time, I was married only to non-fiction. I could barely understand social nuances in real life, so it was even more daunting to tackle them second-hand. As I grew older, even the definitive conclusions of essays changed shape: these, too, were just one person’s astute version of make believe. Benjamin’s writings on his very particular world will continue to illuminate my own.