The enduring likelihood that Republicans will claim control of the Senate in November is catnip for bipartisan nostalgists who, motivated by longing more than anything else, believe a fully Republican Congress will be more likely to reach accord with President Obama than the current, divided Congress.

New York magazine's Jonathan Chait correctly identifies the flaws in their reasoning. But he takes things a step further and argues that a Republican House and Senate will, if anything, exhibit more partisanship and rancor than the current arrangement.

“[P]olitical scientists have found that voters hold the president solely responsible for outcomes,” he notes. “This does not give a Congress controlled by the opposing party an incentive to cooperate — it gives Congress controlled by the opposing party an incentive not to cooperate.”

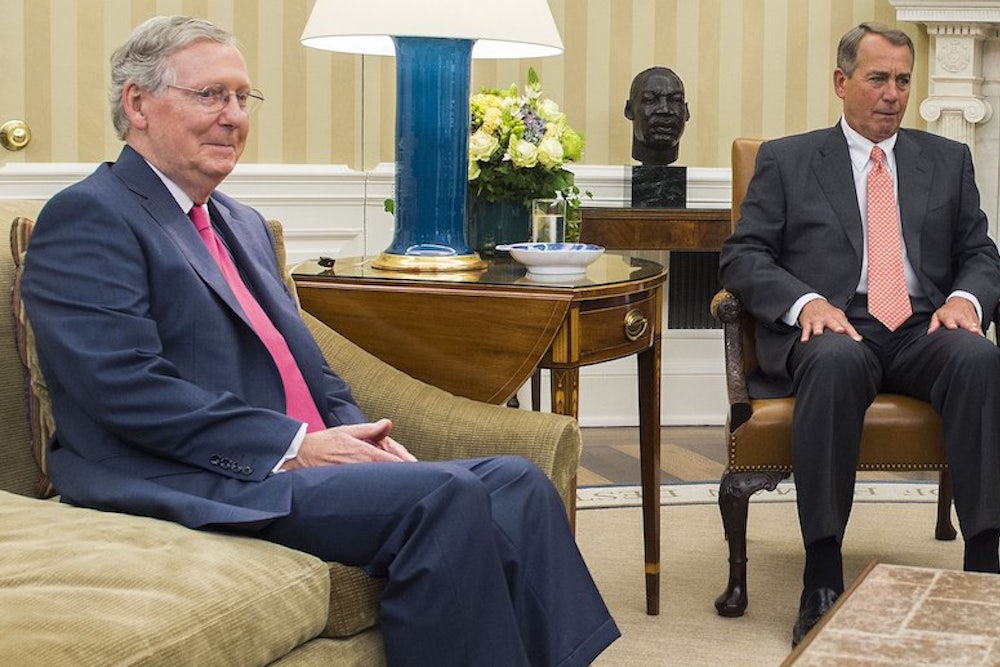

This observation is correct, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that a president whose party only controls one chamber of Congress will be able to cut as many or more deals than a president whose party controls neither. And while a House and Senate lead by John Boehner and Mitch McConnell, respectively, could plausibly devolve into unmitigated chaos, they could also manage to hold things together well enough to cut deals with a weakened Obama.

Bipartisanship nostalgists would wrongly view that outcome as a vindication of their logic, and of the merits of bipartisanship itself. But the truth would be much less interesting. The question is whether moving negotiations between Congress and the White House to the right would make agreements—bad agreements, perhaps, but agreements nonetheless—easier to reach. And there are decent reasons to think it might. Just because bipartisanship nostalgists are reaching their conclusion in error doesn’t mean the conclusion itself erroneous.

The crux of Chait’s argument is that these imagined deals would have already happened under the current arrangement. For the nostalgists to be right, “you would have to imagine that there are deals that could be struck between the Republican House and President Obama that the Democratic Senate would block but that a Republican Senate would agree to.”

As it happens, I think there probably are some. To take one prominent example, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid broke publicly with President Obama after his State of the Union address earlier this year and torpedoed legislation, backed by the GOP and Obama, to fast-track trade agreements.

But this is also a confusing way to think about the dynamic. When the White House and Congress negotiate, it isn’t generally the case that the president first comes to an understanding with the House speaker and then asks the Senate majority leader for his blessing. Instead, the three entities need to haggle and reach an agreement among themselves that's amenable to all.

A better way to think about the difference between a Democratic and GOP Senate is to look at where along the political spectrum the center of negotiations will lie. Right now, because Democrats control the Senate, it lies further to the left than it would under GOP control, which makes all tentative agreements much harder to sell to the Republican House.

Move things to the right a bit, and the question becomes whether Obama would be willing to cut more conservative deals that aren’t currently in the offing. I don’t know what the answer is, but it isn’t crazy to think a lame-duck president might sign off on legislation that would, under the current arrangement, be tantamount to surrender. And when you look at it that way, it’s reasonable to imagine that Obama-Boehner-McConnell might cut more deals than Obama-Boehner-Reid. They’d just be worse deals.

They also probably wouldn’t be the kinds of deals that’d satisfy hardline conservatives. As I’ve argued recently, a Senate majority would test the Republican Party in new and unpredictable ways. And if the disagreements simmering within the GOP end up boiling over, then a Republican Senate would actually make Congress even more dysfunctional. Obama could likewise decide the deals on offer aren’t worth cutting. Either outcome would devastate the nostalgists. But neither one is baked into the partisan arrangement.