The Nixon Defense: What He Knew and When He Knew It by John Dean (Viking)

“You know,” Richard Nixon told his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, on April 9, 1973, “with regard to recording what goes on here in the room: I feel uneasy about that ... uneasy because of the fact it’s even done.” Sitting in the Oval Office, his words captured by the very machines he was describing, Nixon began a long meditation about his secret surveillance. He had installed the taping system in mid-1971—in the Oval Office, in his Executive Office Building hideaway, and in his Camp David study—to create records of his discussions for when he wrote his memoirs. But now, realizing how much time and effort it would take to review the reels, Nixon sighed, “I’m never going to want to read all that crap. I never will.”

Minutes later, Nixon arrived at a solution. “I’d like you to stop it now,” he instructed Haldeman. “And second, I think we should destroy them, because I have so much material right now in my own files that I’ll never be able” to listen to the tapes. His choice of words was telling: destroy is strong language to use about material that’s simply superfluous or unwanted, but it is the word Nixon continued to use throughout his life when speaking or writing about the tapes, typically claiming that he wished he had “destroyed” them. The unease he felt was clearly about something other than the chore of wading through them.

This previously unpublished exchange with Haldeman is one of many signs in The Nixon Defense, the important new book by his former White House counsel John W. Dean, that Nixon recognized his own criminal culpability in Watergate and knew that the tapes bore the proof. But when Nixon proposed to destroy them Haldeman pushed back, noting that these reels contained historic material about the opening of relations with China. Haldeman and Nixon both worried that their national security adviser, Henry Kissinger—a compulsive note-taker—would, in writing his memoirs, inflate his own role in the China overture. They agreed that Nixon should merely modify his taping policy, recording only his discussions about foreign policy. He would also expunge the numerous disparaging remarks about Kissinger and Secretary of State William Rogers. And, Nixon added, “I don’t want to have in the record the discussions we’ve had in this room about Watergate.”

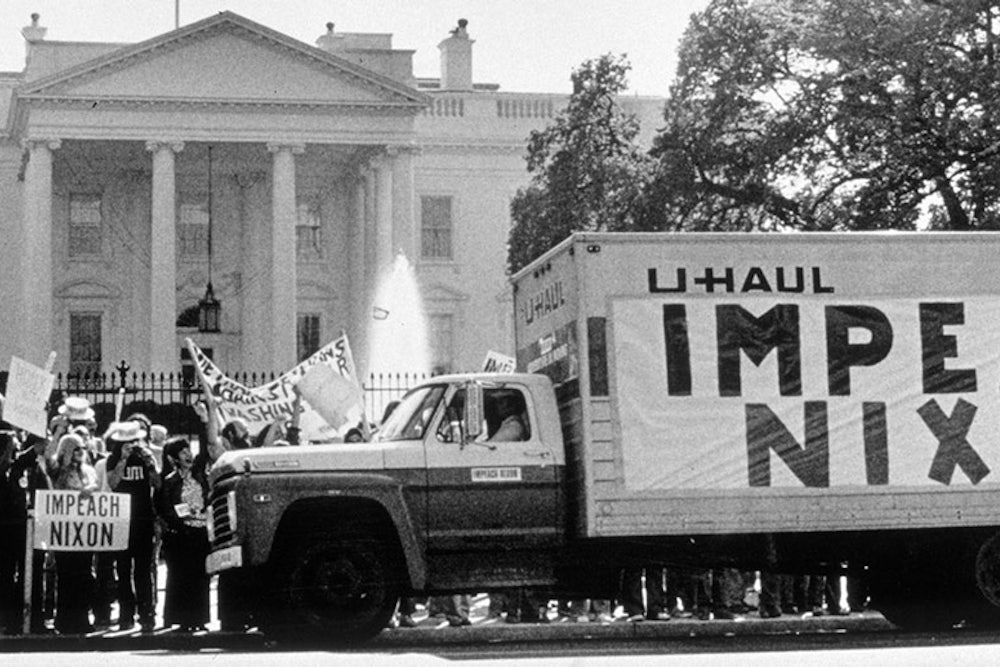

As history has shown, Nixon had reason to worry. His exchanges about China and the Soviet Union turned out to be well worth preserving—and Douglas Brinkley and Luke A. Nichter have assembled The Nixon Tapes, a book of transcripts of many of these conversations. (Only a fraction of the 3,700 hours of Nixon tapes have been transcribed and published.) Far more consequential, however, were the recordings of the innumerable hours Nixon spent covering up the abuses of power that had been threatening to surface since the arrest of a team of White House burglars at the Democratic Party’s Watergate headquarters in June 1972. Despite Nixon’s understanding that Watergate could doom his presidency, and despite a second directive to Haldeman to scale back the taping two weeks later, the machines continued to roll, and the existing recordings (except for those notorious eighteen minutes) were never destroyed. By that point the scandal had engulfed both men, and Haldeman—along with Dean and the domestic policy adviser John Ehrlichman—left the White House days later. Amid the chaos, Nixon’s order to modify the taping policy fell by the wayside. Historians—and the American public—have been the beneficiaries.

True to the prediction that he made to Haldeman, Nixon also failed to spend much time reviewing the tapes, even as he soldiered on with his cover-up for fifteen more months. “This proved a fatal mistake,” Dean writes in The Nixon Defense—fatal, Dean contends, because neglecting the tapes led Nixon to erect an untenable account of his role in the cover-up. (This is the “Nixon Defense” of Dean’s peculiar title—a bogus defense that ultimately failed.) Dean is on shaky ground in implying that had Nixon fashioned a more meticulous case for himself, based on immersion in the tapes, he might somehow have escaped impeachment: his crimes were too great to be saved by spin. Yet Dean is entirely correct that the tapes hastened Nixon’s undoing. Once their precise contents became known, even stalwart defenders deserted him in droves.

The tapes were also instrumental in Dean’s vindication. Enmeshed in the conspiracy himself, Dean chose in the spring of 1973 to cooperate with Justice Department and Senate investigators, sharing what he knew of the president’s participation. For a while, this confession created a public drama about which man was lying and which was telling the truth. But the tapes resolved the matter, and Dean deserves lasting credit for helping to bring Nixon’s criminality to light.

Now, on the fortieth anniversary of Nixon’s resignation, Dean has done what Nixon, for all his monomania, knew he could never do: listen to “all that crap,” make transcripts of the cover-up-related conversations, and write his own history of what happened. If for no other reason, Dean’s heroic labors of transcription make The Nixon Defense the most significant of the many Watergate-related books to appear during this anniversary year of Nixon’s resignation. Previous collections of transcripts, most notably Stanley Kutler’s Abuse of Power, which appeared in 1997, together contained, by Dean’s count, 447 Watergate conversations Dean has, with a team of assistants, made transcripts of the remaining six-hundred-plus exchanges. His book thus stands as the first chronicle of the cover-up to make use of all nine-hundred-plus recordings on the subject. This huge body of new evidence joins an already voluminous mass of material that encompasses dozens of memoirs, court records of the Watergate trials, the report of the Senate Watergate committee led by North Carolina’s Sam Ervin, Haldeman’s detailed diaries, and reams of White House paper. Together these sources enable Dean to plunge deeper than any previous account has into Nixon’s consuming obsession with Watergate during the year between the June 1972 break-in and July 1973, when the exposure of the taping system led Nixon to dismantle it.

It is hard to imagine who besides John Dean would have attempted a herculean endeavor such as this. It requires a zeal for thoroughness—and Dean, who opened his Senate Watergate testimony in June 1973 by spending seven hours somberly reading a 245-page prepared statement, is nothing if not thorough—as well as a desire to untangle every last Watergate thread, something that only someone whose reputation hinges on the episode’s historical interpretation could muster. But while Dean deserves praise for carrying out this feat, it is unfortunate that the work fell to an interested party rather than an objective outsider. Dean is still a man with a court case. His public persona and his post-scandal life have been shaped by Nixon and Watergate, and while he has summoned a great degree of dispassion in writing The Nixon Defense—it is fair, judicious, and for the most part soundly argued—the book bears the imprint of his idiosyncratic and personal quest to acquit himself and seal the verdict of Nixon’s profound guilt.

Dense and detailed at 746 pages, The Nixon Defense is alternately mesmerizing and mind-numbing. Its twists and turns are maddeningly hard to follow, and the chronological structure makes it easy to lose strands of the narrative. Dean’s account relies primarily on his transcripts, frequently rendering his story—as any record of spontaneous human speech is bound to be—elliptical, opaque, and full of confusing contradictions. And because Nixon and his gang obsessed about Watergate so much—one meeting between Nixon and Haldeman exceeded five hours—their remarks grow repetitive and tedious.

For all that, The Nixon Defense is an immensely valuable addition to the Nixon literature. Readers hardy enough to wade through it will find that Dean has unearthed a number of new shockers and delicious tidbits. We learn, for example, that in the summer of 1972, Ehrlichman met with Chief Justice Warren Burger to convey that Nixon wanted to prevent the halted trial of Daniel Ellsberg (who leaked the classified Pentagon Papers to the press) from resuming until after the presidential election. Then there is the news that when political pressure forced Nixon to name a Watergate special prosecutor in May 1973, one of the candidates was Warren Christopher—an appointment that, given Christopher’s fecklessness in his later public positions, might have altered history. We also learn that Nixon preferred Archibald Cox of Harvard Law School, who he thought would go easy on him. “Believe me,” Nixon told Al Haig, who replaced Haldeman as White House chief of staff, “if [Attorney General Elliot Richardson] would take Cox, that would be great.”

One of the most intriguing of these bits is an explicit pledge from Kissinger to Nixon to perpetuate the cover-up. It should be recalled that the first major abuse of power in the Watergate scandal was the decision in early 1969 by Kissinger and Nixon to illegally wiretap journalists and administration officials. Worried, as Watergate unraveled, that Kissinger might start blabbing, Nixon darkly reminded his aide of their shared complicity in Watergate’s earliest crimes. “As you know, Henry,” he taunted, “we did do some surveillance with the FBI on these leaks, you remember?” He wanted Kissinger not to flinch from their bogus claim that national security justified the taps. “Absolutely,” Kissinger obsequiously promised. “No, I will certainly not back off.”

More significant than any of these scattered disclosures, however, is Dean’s painstaking day-by-day picture of the president’s thinking during the first year of the cover-up—sometimes shrewdly political, sometimes angrily vengeful; here deluded in denying the severity of Watergate, there admitting it plainly. No other book has taken readers so close to the president during this critical year of his presidency, and Dean’s account confirms anew the depth and significance of Nixon’s involvement. Most critically, Dean finds Nixon himself admitting time and again, as the cover-up progressed, that he knew he was engaged in illegal acts.

Since Dean chose to come clean, history has treated him more kindly than Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Colson, and the other hooligans who joined and encouraged Nixon in abusing the power of his office. Owing to the televised Watergate hearings in the spring of 1973, many Americans will forever remember Dean as the reserved, earnest, slightly nerdy accountant-like figure whose impassively rendered tales of White House miscreancy directly implicated Nixon for the first time. He was a thirty-five-year-old pipsqueak taking on the president and his men, a young Republican David to Nixon’s Goliath.

But even then Dean was neither completely innocent nor entirely sympathetic. Though he had laudably tried to shut down the sweeping illicit “intelligence” operation proposed by G. Gordon Liddy that included the Watergate break-in, Dean nonetheless approved of many of the administration’s other pre-Watergate misdeeds. After the burglars’ arrest in June 1972, moreover, Dean readily served for nine months as the “desk officer” for the cover-up, and when he broke with Nixon, he was moved by self-preservation as much as by conscience. He served four months in federal prison.

In the decades since, Dean has striven both to prove that he was right and to make good. Researching and writing about Nixon and Watergate offered him a route to redemption as well as understanding. His first book, Blind Ambition (1976), one of the best of the Watergate memoirs, was a self-effacing self-portrait of a “meek, favor-currying” political Sammy Glick, drawn to the power and the glamour of high-level administration jobs, who lost his moral bearings in the miasma of Nixon’s White House. A quarter of a century later Dean wrote The Rehnquist Choice, his most scholarly effort, one of the only books to use the Nixon tapes not simply to shock or titillate readers but to reconstruct a narrative. In brisk prose it told the delectably politicized story of how Nixon placed his arch-conservative assistant attorney general, William Rehnquist, on the Supreme Court, transforming American jurisprudence.

If The Rehnquist Choice showed Dean at his most dispassionate—setting forth original research and a serious argument—his recent books have demonstrated a more strident disposition. Dean’s quest for absolution has also taken the form of calling out abuses of political power, as he did in a string of Bush-era polemics: Worse than Watergate: The Secret Presidency of George W. Bush (2004); Conservatives Without Conscience (2006); and Broken Government: How Republican Rule Destroyed the Legislative, Executive and Judicial Branches (2007). These books confirmed that Dean had grown more liberal in his politics, and like many liberals during the Bush era, he couldn’t help venting his outrage toward the president’s Nixonian abuses of power. Though Bush’s misdeeds certainly deserved censure, the newly fashionable genre of the political attack book is not an ennobling one for anyone. Especially regrettable was Worse than Watergate, if only because its title implied that Dean endorsed the then-fashionable (but profoundly mistaken) idea that Bush somehow did more harm to the republic than Nixon. Although Dean later explained that he meant to suggest only that Bush’s secrecy outstripped Nixon’s—though that claim too is debatable—it was plain that he had inhaled the contentious partisan ether of the new century.

Dean’s determination to vindicate himself, as well as his contempt for the far right, are understandable given the unremitting hatred directed his way by the Nixon camp since 1973, when he first cooperated with the prosecution. Initially, Nixon had hoped to minimize the damage his counsel would inflict, telling Haldeman on April 25 that he wanted to handle Dean “in such a way that he doesn’t become a totally implacable enemy.” Both men figured that if Dean fingered Nixon, it would be the president’s word against Dean’s, and, as Nixon said, “I don’t see the Senate or any senators starting an impeachment based on the word of John Dean.” But then, as Dean reports, Nixon voiced a fear. “Well,” he added, “except it could be he recorded his conversation.”

In fantasizing that Dean might have secretly taped him, Nixon was projecting. Nixon, of course, had secretly taped Dean. Especially damning was a now-infamous conversation on March 21, 1973, during which the president spoke cavalierly of raising hush money for the Watergate burglars. (Told that the burglar Howard Hunt was blackmailing the White House, Nixon, in typical amoral fashion, responded by asking, “How much money do you need? ... You could get a million dollars, and you could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotten.”) Sensing their own vulnerability, Nixon and Haldeman went from hoping to appease Dean to vowing to punish him—using the same violent word that Nixon used about the tapes: destroy. “Well, see, that’s the other way to destroy Dean,” Haldeman said to Nixon on April 25. Again on April 27, Haldeman urged the president to “go all out on a total basis to destroy Dean.” “He must be destroyed,” Nixon fumed to press secretary Ron Ziegler on May 8. Like the tapes, Dean was evidence incarnate of the president’s collusion in Watergate. Deep down, Nixon knew that the only chance he stood of ever being exonerated was for Dean and the tapes—incontrovertible testaments to his deceptions—to cease to exist.

The notion that Dean was a turncoat to be crushed became an article of faith among Nixon bitter-enders. It reached an absurd apex in 1991, when an incoherent, ill-sourced book called Silent Coup advanced the preposterous theory that Dean had planned the Watergate break-in because his girlfriend, Maureen Biner (now his wife of four decades), belonged to a call-girl ring frequented by Democrats. Promoted by Dean’s enemies, especially the lunatic Liddy—who had since become a right-wing radio host—this foul conspiracy theory won support from one or two blinkered historians, notably Joan Hoff, but within a few years it was completely discredited. But the allegations rattled Dean, who sued for libel and secured a settlement from the book’s publisher. Still, the Nixonian right continues to hound him. (The political consultant Roger Stone spent much of the summer hectoring Dean in the conservative media.) These experiences seem to have injected a certain defensiveness into Dean’s writing. The rational world knows that Nixon’s “defense” was completely bogus, but Dean—haunted and taunted by the flat-Earth crowd—is still pressing his case as if it were 1973.

Dean’s participation in the events of 1973 not only explains the high sense of mission that infuses this book but also colors his account in other subtle ways. He remains keen to settle scores, passing up few opportunities to slam John Ehrlichman in particular. He reminds us that Ehrlichman was “convicted of more crimes than anyone save Liddy,” and that Ehrlichman’s self-protection “had been driving much of the cover-up.” Dean also includes a racist rant from the tapes in which Ehrlichman says that blacks should “all be stuck in boxcars [and] sent around to one in each town” to work as domestics, to dilute their political power.

Personal experience also leads Dean to focus narrowly on the first year of the cover-up—Dean’s own final year working for Nixon, and the year he metamorphosed from conspirator to whistle-blower. In a straightforward memoir, this choice would be justified; as history it is problematic. Putting the cover-up at the center of his tale—as opposed to the abuses of power that were covered up—Dean in effect endorses the dubious Washington wisdom that the cover-up is worse than the crime. But with Watergate, that canard is plainly false: Nixon oversaw a long train of severe offenses that, quite apart from the cover-up, warranted his impeachment and removal from office. Indeed, Dean himself provides some enticing glimpses into the depth of White House mischief, some of which remains cloaked in mystery even today. Tantalizingly, Dean quotes Colson telling Nixon and Haldeman in October 1972 about his undiscovered black deeds: “The things that I have done that could be explosive in the newspaper will never come out because nobody knows about them. I don’t trust anybody in my office.” Again in January, Colson tells Nixon: “I did things out of Boston, we did some blackmail. ... I’ll go to my grave before I ever disclose it. But we did a hell of a lot of things and never got caught.” Lamentably, The Nixon Defense provides no clear narrative or overview of the multiple pre-1972 crimes that the cover-up was designed to keep from public sight.

A broader focus on Watergate as a whole, instead of just the cover-up, would also have prompted Dean to highlight certain aspects of his story that he leaves only implicit. One conclusion that emerges from Dean’s pages—though he does not emphasize it himself—is how ineffective and even corrupt the Justice Department’s investigation of Watergate was for much of its first year. While Liddy, Hunt, and the burglars went to trial, it took much longer for prosecutors to indict Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Colson, and other big fish. One reason why the Justice Department lagged, and why a special prosecutor was ultimately necessary, was—as The Nixon Defense makes clear—the person who led its criminal division, Henry Petersen.

Throughout late 1972 and 1973, Petersen regularly briefed the White House, via Dean, about the ongoing investigation. Petersen’s behavior has been known for years, but he always claimed that he never suspected Dean was helping to coordinate the cover-up, and for the most part the news media and historians have granted him a free pass. Yet The Nixon Defense shows that Nixon, for one, believed that Petersen “basically cooperated with Dean in the cover-up” and that, if nothing else, the president and his top aides relied on Petersen’s updates and trusted him not to betray them.

The White House’s unholy relationship with Petersen began early on. “Petersen’s been very good with Dean ... ,” Ehrlichman told Nixon in July 1972, “keeping Dean informed of the direction things are going.” The collusion continued for months, and in his all-important hush-money conversation with Nixon on March 21, 1973, Dean reminded the president: “Petersen’s a soldier. He kept me informed. He told me when we had problems, and the like. He believes in you. … I don’t think he’s done anything improper, but he did make sure the investigation was narrowed down to the very, very fine criminal things, which was a break for us.”

Amazingly, even after Dean came under suspicion, Petersen continued to deliver updates to the White House—only now to Nixon himself. In a meeting on April 17, Nixon felt Petersen out. “I don’t want you really to tell me anything out of the grand jury,” the president said, taking the high road as an opening gambit, “unless you think I need to know it.” Then, probing further, he asked, “I guess it would be legal for me to know?” Petersen replied, “Well, yes, I think it is legal for you to know.” A short while later Nixon was opening up, urging Petersen to wrap up the whole Watergate investigation before it ensnared anyone new. “I’d like to get the God damn thing over with.”

Within a few days, the men developed a greater ease with each other. One moment of unintentional comedy in The Nixon Defense comes when the president, now talking to Petersen as if he were just another co-conspirator, begins to divulge, seemingly without reflection, the burglary of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office by his team of White House “plumbers.” Nixon explains to Petersen, delicately, that after J. Edgar Hoover refused to unleash the FBI on Ellsberg, “an investigation was undertaken with a very, very small crew at the White House.” Then, suddenly realizing that he had shared highly incriminating information with a federal prosecutor, Nixon added—entirely falsely—that “it was a national security investigation, ... not related in any way to the Watergate thing.” As was his wont, Nixon was protesting too much. But Petersen signaled that he had nothing to fear and complaisantly asked to know about other such White House operations, because “I can’t stay away from that which I don’t know.” Still trying to ward off Petersen, Nixon insisted once more that “I want you to understand that I have never used the word ‘national security’ unless it is.”

Moments later, though, Nixon had another turn of heart. Like a confident gambler, he informed Petersen about his March 21 hush-money conversation with Dean—in hopes of discrediting Dean’s account in the prosecutors’ eyes. Lying once again, Nixon told Petersen he’d rebuked Dean, “You can’t go down this road, John.” Sensing Petersen’s mortification at the whole story, Nixon then backpedaled. “Forget what I just told you,” he demanded. Although Petersen, under pressure from the prosecutors in his own office, soon stopped sharing knowledge with the White House, conversations like these suggest that he had done much along the way to undermine his own investigation.

Discoveries such as these—about Petersen, Colson, Kissinger, and many others—lie buried amid the meandering and repetitive conversations of The Nixon Defense. Dean has chosen not to flag his best finds, so that to appreciate the book fully a reader has to come to it already knowing an enormous amount about Watergate and what has been previously written. Even then, one feels like a prospector for gold, shaking and sifting the pan in hopes of detecting precious nuggets.

Even to the lay reader, however, it will be apparent that of the many conclusions to be drawn from Dean’s heaps of transcripts, the most important concern Nixon himself. In its accretion of comments and exchanges, The Nixon Defense confirms how early and enthusiastically the president was directing the cover-up. Not only was Nixon trying to snuff out the FBI investigation in June; not only was he authorizing the payment of hush money within a few weeks’ time; he also knew from the start about early decisions by top White House aides to commit perjury to keep the scandal from spreading. He was fully complicit all along.

Nixon in effect admitted this in his memoirs, if grudgingly. What The Nixon Defense highlights, as other books have not, is that Nixon was unmistakably aware of what he was doing. “We will cover up until hell freezes over,” he tells Al Haig at one point, long after the charade had begun to crumble. As a rule Nixon was cagey, always on guard; and knowing he was being recorded, he was circumspect when addressing his own guilt. But when you have tape machines whirring for all your working hours, there is simply no way to keep your guard up at every moment, and in the sheer yardage of tape that Dean has listened to and serves up here, he catches Nixon more than once dropping the posturing and confronting his culpability.

In mid-April 1973, for example, Nixon talked with Haldeman and Ehrlichman, who acknowledged their involvement in the cover-up. Responding in kind, Nixon let loose. “Well, I knew it, I knew it,” he said, dispensing for a moment with any pretense. Then, apparently remembering the tape recorders, he added, “I knew. I must say, though, I didn’t know it.” But that clumsy effort to retract his admission couldn’t alter what Nixon knew to be true. Two months later, he let his guard down again, this time to Colson. “You see, they were right, in a sense,” he said. “There was a cover-up, let’s face it.”

Similar admissions of guilt periodically pop out of Dean’s reams of conversations. Speaking about the so-called Huston Plan to create a secret White House intelligence unit, Nixon tells Haig: “I ordered that they use any means necessary, including illegal means... The president of the United States can never admit that.” Another time, also speaking to Haig, on the subject of executive privilege, he affirmed that “if Haldeman’s conversations with me ever get into the public record, it will bring the house down.” And on still another occasion, speaking to his speechwriter, Ray Price, Nixon took responsibility for all his underlings’ misdeeds: “Hell, I appointed Mitchell, I appointed Haldeman, I appointed Ehrlichman, I appointed Dean and Colson. These are all my people. If they did things, they did them because they felt that’s what we wanted. And so I’m responsible.”

But when Nixon wanted to, he could revert to disingenuousness. At a May 10, 1973 Cabinet meeting that Dean describes, he discussed the recent personnel shake-up brought on by the latest Watergate disclosures. Trying to reassure his team, he told them that the most recent scandals would “fifty years from now be just a paragraph, and a hundred years a footnote.” Wrong. We are now forty years on, and Watergate has not been displaced as the overriding legacy of Nixon’s presidency. Nixon hoped that as time passed, he would look better and better; in fact, he has come to look worse. Having failed to destroy the tapes, having failed to destroy John Dean, they instead came back to haunt him. As Nixon acknowledged in another eruption of candor, the only one he ended up destroying was himself.