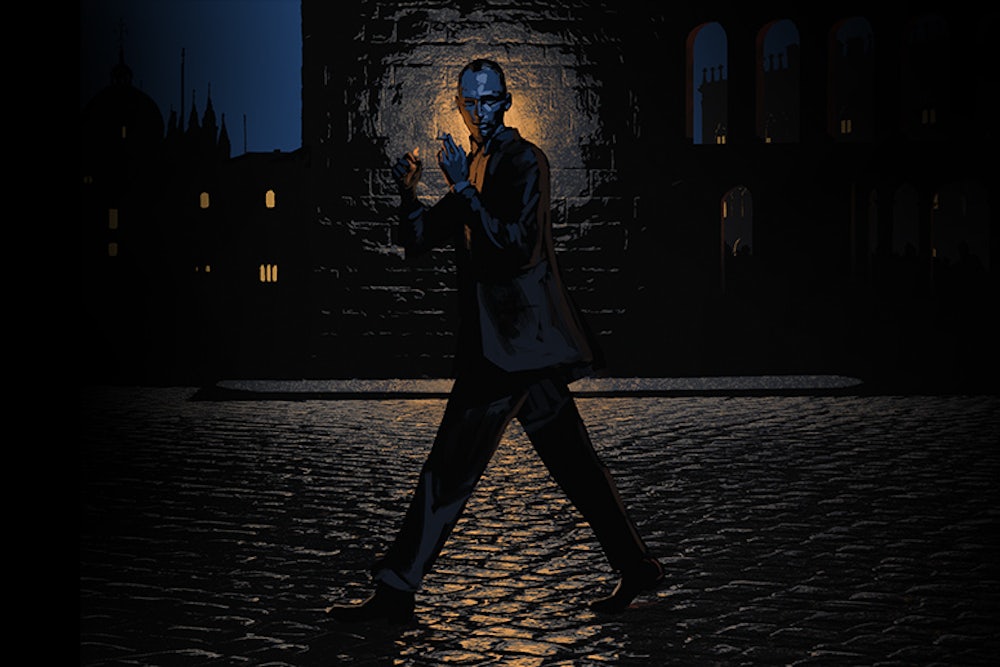

Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, translated by Len Rix (New York Review Books)

This fall Journey by Moonlight, a beloved Hungarian classic first published in 1937, will at last make its American debut. It is difficult to say whether the book is happy or sad, or both, or neither. It is above all strange, a brief reprieve from the logic according to which happiness and sadness are opposed to one another. The masterwork of Antal Szerb, a celebrated Hungarian man of letters who is practically unknown in the English-speaking world, Journey by Moonlight follows a malcontent Hungarian businessman, Mihály, and his new bride, Erzsi, on their honeymoon in Italy. Though Mihály has resigned himself to a petty bourgeois existence, taking a position in his father’s firm and marrying a sobering and practical woman, he finds himself entranced by the Italian countryside—its aura of historical gravity, its savage beauty, and the offer of madness and magic that its tangle of close, crooked backstreets seems to extend. Erzsi, a symbol of the chaste respectability that Mihály finds himself increasingly unable to stomach, quickly becomes a burden, and when Mihály accidentally on purpose—he isn’t sure, and we aren’t sure—boards the wrong train, abandoning his new bride in a compartment bound for a different city, he frees himself of his ties to Hungary and heads to Siena in headlong pursuit of something wild, romantic, and fundamentally ineffable.

Like any good fugitive, Mihály remains on the move, traveling from one city to another. At times he is exultantly happy, feeling that he has succeeded in escaping his dreary middle-class origins and oppressive Hungarian commitments. He is stubbornly dismissive of details such as money, insisting that they smack of baseness, and we feel that he has succeeded in renouncing his former life. At other times, however, he cannot but confront the reality of his abject poverty—his shabby attire, his seedy lodgings, his cheap unsatisfying fare. Time and time again, Mihály’s lofty goals come into direct conflict with the indignity of his material circumstances.

Mihály’s pursuit is subject, in turn, to its own pursuit: Journey by Moonlight has the frantic quality of endless flight, and Mihály has the harrowed quality of someone looking constantly over his shoulder. We feel that his responsibilities threaten to bear down on him at any moment, that his freedom and his romanticism are just seconds away from caving under the pressures of his father’s demands, Erzsi’s unrelenting pragmatism, and his dwindling finances. Yet Mihály is in equal measure a pursuer: he hunts out the answer to a question that he remains unable to pose explicitly—an answer so definitive, so satisfying, that it clarifies the question.

Szerb’s novel, with its surreal dissociated prose, its stormy vistas and towering turrets, has a similar effect on its readers. Often it reads like a honeymoon—sometimes even a honeymoon from a honeymoon, an escape from an escape—but at the heart of its appeal is a sense of fragility, of unsustainability. It grants its reader a brief reprieve from the temporal constraints of normal life, proceeding in a series of fits and starts as erratic as Mihály’s ecstasies and despairs—only to return us unceremoniously to the confines of Mihály’s dingy room. Everywhere we come up against everything that we ran away to escape.

But even here—especially here—there is something heartening. For Szerb, each defeat is a chance to prove that there is something even more worthwhile, even more anathema to bourgeois practicality, than normal hoping. And that is hoping impossibly.

A Catholic of Jewish descent and a professed anti-fascist in World War II Hungary, Szerb had ample opportunity for impossible hope. He was born in Budapest in 1901, the child of middle-class Jewish converts, and he quickly proved himself something of a wunderkind. “It all began ... ,” he once wrote, “or rather, it never really began, because I always read and wrote, almost from the moment I was born (I was the spectacled kind of baby).” Fluent in Hungarian, English, German, and French, he received his doctorate in German and English literature from the University of Budapest in 1924 at the age of 23. Only ten years later, with an almost disgustingly impressive litany of scholarly and literary achievements to his name, he was elected president of the Hungarian Literary Academy. Four years later, he was appointed professor of literature at the University of Szegad. A mere eight years after that, he was removed from his position at the university, beaten to death in a forced labor camp in Balf, and buried in a mass grave.

Despite his tragically short life, or, we might think, to spite it, Szerb’s literary legacy is prolific. One of his short stories, “The Incurable,” depicts an author of astonishing productivity. When he is asked when he finds the time to write so much, the author replies: “You should really be asking, when do I not? I fall asleep writing, and wake up writing. I plan my hero’s fate in my dreams, and the moment I open my eyes the signing-off phrase for my radio broadcast comes into my head.” “And when do you live?” replies the interlocutor. “Never,” the writer responds. “I’ve no time for sport, and none for love. For years the only women I’ve spoken to have been the ones bringing manuscripts, and believe me, they aren’t the most congenial. But that’s not the real problem. The problem is finding time to read.”

Szerb may as well have been describing himself. In a mere 44 years, he managed to produce three major scholarly studies—An Outline of English Literature (1929), History of Hungarian Literature (1934), and the multi-volume History of World Literature (1941)—an abundance of essays, translations, and reviews, a handful of novellas and short stories, and four full-length novels. There is also One Hundred Poems, a multi-lingual anthology of canonical Western poems that Szerb compiled in implicit defiance of the Axis powers and their distaste for certain kinds (the kinds that were not radically pro-German) of multiculturalism. The work was a monument to the international literary tradition that Szerb loved so much, a quiet but powerful act of protest.

For Szerb, literary protest was the most—the only—powerful kind. He was obsessively, even maniacally academic, and in a world of uncertainty and inconstancy—a world that threatened to collapse at any moment under the weight of fascism and the ever-increasing pace of technological progress—literature alone was enduring, a testament to all that was permanent in us. In a delightful short story titled “Musings in the Library,” he wrote: “Moods and desires come and go, like so many restless tourists, but the folios remain in place, waiting benignly to be read by succeeding centuries. Buses, taxis and metros rush us about at frantic speed; placards bawl out every grubby little change in our material lives: the library stands for what is pure and true.”

Literature, for Szerb, was an antidote to the poisonous vicissitudes of modernization, and the literature that he produced was literature unto literature, literature about literature, literature for literature—a jumble of literary literatures, a eulogy for itself. His works present literariness—a literary disposition and everything that goes along with it, more than the content of any particular book—as an alternative to life in its habitual dreariness. Where life is ploddingly predictable, literature is exhilarating, packed with action and intrigue; where life is transient and unreliable, literature is eternal; where life is essentially middlebrow, a series of small indignities and empty pleasantries, literature is profound and affective and immense, huge and horrifying and excessive, prodigious and penetrating and significant. To be impractical and ill-suited to this boring, banal world was, in Szerb’s eyes, the highest possible achievement. “The practical career is a myth, a humbug, invented to cheer themselves up by people who aren’t capable of doing anything intellectual,” a professor in Journey by Moonlight pronounces.

In keeping with this doctrine, Szerb’s novels and stories proudly proclaim themselves literary. They make no effort to mimic reality: we have enough of that. Instead they are all castles and secret passageways, family legends and occult orders. They take obvious pleasure in conforming to the demands of their genres, in half- parodically and half-seriously embracing conventions, in launching assault after assault on the twin institutions of the practical and plausible.

In Szerb’s first novel, The Pendragon Legend, a charming neo-Gothic tale set in a decrepit Welsh castle, the characters almost go so far as to explicitly acknowledge their status as fictions: “In all the books I’ve read,” one captive muses, “when it gets to this point the captives try to think of ways of escape.” Szerb’s characters proceed, of course, to try to think of ways of escape. (And, as the logic of the neo-Gothic demands, they succeed.) The Pendragon Legend is theatrical. The book seems staged for our benefit—and for the benefit of its characters. The protagonist, János Bátky, a scholar of alchemy and the occult, stumbles into a medieval Welsh town where the sorcery that he studies comes true and the myths that he has read come to life. Like Bátky, we are initially skeptical, but soon we align ourselves with the fiction, hoping that Szerb will refrain from proffering a rational explanation. He does not disappoint.

The work, written in 1929 during Szerb’s post-doctoral fellowship in London and published in 1934, would be overblown if it took itself too seriously, but it is not heavy-handed. It features resurrections, a sprinkling of dark magic, and a few staples of satanic ritual—but it is unfailingly playful, subtly ironic, a self-mockery peppered with compelling flashes of earnestness and insight. “What a shame,” Bátky observes, “that those moments when man is noble and pure and akin to the gods are so transient, so fleeting, while that complicated nonentity the Ego is always with us—of which one can only speak in terms of protective tenderness and gentle irony.”

Szerb took his character’s remark to heart. His love affair with literature was passionate, intense, and serious, but for all that it was never humorless, and it never lost the flirtatious and giddy quality of an adolescent crush. Reading Szerb on literature—reading Szerb at all—is like watching a lover dote on the object of his affections. In “Musings in the Library,” the narrator becomes infatuated with a fellow library-goer, noting that “books are the most potent aphrodisiacs.” “Taking you through those books, into my personal domain, my little empire––it was almost as delightful as initiating a virgin into the secrets of love,” he tells her. In a similar scene, in another library in The Pendragon Legend, an aspiring scholar calls her romantic interest “her prince transformed into a reference book”—the highest praise, by Szerbian standards.

There is something touching—something believable—about a love so variable, a romance that operates both at the level of profound passion and delighted amazement. Szerb was consumed by literature, maddened by literature—but he was also amused by literature, enlivened by literature, and, occasionally, delivered by it. “I expected something from literature, my redemption, let’s say,” he wrote. He continues: “I spent my entire youth in a happy purgatory, because I always felt that within minutes I would understand what I hadn’t understood before, and then Beatrice would cast off her veil and the eternal city of Jerusalem would reveal itself to me.” If understanding came at the cost of academic complacency, of no longer wooing and wishing after whatever impossible intellectual fulfillment that Mihály left Erzsi to find—well, then it wasn’t worth it. Szerb’s love has much in common with the courtly romances that so many of his dreamy protagonists long for: its object is fundamentally, tantalizingly, magnificently unattainable.

Borges famously remarked that “I have always imagined that paradise will be a kind of library.” For Szerb, a library was not quite paradise: it was nothing quite so static, nothing quite so stable. A library was a purgatory that was also a blessing, an ongoing act of learning without satisfaction, cease, or salvation. And perhaps, for Szerb, paradise and purgatory were one and the same: paradise consisted only in a voracious appetite for knowledge that could never be sated, in never finding oneself in the miserable position of having nothing good to read.

Most of life’s problems, for Szerb, amounted to having nothing good—nothing sufficiently challenging—to read. Fascism was no exception. When Szerb went on vacation in Italy in 1936, the population that greeted him seemed happy and healthy. “I am struck by how cheerful, how proud and friendly they are,” he wrote in his journals. “Yes, it’s all very wonderful, and wonderful the countless social achievements of Fascism.” But he was still suspicious. “Is it not enough, then, to live as man was meant to? Or is it also necessary to be ‘happy?’ Who is happy? The madman, the drunk, the subject of hypnosis or of auto-suggestion. Man in his natural state is dissatisfied. Anyone who is not should be treated with suspicion.”

In Szerb’s estimation, fascism was an intellectual problem: a failure of the intellect and the imagination, essentially a problem of complacency. The Italians had reconciled themselves to the world as it was—and this, thought Szerb, was their monumental mistake. The solution, like all non-palliative solutions, was literary: literature alone could instill in us an insatiable hunger for an extraordinary world just beyond our reach. It is the disparity between literary perfection and drab actuality that motivates us, in Szerb’s view, to improve our world, to question its assumptions and tear at its established fabrics. For Szerb, there was almost a moral imperative to rise to the challenge of a good book: “anyone who loves books cannot be a bad person,” a character in The Pendragon Legend muses.

But literature and its ethics, which may have redeemed Szerb, could not save him. In Journey by Moonlight, Mihály contemplates suicide: unable to reconcile the world of his imaginings with a comparatively bankrupt reality, he resolves to take his own life. The act that he plans is a radical rejection of a world that demands we submit to its tedium. Mihály is choosing between existential methodologies, and he chooses the method of melodramatic gesture over the method of a long, dull enduring. Still, there are limits to Mihály’s escapism. He recognizes, ultimately, that navigating this tension, living within a diametric opposition, is his due—that human existence is in fact the long, fraught negotiation of literature on the one hand and daily life on the other. There is nothing precious about Szerb’s cult of literature. His eyes are trained on the actually existing world. “He would have to remain with the living. He too would live: like the rats among the ruins, but nonetheless alive.” Yet he was a great foe of “realism.” Even at the horrible intersection of hope and its disappointment, Mihály persists in hoping, impossibly, that life will someday live up to its literary analogue—because, after all, “while there is life there is always the chance that something might happen ...” With those words this bleak novel optimistically concludes.

Life did not allow Szerb to verify his hope. In “The Incurable,” the prolific author proclaims defiantly that “if you threw me in prison, I’d write in blood on my underwear.” Szerb did not know how prophetic these words might prove. In his last letter, he wrote to his wife:

In general, the place where we are now, Balf, is awful, and we are in dire straits in every regard. I have no more hope left, except that the war will end soon; this is the only thing that keeps me alive. It is getting dark now and I am really not in the mood to write more.

He died with fragments of the One Hundred Poems—and his shattered spectacles—in his coat pockets. The product of all those beautiful, carefully chosen words was, finally a horrific, brutal silence. The world prevailed over literature after all.

But not forever. Journey by Moonlight is a beautiful book, the sort of book that stays imprinted on some soft part of you for a long time. Its intelligence is so humane—so forgiving to the last. It doesn’t shirk the task of exposing our hypocrisy, how much follow-through we lack, how incapable we are of changing—but even so, with almost unaccountable stubbornness, it holds out some hope for us. It acknowledges and accepts the monotony of life, but not for a moment is it ever resigned. This is a quickening, re-vivifying book. There is something behind the brilliance of its narrative, something beneath its clever construction, that bespeaks a very real grasp of the anxieties, the inconsistencies, the akrasia that characterize every human heart, at its intimate core.

“Some miraculous preexisting harmony,” Szerb remarked in his journal, “seems to operate in the human soul: an architect is born in Italy and creates certain works so that two hundred years later a poet can arrive from Germany and, through those works, come to understand himself and his destiny. Meanwhile, in all that time, how many nations, and how many generations, have annihilated one another! Mihály Babits is right when he tells us: ‘Great minds call to one other across time and space.’ ” And from the wreckage of the Holocaust, from such horrible annihilation, from such a violent silencing of so many voices, this extraordinary novel emerges as another improbable survival.