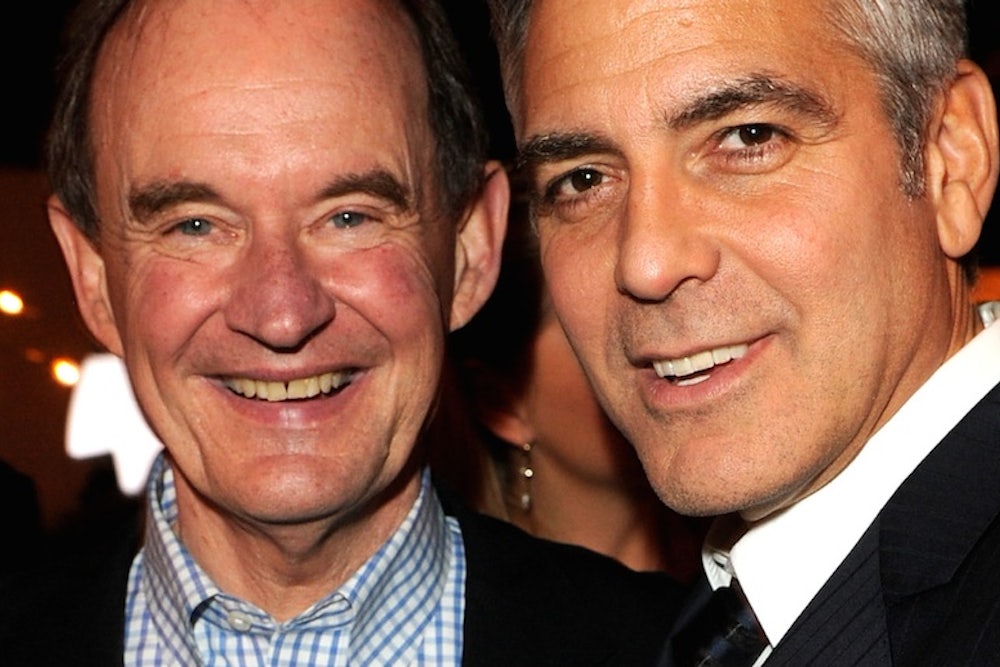

David Boies has spent much of this year putting the celebrity in celebrity lawyer. In January, he and Ted Olson, his onetime Republican antagonist from Bush v. Gore days, were at the Sundance Festival for the premiere of “The Case Against 8,” a documentary about their crusade against California’s anti-gay marriage law. In May, they enjoyed the spotlight anew with the release of Forcing the Spring, Jo Becker’s book about the swift advance of same-sex marriage, which holds them up as heroes of the movement. In May, they even made an appearance on the New York Post’s Page Six after they did a film promo event in the Big Apple: “Ted Olson and David Boies Become Movie Stars For a Night.”

As the glitter has been swirling, though, Boies has been busying himself with a far less celebrated and less Hollywood-ready case called Starr International Co., Inc. vs. United States. In that case, which goes to trial next week, Boies is representing former AIG CEO Maurice “Hank” Greenberg and his new firm, Starr, in their lawsuit alleging that the federal government’s bailout of AIG in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis represented an illegal taking from AIG’s shareholders. The lawsuit, filed with the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in Washington, is seeking as recompense from the government the tidy sum of $40 billion.

The case, which goes to trial on Monday, is considered a long shot by many legal experts, who note the audacity on Greenberg’s part: he is asking U.S. taxpayers to shell out billions more on top of the $85 billion the government already deployed back in 2008 to prevent the collapse of a company that Greenberg and other AIG executives had driven to the brink with a reckless immersion in the business of underwriting credit-default swaps. A verdict in Greenberg’s favor, it turns out, may actually have to be paid out by AIG, not the U.S.

But the case is already costing U.S. taxpayers a considerable sum even in advance of any potential payoff to Greenberg. The case has turned into the ultimate legal morass, with a docket of filings and hearings at the Court of Claims that has grown to nearly 300 items, more than 70 depositions, and an exhibit list that runs to more than 4,600 items, the majority of them from Starr. All told, the case has produced more than 36 million pages of documents. The government has had a dozen lawyers working more or less full time on the case for more than a year. And the trial promises to be a bear, with the two sides planning to call as many as 117 witnesses*—including former Treasury secretaries Henry Paulson and Tim Geithner and former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, who will be put publicly under oath for the first time to answer questions about the bailouts. The trial is scheduled to run at least six weeks.

Boies has gone along for the ride—literally so, as he’s gotten to take flights on Greenberg’s private plane, not to mention raked in countless hours at his top-dollar rate. His rate is reportedly more than $1,200 an hour, though as a 2011 article explained, “more often his deals with clients involve alternatives such as pegging fees to his success.” He reputedly received $100 million for representing Greenberg in another AIG-related case in 2009. That he is now profiting far more from his 89-year-old vengeance-seeking client has more than a few in the financial and legal world criticizing Boies’ participation. Yes, every man deserves his day in court. But a lawyer can also let his client know when his desire for an emotionally-satisfying showdown simply doesn’t have much chance in court. Instead, Boies’ representation—both through his sheer reputation and his indisputable skill—has given Greenberg’s crusade more staying power than it otherwise would have had.

“No one ever writes about what [Boies] really makes his money on. He has got a huge firm with a lot of names on the masthead, and it’s not a pro bono firm,” said Dennis Kelleher, a former top Senate Democratic aide and litigation partner at Skadden, Arps, who now runs a pro-financial reform group called Better Markets. The AIG case, Kelleher continued, “is an outrageous example of ‘no good deed goes unpunished’ and second-guessing.” Boies, he said, “is a great lawyer and makes great arguments but the country better hope he doesn’t prevail. This crisis cost the economy $12.8 trillion in total [according to a Better Markets analysis] and then on top of that, David Boies is arguing that the U.S. taxpayers should send them checks because the U.S. taxpayers bailed them out from their reckless debts?”

The Greenberg case is not the only one that Boies, who did not comment for this piece, has brought against the government over its handling of the crisis. He is representing one of several groups of shareholders of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac protesting that they were given short shrift by the federal takeover of those companies. In fact, there are so many investors trying to make claims over Fannie and Freddie that Boies, Olson, and the lawyer they vanquished on Prop 8, Charles Cooper, are all representing clients on that front, mostly hedge funds who took stakes in the companies after the writing was already on the wall. “Where’s the victim?” says Kelleher. “These are the biggest financial players in the country placing bets at the expense of taxpayers.”

But it’s the Greenberg lawsuit that really takes the chutzpah award.

A quick refresher: Under the leadership of Greenberg, AIG moved to profit from the housing boom of the last decade by building a highly lucrative side-line in issuing credit-default swaps to protect banks against credit losses on collateralized debt obligations assembled from mortgages of dubious provenance.* With the bursting of the housing bubble in 2007 and early 2008 and the ensuing collapse of financial markets in September 2008, AIG was faced with massive payouts—under its contracts, it was required to post billions of dollars in collateral on swaps it had insured that were now plummeting in value, and to return billions in cash to counterparties. With financial markets frozen, the company could find no way around its liquidity crunch. Bankruptcy for AIG would have been catastrophic for the global economy—the company, with more than 100,000 employees, not only owed vast sums to the teetering banks, but was enmeshed in countless more conventional insurance contracts around the world.

A last-minute attempt to assemble a rescue by other financial giants came to naught. The government, led by then-Treasury Secretary Paulson and then-New York Fed President Geithner, stepped forward with an emergency loan that came with tough terms—14 percent interest and a 79.9 percent equity stake for the government. After some debate, the AIG board voted to accept the bailout. Over time, the government provided AIG with more than $180 billion in support. The bailout came under scrutiny because of the government’s controversial decision to pay AIG’s counterparties (including Goldman Sachs) 100 cents on the dollar. Still, the rescue worked so well that, by the time the government sold its final stake in 2012, it netted taxpayers a profit of $23 billion.

Greenberg, a Bronze Star recipient in World War II who built AIG into the world’s largest insurer over the course of his nearly 40-year tenure as CEO, was no longer at the company’s helm at the time of the bailout, though he and Starr remained a major shareholder, with a 12 percent stake. He had been forced to resign in 2005 amid then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s relentless investigation into alleged fraudulent accounting to inflate the company’s financial standing, the aftershocks of which will have Greenberg standing for a civil trial in January.

The loss of his perch at AIG, and its subsequent bailout, has been a searing experience for Greenberg, whose firm did not respond to comments for this piece. Among other indignities, he has fallen off the list of the very wealthiest men in the world. To reclaim some lost glory, he has tried to replicate some of the Chinese-themed interior design of its executive office and dining room (the company’s origins are in Shanghai) at Starr’s office in Manhattan, say those who have been inside. And in November 2011, Starr filed suit over the AIG bailout. Boies is arguing, essentially, that the government exacted an unconstitutional taking from AIG by demanding such a large equity stake, simply for the sake of publicly punishing the company, at a time when AIG was faced with no other option but bankruptcy. At points, Boies has all but suggested that Geithner and Paulson were engaged in a conspiracy to take over AIG and have been seeking to cover it up ever since. “The government is not empowered to trample shareholder and property rights even in the midst of a financial emergency,” the lawsuit stated.

The government counters that Starr can’t claim an economic loss from the bailout given that its stake in the company is of far more value now than if AIG had gone bankrupt. It notes that Congress delegated broad authority to the government during the crisis, including authority to require equity stakes as part of bailouts. Most of all, it stresses that there was no illegal taking because AIG’s board supported the bailout and, early last year, voted against joining Greenberg in the lawsuit. “Because the very actors whom Starr alleges were coerced have uniformly testified that, in fact, they were not, there is no triable issue as to whether AIG voluntarily accepted the rescue,” the government stated in its July motion to have the case dismissed before trial. “This is fatal to Starr’s equity claim.”

In his response, Boies argued that the AIG board’s approval of the bailout terms did not make them legal, given the duress the board was under. “Where the Government conditions the conferring of a benefit on a citizen surrendering property the Government is not authorized to demand, the citizen’s agreement is not a defense to an illegal exaction claim,” he wrote. The government’s retort to this bordered on the incredulous: “Under Starr’s theory, the Government was required not only to offer to rescue AIG with better terms than AIG could find in the marketplace, but to confer an enormous windfall on its shareholders by ensuring that they gained every benefit from the taxpayers’ support.”

Already, a federal judge and appeals court have tossed out another version of the lawsuit, against the New York Fed. U.S. District Judge Paul Engelmayer of the Southern District of New York rejected Boies’s claims out of hand. It was absurd to suggest, Engelmayer wrote, that the New York Fed had pulled off an “act of Napoleonic plunder” in providing a high-interest bailout loan, or that it had exerted a conspiratorial influence on AIG’s board in an act of “government treachery worthy of an Oliver Stone movie.” “Far from describing actual control of AIG by an outside party, [Starr’s] allegations describe a moment of corporate desperation, in which AIG’s Board grabbed the sole lifeline extended to the company,” Engelmayer wrote. “Merely because the AIG board felt it had ‘no choice’ but to accept bitter terms from its sole available rescuer does not mean that that rescuer actually controlled the company.”

Legal experts I interviewed describe Starr’s case as a Hail Mary. It’s a serious stretch, they say, for Greenberg and Starr to claim that just because the government treated other financial institutions differently during the crisis that it had no right to treat AIG as it did. If that were the case, there would be an endless stream of cases every time some person or company was treated less favorably in a government taking than someone else was. And that’s not even getting into the broader historical context of the financial crisis. The government was taking these actions on the fly, trying to prevent a catastrophe. Should a court, six years later, really be second-guessing those decisions, in favor of one of the people who helped give rise to the crisis in the first place? “Greenberg … created the culture that created the risk-taking that brought AIG to its knees, and that I think is unforgiveable,” says James Cox, a business law professor at Duke University.

But a judge in the relatively obscure, conservative-leaning Court of Federal Claims, Thomas Wheeler, accepted the case and is giving the distinct impression that far from being concerned about what a morass it has become, he is reveling in it. In his recent ruling against the government’s motion to have the case dismissed before trial, Wheeler essentially argued that the case needed to go to trial because it had dragged on as long as it had and produced a lot of paper. “The bulk of the evidence presented serves to demonstrate the need for a trial,” he wrote. “The sheer volume of material presented is a testament to the complexities of the issues before the Court.”

So to trial we go. Boies—whose prowess as a lawyer is all the more remarkable given that he is severely dyslexic—has reserved his team a floor at the grand Willard Hotel for the duration of the trial, around the corner from the courthouse. A preliminary hearing earlier this month brought out no fewer than a dozen lawyers—seven for the government, and four alongside Boies. The Starr team came across as more confident—while the government’s lawyers huddled together to chat seriously before the hearing began, the Boies team was quiet and relaxed. Once the hearing started, it was clear that the government’s lead lawyers, Kenneth Dintzer and Joshua Gardner, were no match for Boies’ gravitas. Wheeler was jovial throughout the hearing, furthering the impression that he is tickled to be in the midst of this drama. He cracked a few jokes, including one, while deciding whether to allow real-time transcription services, that the “trial that may have some initial attraction but I wonder how high the ratings are going to be after a while.”

The American taxpayer who is footing the bill for more than half of this spectacle surely finds such humor side-splitting. Starr v. U.S. looks like a classic example of what my colleague Noam Scheiber wrote about earlier this year, the way in which our gaping income inequality is increasingly being replicated within the American judicial system, where billionaires like Hank Greenberg can buy themselves endless appeals to justice in the form of David Boies in ways that the rest of us would never dream of doing. (In fact, as if Greenberg’s own wealth weren’t enough to pay for Boies’s services, he’s getting further assistance from fellow financial and corporate titans, such as former Home Depot CEO Ken Langone, who are investing in the case in hopes of profiting from winnings in the verdict.)

Boies’s representation of Greenberg is the legal equivalent of a billionaire’s Super PAC promoting a favored candidate—a show of high-dollar influence that threatens to make a mockery of our claims to democracy and equal justice under the law. “I find [Greenberg’s] allegation completely ludicrous, but it adds dignity” to have Boies arguing the case, says Duke’s Cox. “He’s lent a huge credibility to the process. That’s just the nature of things. He’s playing the game—that’s just the way it is. Judges cut Boies an awful lot of slack, and that’s enabled the suit to have more legs than it otherwise would have.”

*Correction, October 3: The original version of this article gave an incorrect tally for the number of witnesses on the list for the trial. It also used imprecise terminology in referring to the exact nature of AIG's line of business during the housing boom. The company was issuing credit default swaps, not insuring them.

Additional reporting for this piece was provided by Claire Groden.