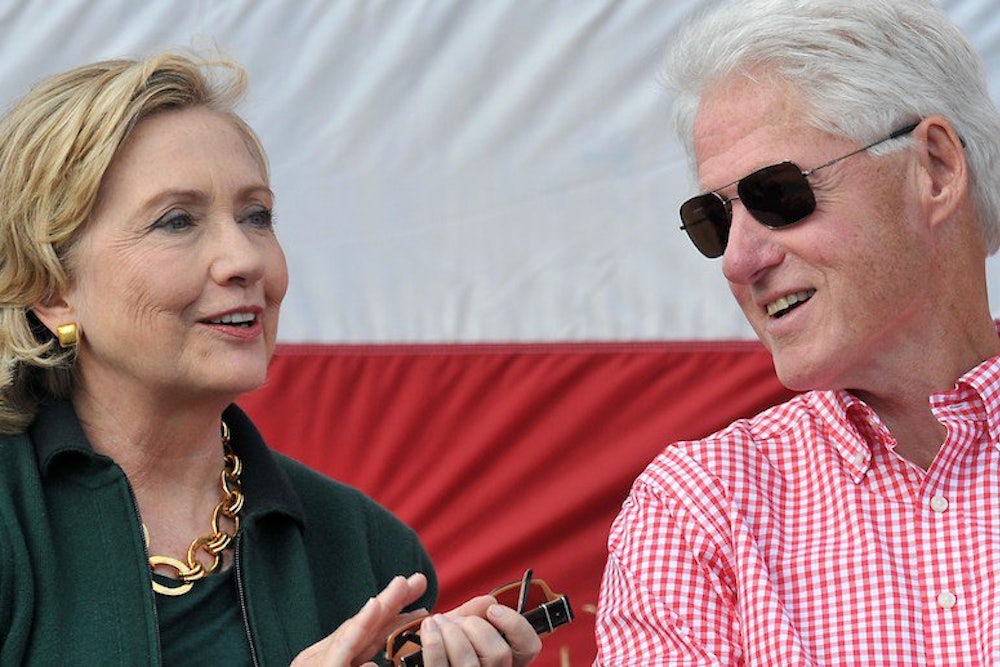

Granted, Hillary Clinton’s appearance at Iowa Senator Tom Harkin’s steak fry on Sunday was of minimal long-term consequence. It was at best a symbolic re-entry to presidential politics, a homage to the rituals of campaigning in Iowa.

Still, between all the rhapsodizing about Harkin (who is retiring next year) and the shout-outs to local candidates, it was possible to discern the contours of a campaign strategy. It’s an approach best summarized as “playing to your strengths.”

Specifically, I counted four pillars of a possible Clinton campaign. First, there was Clinton economic nostalgia—“when it comes to moving America forward, we know what it takes,” Hillary said. Then there were the explicit appeals to female voters, as in “women hold a majority of minimum-wage jobs in this country.” There was an assault on the infernal backwardness of Republicans, whom Clinton referred to as “the guardians of gridlock.” And there was an allusion to the ambitions she nobly repressed by becoming secretary of State. “Senator Obama became President Obama and to my great surprise he asked me to join his team,” Clinton recalled.

All of these themes poll exceptionally well among Democrats. (Particularly the last one—Clinton’s favorability rating within the party surged after she joined Obama’s cabinet.) All of them are sufficiently non-controversial as to position Clinton well against Jeb Bush, Scott Walker, or Marco Rubio. And Clinton showed she could riff on them with an ease and charm that was notably absent from her recent book tour. “It is true, I am thinking about it,” she said, alluding to 2016. “But for today, that is not why I’m here. I’m here for the steak.”

Having said that, I can’t help thinking that playing to her obvious strengths, rather than defusing some of her equally obvious weaknesses, isn’t the optimal strategy for Clinton.

Let me be clear: Hillary Clinton is almost certain to win the Democratic nomination should she decide to contest it. The real question is whether she wins the easy way or the hard way. Does her candidacy alienate activists and dampen Democratic enthusiasm, culminating in a humiliating stumble at some point in the primary process? Or does it rally the party around her and generate momentum heading into the general election?

The concern-troll in me has a hard time seeing how she accomplishes the latter on her current trajectory. It doesn’t take a Clinton-level of political savvy to grasp that the Democratic Party is in an anti-establishment mood. Andrew Cuomo’s remarkably thin margin of victory in the New York gubernatorial primary, and last year’s election of mayor Bill de Blasio, are only the highest-profile examples. Outside New York, populist candidates have been quietly notching victories against well-funded moderates for months with backing from grassroots groups like the Progressive Change Campaign Committee.

But Clinton’s campaign posture seems designed to provoke rather than defuse this populist energy. The Times’ steak-fry table-setter noted that “she has talked to friends and donors in business about how to tackle income inequality without alienating businesses or castigating the wealthy.” Is there a more reliable way to rile up liberals than to conspicuously tiptoe around the powers that be? On foreign policy, it’s one thing to back air strikes in Iraq and Syria, something the American public overwhelmingly supports, and which Clinton’s allies suggest she would have been quick to resort to. But it’s another thing to broadly criticize the incumbent Democratic president as insufficiently interventionist, which suggests a level of hostility to the party’s base.

Yet to imply that Hillary’s potential problems are a function of any particular issue is to miss the point. The problem is the general caution that defines her political style. Of Bill Clinton it was often said that if you put him in a crowded room, he would gravitate toward his harshest critic, determined to win them over. Hillary strikes you as the opposite—the sort who huddles with friends and allies while eying the detractor warily from a distance. The Harkin steak fry speech, and the political strategy it foreshadowed, was basically the rhetorical equivalent of this tic. Hillary’s impulse was to hold close the ideas that have served her well, year in and year out, while steering clear of any possible dissent from establishment opinion. Sensibility-wise, it’s about as far as you can get from where Democrats are these days.

The good news is that Hillary has any number of options for overcoming her chronic risk aversion. My personal preference is that she get behind a financial transactions tax, to rein in profits on Wall Street and tamp down income inequality. But it almost doesn’t matter what the specific policy is so long as it’s sufficiently unorthodox. Michael Tomasky has argued that she could get similar political mileage out of an ambitious family-leave proposal. Not exactly the first thing that came to mind for me—but, hey, whatever works.

In fairness, this year’s Harkin steak fry wasn’t the time or place to announce such a policy, even if she were tempted to go there. What the steak fry speech did make pretty clear that Hillary isn’t exactly in the business of innovating these days. As one solution to the precariousness of middle class life she touted making “college and technical training affordable”—that golden Clinton oldie. She made multiple allusions to her husband’s ‘90s-era incantation that people who “work hard and play by the rules” should have something to show for it. It was rhetorical comfort food—the turns of phrase you go back to when the world is scary and hard to make sense of. Which is all fine and good for the rest of us. But as a window onto the thinking of a future nominee, it was hard not to be disappointed.