The spiritual father of today’s conservative Republican Party, in the assessment of Heather Cox Richardson’s new history To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party, was really a Democrat: James Henry Hammond, a wealthy plantation owner, governor of South Carolina, and a U.S. Senator in the years before the Civil War. Like modern-day conservatives, Hammond was a Constitutional originalist, a believer in states’ rights and small government, a free trader, and an opponent of immigration.

More than that, Hammond was a spokesman for what we would now call the top one percent: the wealthiest members of society who were its natural leaders. In all societies, Hammond proclaimed, there must be an elite class, which in 1850s America was made up of its wealthiest men: the South’s largest slaveholders. Correspondingly, there also must be “a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life. That is, a class requiring but a low order of intellect and but little skill.”

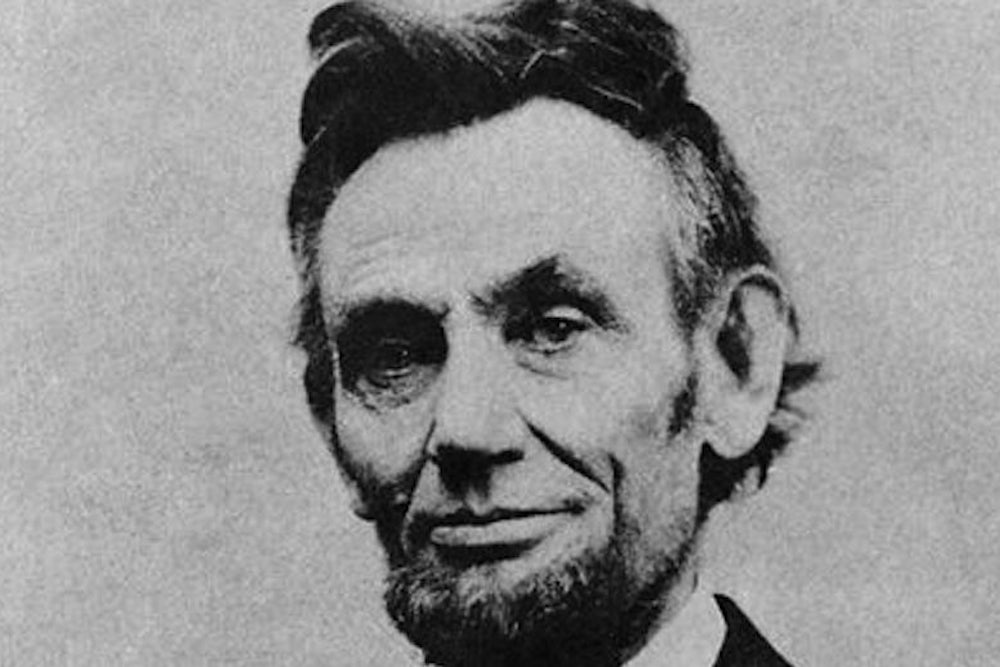

The Republicans, according to Richardson’s history of the party, came together in the 1850s to oppose Hammond’s oligarchic vision. Abraham Lincoln, the most prominent exponent of the new party’s principles, scorned Hammond’s notion that the wealthy should control America’s government and society. Workers were not drudges but the very foundation of the country’s prosperity, since labor did more than capital to create wealth. The Republican Party therefore called for a strong national government to promote the sort of economic development that would allow individual Americans to advance themselves.

Lincoln’s election as president in 1860, and the need to fight and fund the ensuing Civil War, allowed the Republican Party to “reconceive the nation according to their principles,” as Richardson puts it—manifest in the Emancipation Proclamation, pioneering innovations that introduced a national currency and banking system, the Homestead Act granting western lands to individual settlers, the creation of public universities, and the introduction (for the first time in American history) of an income tax.

But the Republican Party, in Richardson’s telling, was born with a sort of Jekyll-Hyde complex. Initially it was a force for progressivism and equal opportunity, but after Lincoln’s assassination it came under the thrall of the new class of wealthy industrialists the Civil War had created. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, reintroduced Hammond’s notion that government activism would lead to wealth redistribution toward the undeserving—and particularly African-Americans—while the Paris Commune sparked fears of a revolution-minded working class. By the 1880s, the Republican Party had ended Southern Reconstruction, jettisoned the idea of government helping to build a middle class, and become corrupted by Gilded Age money in the same way that antebellum Democrats had become the tool of the Slave Power. In short, “Republicans had come to embrace the very ideas their fathers had organized the party to oppose.”

Richardson is not the first to note that the Republican Party has oscillated between moderate and conservative phases. Still, her theory of the party’s historical cycle is intriguing, and her hypothesis that the Confederacy was in a sense reborn in the GOP’s conservative incarnations is both audacious and disturbing. Her repeated invocation of Hammond is somewhat unfair in that no Republican thinkers, to my knowledge, ever looked to him as a model or inspiration, not least because he was a well-known sexual predator as well as a Democrat and slave-owner. But Richardson cleverly highlights Hammond’s claim that the white working classes of the North represented a greater threat to men of property than Southern slaves, showing how fear of workers and minorities has been a constant conservative theme. As the saying goes, history doesn’t repeat itself but it rhymes, and Richardson’s evocation of conservative recurrence has at least some surface plausibility.

In Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel, the potion that Dr. Jekyll imbibed to transform himself into the bestial Hyde eventually wore off, and he returned to his civilized self. So, too, with the Republican Party. In the early twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive movement rebelled against elite domination and restored the Lincoln creed of active government, equal opportunity, and regulation of business. TR’s era of industrial reform passed quickly, however, and the GOP reverted to its business-worshipping, immigrant-hating, worker-fearing ways, resulting in an inevitable economic crash and the nation turning to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to set things right.

The Dr. Jekyll tradition of Republicanism revived under Dwight Eisenhower, who built upon New Deal reforms, raised taxes on the rich, promoted education, and advanced equal opportunity through government investments such as highway construction, which Richardson correctly notes was “the largest public works program in American history.” Ike also worked to extend the Republican principle of equal opportunity to the rest of the world in order to forestall religious and political extremism.

Following the rise of Barry Goldwater and the revitalized conservative movement in the 1960s, however, the GOP has become all Hyde, all the time. Republicans, according to Richardson, once again uphold the racist and elitist limited-government principles of James Henry Hammond. Conservatives have allowed big business to smother democracy and restore inequality in America to levels last seen in the slaveholding South. The Republican Party of 2014 is, in essence, the Southern Democratic Party of the 1850s.

Richardson’s thesis has the virtue of imposing a clear storyline on the Republican Party’s 160-year-long history. But her book is only a reliable guide to the party’s ideological development from the Civil War to Theodore Roosevelt, which is her area of academic expertise. Her take on the GOP’s post-Eisenhower history is thinly sourced and unconvincing.

Even in the book’s early chapters, Richardson’s desire to impose a coherent narrative on the Republican Party’s history means that her focus is on Lincoln’s political ideas—which she examines with clarity and insight—rather than on the messier politics of the era. There’s little analysis here of the difficulties Lincoln encountered in trying to maintain a fractious party made up of members who previously had been Freesoilers, Barnburners, Old Whigs, and Know-Nothings, just as in later chapters there is no mention of political movements such as conservationism and prohibitionism, events such as the Bonus March and the Yalta agreements, or political actors such as Gifford Pinchot and Arthur Vandenberg.

Such omissions become more problematic when Richardson accounts for the rise of modern conservatism. She makes no attempt to grapple with the conservative intellectual revival sparked by William F. Buckley Jr. in the 1950s, or his attempts to find common ground for libertarians, traditionalists, and anti-Communists. “Buckley’s rants would have been dismissed as fringe lunacy,” she insists, “had it not been for one critical factor: race.” While Buckley’s conservatism played on racial concerns, there was much more to it than that. Richardson credits the John Birch Society for spreading Buckley’s ideas to ordinary voters, which both overestimates the Society’s political impact and ignores that Buckley expelled the organization from the conservative movement in the early 1960s. Richardson attributes Goldwater’s gaining the GOP presidential nomination in 1964 to his support from the Birch Society and extremists like Phyllis Schlafly, omitting any consideration of the sophisticated delegate-hunting operation masterminded by F. Clifton White.

Richardson is equally dismissive of the populist character of the Reagan Revolution, seeing it as merely “a screen for the business interests behind Movement Conservatism.” And she describes neoconservatives as a group “organized in 1997,” rather than as an intellectual movement that began in the 1960s as a reconsideration of the limits of liberalism amid the dislocations of that decade and the overreach of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs.

In the end, it’s not clear that Richardson thinks that Republicans should even exist, since she emphasizes that the Lincoln-TR-Eisenhower tradition of Republicanism has migrated to the Democratic Party. Indeed, Richardson anoints Barack Obama as “the embodiment of the dream Lincoln had articulated, Theodore Roosevelt had adapted to the era of industrialization, and Eisenhower had formulated for the modern world.” But if the best Republican beliefs are identical with Democratic liberalism, and conservatism is too pernicious to function even as a check on liberalism, then why have a Republican Party at all?

There is no recognition in To Make Men Free that Lincoln’s ideas of individual merit and equal opportunity are at odds with liberal doctrines of group rights and equal outcomes, or that Democrats wholeheartedly reject both TR’s economic nationalism and Eisenhower’s pro-business fiscal conservatism. If Richardson had chosen to conceive of the Republican Party’s history in more political terms, the GOP would have appeared less as a Jekyll/Hyde character, and still less as a reincarnation of antebellum slave-ocracy. Rather, it would be seen as a party that, through most of its history, has presented itself as a vehicle for achieving the same ends of peace and prosperity favored by Democrats, but through significantly different means.

Richardson’s account is likely to find favor with liberals, since she portrays the modern Republican Party as the repository of America’s most vile traditions while the Democratic Party is heir to all the best. But partisan political allegory is no substitute for history, and no help in discerning how the Republicans might recover their identity as the Party of Lincoln.