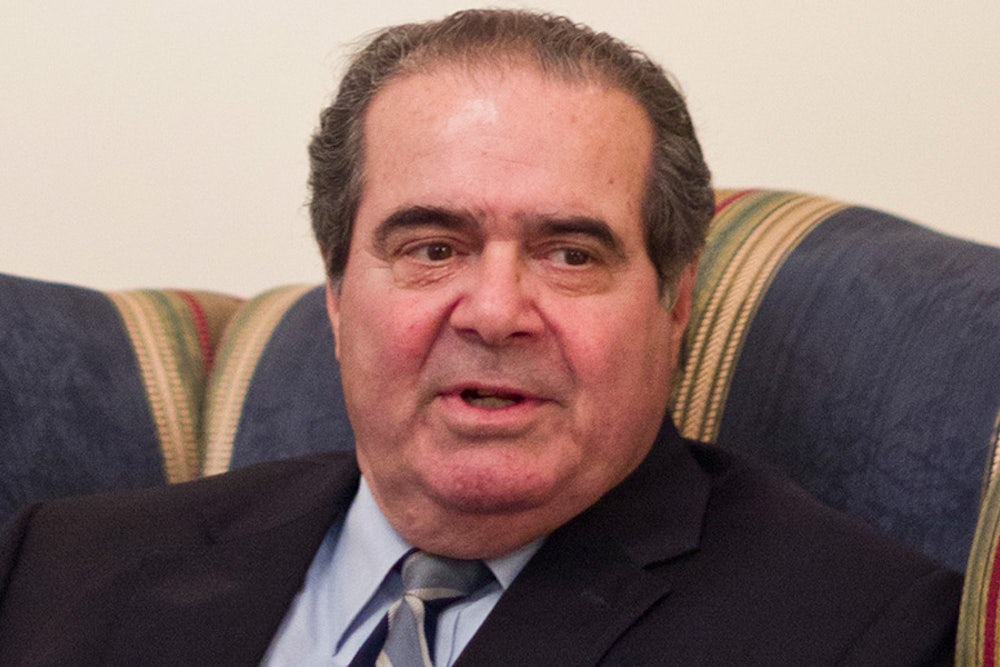

Scalia: A Court of One by Bruce Allen Murphy (Simon & Schuster).

On October 15, 1987, as Justice Antonin Scalia settled into his second term at the Supreme Court, he emerged from conference with his eight colleagues to discover a peculiar scene unfolding within the building’s typically staid corridors. Just outside of the conference room began a seemingly endless trail of white placards decorating the hallway carpet. On each placard, in handwritten lettering, appeared the name of a single prominent opinion that Justice William Brennan had written for the Court during his lengthy, high-profile tenure. Brennan’s law clerks had assembled the parading placards to honor the liberal hero’s thirtieth anniversary on the Court. As Brennan approached each sign, a law clerk later recalled, he would gleefully exclaim yet another landmark opinion’s name and then pause for a moment to recall his handiwork. Brennan was unaware that the Court’s newest member was following him only a few steps behind, grimly inspecting the assemblage of cases along the way. If Brennan was enjoying a stroll down Memory Lane, Scalia was enduring a slog up Trauma Avenue. For Scalia, Brennan’s extended run of liberal victories came at the cost of distorting the judiciary’s proper role in a democracy. When the trail of placards finally ended at Brennan’s chambers, Scalia managed to find a good-natured way of expressing his deep disagreement: “My Lord, Bill, have you got a lot to answer for!”

Today, some twenty-eight years into Scalia’s justiceship, legal liberals increasingly understand that he has a considerable amount to answer for in his own right. But Scalia’s legacy, unlike Brennan’s, would not be especially apparent from aggregating the landmark opinions that he has written on the Court’s behalf. This discrepancy does not mean that Scalia’s résumé is altogether lacking in this regard. During the last decade alone, Scalia has issued major opinions redefining the Second Amendment’s protection for firearms possession in District of Columbia v. Heller and the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause in Crawford v. Washington. Even accounting for Scalia’s many memorable opinions written in dissent would inadequately trace his legal imprint.

Instead of his influence being confined to a discrete set of writings or narrow doctrinal categories, Scalia has shaped modern American law in ways more overarching and even elemental. Elena Kagan, when she was dean of Harvard Law School, expressed this point vividly while presiding over Scalia’s return to his alma mater in 2007. “His views on textualism and originalism, his views on the role of judges in our society, on the practice of judging, have really transformed the terms of legal debate in this country,” Kagan said. “[Scalia] is the justice who has had the most important impact over the years on how we think and talk about the law.” This statement can be understood to identify Scalia’s influence as occurring within at least three distinct arenas, each requiring some elaboration.

First, when Kagan invoked “textualism,” she referred to the Court’s increased emphasis on legislative text when confronting a question of statutory interpretation. Put slightly differently, Scalia has waged an incredibly successful war against judges relying upon legislative history to determine a statute’s meaning. When judges resort to materials such as committee reports or legislators’ floor statements about a bill, Scalia claims, they almost invariably cherry-pick statements supporting their preferred outcomes. Scalia, amplifying a critique initially pressed by Judge Harold Leventhal, has condemned using legislative history as the “equivalent of looking over the faces of the crowd at a large cocktail party and picking out your friends.” Judicial usage of legislative history has not exactly gone extinct, but relative to its heyday in our not-so-distant legal past, it has rapidly become an endangered species. No legal figure has played a more critical role in the decline of legislative history than Scalia; it is this development that represents his most pervasive influence on how judges write opinions every day throughout the nation.

Second, when Kagan mentioned “originalism,” she highlighted Scalia’s preferred mode for interpreting the Constitution by appealing to history. The concept of originalism certainly existed long before Scalia became its most familiar practitioner. But Scalia played a pivotal intellectual role in refining the concept. Shortly before his Supreme Court nomination, Scalia delivered a major address calling on originalists to relocate their fundamental inquiry. Rather than searching for the “original intent” of constitutional Framers, Scalia insisted, originalists should search for the Constitution’s “original meaning” for the public. This shift toward “original meaning” represented a shrewd intervention, suggesting that the Framers’ own understandings of constitutional text were less important than what ordinary citizens would have understood that text to mean. Perhaps as importantly, Scalia has advocated originalism tirelessly, availing himself of innumerable public- speaking opportunities to disseminate his constitutional theory.

Scalia’s efforts have succeeded in transforming what had been a fringe phenomenon into a central part of the nation’s mainstream constitutional conversation. At the Court, the most striking instance of this phenomenon at work is Justice John Paul Stevens’s lead dissent in Heller, where he aimed to counter Scalia’s majority opinion by also utilizing originalist methods. Stevens’s remarkable concession that originalism should define the Second Amendment’s contours provides a stark testament to the theory’s clout. It would be inaccurate to maintain that originalism is the Court’s dominant mode of constitutional interpretation today, but it is no longer a laughingstock. Elevating a constitutional theory’s status from risibility to respectability is no modest attainment. Within academia, moreover, originalism’s ascent has been even more dramatic. Self-avowed originalists can now be found on several leading law school faculties. More tellingly still, not all of these self-avowed originalists are conservatives, as some liberal law professors claim that originalism, properly understood, supports progressive outcomes. Nowadays even liberal legal scholars who reject originalism sometimes feel compelled to vanquish the theory before they turn to the business of propounding their own constitutional notions.

Finally, when Kagan addressed Scalia’s influence on legal debate and discussion, her statement applied not only in the broad sense of how lawyers communicate, but also in the narrower sense of how oral argument is conducted at the Supreme Court. Before Scalia’s arrival, arguments were markedly more genteel affairs, with justices generally lobbing a modest number of questions to counsel and taking care to avoid extended colloquies. (Legend has it that oral advocates during this era occasionally managed to complete two or even three full sentences before they were visited by the next question.) Scalia eschewed this tradition of gentility, challenging lawyers beginning in his very first oral argument with an unusually high volume of unusually targeted questioning. The onslaught left at least one of Scalia’s new colleagues taken aback, as Justice Lewis Powell muttered, “Do you think he knows that the rest of us are here?”

When one attends oral argument these days, Scalia’s style of questioning does not seem aberrant because the other justices have largely embraced his aggressive and forthright method of questioning. It is tempting to suppose that the current brisk pace of arguments was an inevitable development, but that would be a mistake. After all, earlier justices also had the incentive to hurl lots of challenging questions in an effort to mold perceptions of cases. No one actually seized the opportunity until Scalia.

Given the size of his imprint on modern American law, Scalia’s ideas merit sustained examination by lawyers and non-lawyers alike. Even those who conclude that his ideas should largely be rejected have an obligation to understand them in their strongest forms. At times Bruce Allen Murphy’s biography performs an admirable job of elucidating his subject’s thinking. The book accomplishes this task most effectively by simply providing many generous excerpts from Scalia’s speeches and opinions, enabling the justice to make his various arguments for himself. Murphy’s biography also displays formidable research skills, as he seems to have uncovered every word that Scalia has uttered in public during the last several decades. But whatever the book’s virtues, they are dwarfed by its vituperative attacks on Scalia’s character and even on his religion.

Biographers are under no obligation to portray their protagonists in relentlessly favorable terms. To the contrary, exemplary biographers offer critical assessments of their subjects, lest they lapse into hagiography. But biographers should also make substantial efforts to understand their subjects as the subjects might understand themselves. In addition, they should acknowledge that some pivotal moments in the lives of many subjects admit of different interpretations, ranging from the cynical to the benign. Murphy’s book, alas, does not trouble itself much with such tasks, as it consistently casts Scalia’s actions and motivations in the least flattering light available. Indeed, Murphy’s portrait of Scalia consists overwhelmingly of warts—and, worse still, some of the blemishes he depicts seem more contrived than real.

One revealing example of Murphy’s penchant for focusing too heavily on Scalia’s supposed character-based shortcomings arises in his treatment of then–Judge Scalia’s speech in 1986 extolling “original meaning.” Murphy views the speech not primarily as Scalia’s contribution to a growing movement, but as his underhanded effort to snatch a Supreme Court nomination before fellow Judge Robert Bork, an advocate of “original intent,” received the appointment. “This was Scalia at his most ambitious, reaching for the top rung on the federal judicial ladder through a campaign-style speech,” Murphy writes. “The fact that it also undercut a competitor for the Court appointment could almost be lost in the friendly, entertaining tone of the speech.” Elsewhere Murphy derides Scalia’s effort at “explaining why his brand of judicial conservatism was better than that of Judge Bork.”

By invoking the marketing executive’s mentality, and gesturing toward the notion of brand differentiation, Murphy makes it seem as if Scalia’s intellectual insight was tantamount to declaring Pepsi The Choice of a New Generation. In assessing whether Scalia may have delivered the speech because at least in part he actually believed its content, it may be worth noting that virtually all sophisticated originalists now conceive of themselves as attempting to discern “original meaning” and virtually none, conversely, embrace “original intent.” The reason that the term “original meaning” is ascendant in scholarly circles is not because Scalia somehow managed to bully professors into accepting it, but because they believe that his term best describes the originalist enterprise.

Murphy also misleadingly alleges that Scalia’s public addresses initiated numerous undesirable developments at the institution that he joined. These speeches, Murphy claims, “began the process of politicizing the Court and launching the partisan warfare among the justices.” But Scalia cannot possibly bear responsibility for starting that process at the Court, because it antedated his arrival. In a well-known speech delivered one year before Scalia’s confirmation, Justice Brennan made the case for living constitutionalism, and in the process he dismissed originalism as “little more than arrogance cloaked as humility.” The press understood Brennan to be locking horns with Attorney General Edwin Meese III, who had recently issued a prominent call for originalism. But as Brennan’s biographers Seth Stern and Stephen Wermiel have written, Brennan had given slightly altered versions of the address on several prior occasions, even before Meese entered the fray. Brennan’s time on the speaker circuit renders it dubious for Murphy to protest that Scalia “single-handedly ... changed the code of conduct for extrajudicial behavior by justices on the Supreme Court,” and that his talks “changed the conventional perception of the justices from lofty judicial figures to partisan political actors.” Scalia undeniably bears some responsibility for accelerating these trends. Yet he cannot accurately be deemed the sole animating cause.

Even when Scalia’s conduct invites legitimate skepticism, moreover, Murphy overplays his hand. The book, quite appropriately, dedicates significant space to exploring Scalia’s role in Bush v. Gore. Had the parties’ positions been inverted, it is all too easy to envision Justice Scalia excoriating that opinion’s novel reading of the Equal Protection Clause. But Murphy stretches further to contend that Scalia’s real motivation in the case was not merely to install fellow Republican George W. Bush as president, but also to install himself as chief justice. In 2000, nearly five full years before Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, Murphy suggests that Scalia somehow sensed Rehnquist’s health was deteriorating and set about doing virtually anything possible to position himself for the top job. The fundamental facts of Bush v. Gore are plenty discrediting; there is no need for larding such additional sorts of dismal motivations.

On no topic, however, is Murphy’s treatment more objectionable than his fixation on Scalia’s Catholicism. Early in his book Murphy asserts that, alongside enjoying a good argument, Scalia’s central trait—one “that defined him at every stage in his life”—is “his unwaver ing adherence to the traditional Roman Catholic faith he had learned from his Italian American parents during his childhood.” Murphy then proceeds to advance this argument with fanatical, one might even say religious, fervor. Indeed, relying only on this biography, readers might be forgiven for concluding that Scalia is primarily a religious figure who manages to squeeze in a little legal studying on the side.

Murphy’s religious preoccupations are most apparent in his salacious treatment of Scalia’s relationship with Opus Dei, a small institution dedicated to observing a devout form of Catholicism. In the popular imagination, that institution is best known for its depiction in The Da Vinci Code as a bizarre group of conspirators. Murphy blithely repeats rumors asserting Scalia belongs to Opus Dei, whose membership ranks are not public, and then portrays the organization in extremely negative terms. Murphy quotes a writer he identifies as a “critic” of Opus Dei contending that among the organization’s “main tenets are that God is an authoritarian and, therefore, Opus Dei adherents support dictatorial societies ... and that God created a natural order of life in which the rich are rich and the poor are poor—and the divine order of inequality shouldn’t be disrupted.” After echoing these criticisms, Murphy does not do readers the service of informing them whether the critic’s claims are accurate.

But repeating these unexplored criticisms seems downright mild in comparison to those Murphy places in a breathtaking endnote: “Some believe that the most dedicated of [Opus Dei’s] members practice self-sacrifice by sleeping on a board or the floor once a week, and commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus through ‘self-mortification,’ beating themselves with a cord whip called a ‘discipline’ and wearing an uncomfortable hair shirt undergarment or even a spiked chain, called a ‘cilice,’ designed to break the skin of their upper thigh for a period of time each day in order to induce constant pain.” This passage seems designed to make readers wonder precisely what Justice Scalia is concealing under his robe.

So the question becomes: how extensive is Justice Scalia’s association with Opus Dei? Evidently, according to Murphy’s own sources, there is no association at all. Not that Murphy himself is quite so unequivocal on the point. He writes that, although Scalia’s detractors have asserted that he belongs to Opus Dei, the strongest source on this subject could not establish such a linkage: “The best authority on this question, John L. Allen, Jr., who relied on his extensive Vatican contacts to uncover the worldwide lists of Opus Dei members, was unable to link Scalia to the organization’s membership.”

But Allen, who has written what Murphy labels “the definitive book” on Opus Dei, went much further on this question than Murphy allows. Allen did not merely indicate that he failed to discover Scalia’s membership in the institution; instead Allen affirmatively indicates he discovered that Scalia did not belong to the institution. “While Opus Dei spokespersons will not comment on the record about whether a given individual is a member, they are often willing to do so off the record, especially when it’s a high-profile person,” Allen wrote. “For example, I had no trouble establishing that, media reports to the contrary, neither former FBI director Louis Freeh nor U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia is a member of Opus Dei.” Allen made that determination nine years ago, and Murphy produces no evidence to suggest anything has changed. Ultimately, Murphy declares that determining whether Scalia is technically a member of Opus Dei is immaterial to his argument: “Whether Scalia was a member of Opus Dei or not is beside the question, for his conservative religious views, his textualism and originalism legal theories, together with his judicial decisions and his public speeches, were all perfectly in harmony with it.” This tactic’s impudence is enough to make practitioners of guilt by association blush with embarrassment.

Incredibly, Murphy proceeds to contend not merely that Scalia’s judicial opinions are compatible with the principles of Opus Dei, but that his preferred interpretative techniques can be viewed as devices for transforming his religious doctrine into legal doctrine. Murphy sets the stage for this claim by drawing parallels between “religious leaders and originalist judges,” both of whom offer interpretations by “adopting a similar authoritarian relationship to the parishioners and lawyers before them, wrapped in their own sense of certainty.” And, then, in a truly astonishing passage, Murphy writes: “In sum, pre–Vatican II Catholicism and legal originalism / textualism are so parallel in their analytical approach that by using his originalism theory Scalia could accomplish as a judge all that his religion commanded without ever having to acknowledge using his faith in doing so.” Suggesting that Justice Scalia is using his seat on the Supreme Court to promote Catholic teachings is an unusually aggressive move. Regrettably for Murphy, the claim does not withstand much scrutiny even in the highly inflammatory context in which he lodges it.

In a chapter called “Opus Scotus,” Murphy suggests that Scalia answers to Catholicism’s command in his discussion of Gonzales v. Carhart, where in 2007 Scalia joined a bare five-justice majority in upholding the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act. Carhart dramatically undermined a Court precedent that had recently invalidated a similar statute. That all five justices in the majority were Catholic, and that the four dissenting justices were either Jewish or Protestant, may make it seem inescapable that Scalia’s vote in Carhart simply implemented the Vatican’s dictate.

But such a reading appears misguided. In order to understand why this is so, it is necessary to juxtapose Justice Scalia’s constitutional view on abortion with the view of a hypothetical justice dedicated to ensuring that constitutional law reflected Catholic doctrine as closely as possible. Although Scalia has consistently called for Roe v. Wade to be overturned, he does not contend that the Constitution prohibits legislators from enacting measures protecting women’s reproductive autonomy. Instead Scalia maintains that the Constitution says nothing about abortion whatsoever. “The States may, if they wish, permit abortion on demand, but the Constitution does not require them to do so,” Scalia wrote in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey in 1992. “The permissibility of abortion, and the limitations upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.” In another opinion, Scalia wrote that the Court had no business “volunteering a judicial answer to the nonjusticiable question of when human life begins.”

If Scalia were truly committed to eliminating the gap between Catholicism and constitutionalism, many observers would surely find that these positions fail spectacularly at accomplishing the task. It requires no great familiarity with Catholicism to know that the Church understands life to begin at conception. A jurist committed to operationalizing that notion would encounter little difficulty finding, contra Scalia, that the Constitution clearly forbids laws permitting women to receive abortions under any circumstances. Such an interpretation would begin by noting the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, which expressly protect against governmental deprivations of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Accordingly, from these constitutional hooks, one can quite plausibly envision a Supreme Court justice, consistent with Catholic doctrine, determining that when a state permits any woman to have an abortion, it violates Due Process principles because it allows unborn life to be extinguished. On this view, Scalia’s aversion to this sort of far-reaching interpretation and his willingness to let the abortion issue be decided in the political realm can be construed as abdicating his constitutional responsibilities.

These deficiencies in Murphy’s approach may seem glaringly obvious, but his book has received a surprisingly warm reception in some estimable quarters. At least one reviewer has even showered praise on Murphy for his brave, penetrating insights into Scalia’s religion. Writing in The Atlantic, Dahlia Lithwick commended Murphy as “a timely and unintimidated biographer” who “refuses to be daunted by the silence that surrounds most discussions about religion and the Court.” In Lithwick’s view, “Murphy’s conclusion—at once obvious and subversive—is that Justice Scalia is very much a product of his deeply held Catholic faith.” Failure to acknowledge the ample flaws in Murphy’s treatment of religion is a dereliction. But celebrating the biography for its bold willingness to speak truth to power is perverse.

The point here is not to suggest that the issue of religion should never be broached when it comes to assessing justices. That position is indefensible. Justices bring a wide variety of backgrounds and experiences when they ascend to the Court, and it would be foolish to maintain that at least some of those experiences do not at least sometimes inform their legal views. In the particular case of Scalia, moreover, it would be irresponsible for any biographer to avoid discussing his religion at some length. Scalia, from an early age, has often spoken publicly and passionately about the important role that religion plays in his life. He has written significant opinions that directly address the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause. Pondering the potential linkages between Scalia’s Catholicism and his jurisprudence, in those two constitutional areas and beyond, is perfectly fair game. Still, it goes too far to imply that a justice’s religion, standing alone, commanded that he or she vote in a particular way in a particular case, let alone in a whole series of cases. The reason such attributions of judicial motivation are ill-advised is that they cannot be verified. Isolating a single aspect of a justice’s identity as the driving force for an opinion is almost always futile, since judges, like most human beings, have complex identities.

Consider, for example, the multiple non-religious identities that may have played some role in motivating Scalia’s vote in Carhart. First, his partisan identity: before joining the bench, Scalia worked in two Republican presidential administrations, and the GOP has not exactly kept its desire to overturn Roe a state secret. Second, his male identity: although sex is easy to overlook as a causal explanation, it hardly seems extravagant to maintain that men may generally be less sensitive than women to the undesirable consequences of upholding abortion regulations. Third, his educational identity: Scalia studied at Harvard Law School during the late 1950s, when Felix Frankfurter’s admonitions about the dangers of invalidating democratically enacted legislation were revered. Might these various identities—as a partisan, as a man, as a proponent of judicial restraint—or some combination thereof have driven Scalia’s vote to uphold the legislation in Carhart?

Identifying a particular religious tradition as requiring a particular judicial behavior is particularly dicey because individuals often draw very different lessons from broadly similar religious upbringings. Catholicism is a sufficiently capacious religion that it often includes robust commitments to social justice and offering aid to society’s marginalized citizens. Perhaps Justice Brennan’s vote to invalidate abortion laws in Roe v. Wade, and scores of other liberal votes besides, should be attributed to those aspects of his Catholicism? If religion can plausibly be invoked to explain Catholic justices voting both ways on abortion regulations, it may not actually do a very helpful job of explaining either vote. It also seems worth noting that it was Justice Anthony Kennedy, a Catholic, who cast the crucial vote in Casey, refusing to wholly abandon Roe. While Justice Sonia Sotomayor, also a Catholic, has not voted in a case at the Court directly challenging Roe, it would be utterly shocking if she did not vote with her fellow Democratic-appointed colleagues whenever that opportunity should arise. Although Murphy aims to resolve such divisions among the Court’s Catholics by invoking their varied attitudes toward religious traditionalism, the messy realities resist his tidy narrative.

Scalia’s admirers may—somewhat counterintuitively—hope that Murphy’s book enjoys wide circulation, because it must be deemed unsuccessful even on its own terms. There can be no question that Murphy intends readers to walk away from his book with a thoroughly negative impression of Scalia, but his hatchet is so crude and so wanton that it falls well short of achieving its intended effect. Even readers who are unsympathetic to Scalia’s legal vision may find themselves regularly leaping to his defense, supplying the counterarguments, explanations, and qualifications that Murphy too often disregards.

Legal liberals should find Murphy’s grotesque rendering of Scalia especially distressing because the stakes could hardly be higher. Scalia’s theories have already made deep inroads into conventional legal understandings. Today’s generation of young lawyers will determine whether those theories become more central still. When Scalia’s intellectual adversaries attack a virtually unrecognizable caricature, they leave the unfortunate impression that they are incapable of winning the argument on the merits. If legal liberals are going to prevail in the long run, they must comprehend that the many profound problems with Scalia’s views are not characterological or ecclesiastical; they are jurisprudential.