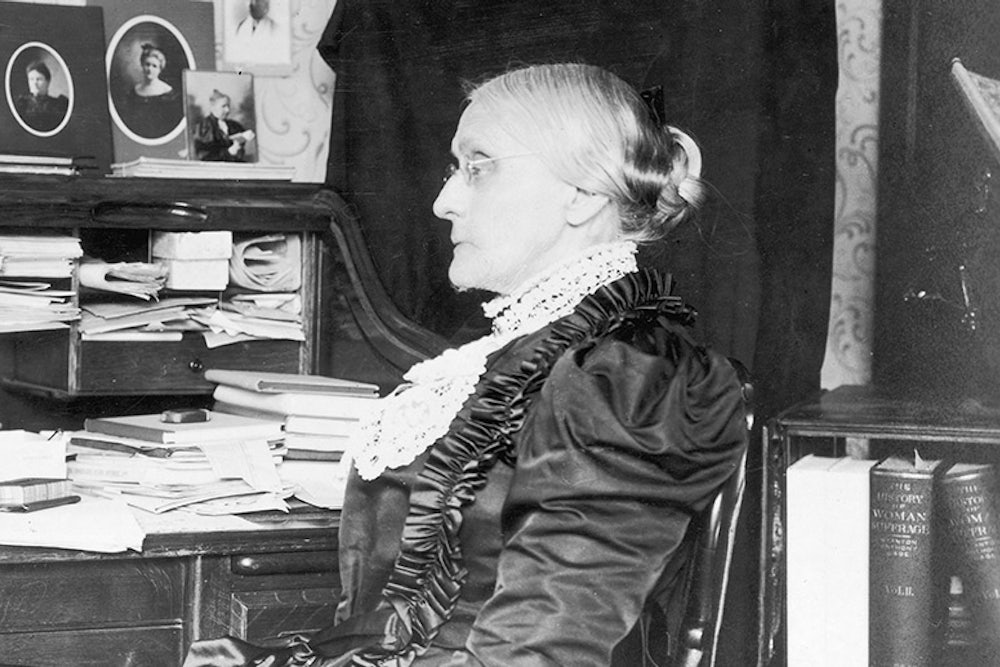

This week, the education journalist Dana Goldstein published The Teacher Wars: A History of America’s Most Embattled Profession (Doubleday). Goldstein's book is full of stories of women who transformed school houses and the nation. Catherine Beecher, the sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, was one of education's earliest and most influential reformers; her belief in women's suitability as educators and scholars helped turn teaching into a female profession. Other reformers and social agitators, including the suffragist and abolitionist Susan B. Anthony, early female attorney and presidential contender Belva Lockwood, and the abolitionist Charlotte Forten Grimké, also worked as teachers for some parts of their lives. The book has already received lots of attention for reminding us that the contemporary controversies over education policy are not new. But the other thing Goldstein shows us is how intertwined the stories of teachers, reformers, and women's and civil rights activists have been.

I’ll start simple: How is the development of the teaching profession intertwined with the expansion of professional opportunity for women, starting from the moment that 19th-century education reformer Catherine Beecher conceived of teaching as a suitable profession for middle-class white women?

The two are absolutely linked. [Almost as soon as teaching was feminized] new opportunities opened up for women, which in turn had an impact on the teaching profession. A great example of this is Belva Lockwood, who starts teaching at the age of 14 in an upstate New York one-room schoolhouse. She’s hit by the feminist bug [in the mid 19th century] and within a matter of years she’s become an attorney, lobbying to become the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court, and eventually she runs for president ... two times! But a lot of her feminism is driven by her anger that she’s getting paid less than male teachers.

And the same thing triggered Susan B. Anthony to activism—the gender-based pay she experienced as a teacher.

Anthony is motivated to get into teaching by her desire to resist marriage, right?

Yes! One of the things we see developing in Anthony’s personality, from childhood, is disgust for the idea of marriage. At the time, it was the way a woman would achieve economic stability, something you had to do. But even in letters home from boarding school as a girl, when her teenage friend marries a middle-aged widower with six children, she is totally horrified and writes “I should think any female would rather live and die an old maid.” Which she ends up doing herself! Anthony is just incredibly prescient and so self-aware for a 17-year-old girl, especially if you think of the society she’s raised in. A lot of her strength comes from her Quaker faith. She becomes a teacher because it’s a way out of this fate.

I’m just finishing writing a book on unmarried women, and in fact lots of 19th century women, even those from conservative backgrounds, are sophisticated and articulate in their disdain for marriage as an imperative. Maybe because that was the thing for which young women were prepared, so they gave a lot of thought to the ways it might end badly.

Actually, Catherine Beecher has the same fear. She had been engaged to a wonderful man who died tragically, but as a teenager she wrote similar letters, in which she said that she truly feared marriage. She feared childbirth as many women did in the 19th century: There was a real danger of death! Beecher was committed to feminizing the teaching profession both because she believed passionately that teaching was a wonderful way to get women involved in the public sphere, and to improve education, but also because she knew she was not going to get married and was looking for something useful to do with her own life.

What’s ironic then is that Beecher, who saw teaching as an alternative to marriage, sells her idea to the public by suggesting that women could be paid (and would be paid, for a long time!) so much less than men, thus saving taxpayers money. Underpaying women seems at cross-purposes with providing women with an economically viable alternative to marriage, no?

I think for Beecher this was a pragmatic way to get her point across. She was very ambitious and very smart. She needed to make this pragmatic appeal to cheapness because one of the main barriers for early education reformers was trying to make education compulsory, so that parents had to send their kids to school. And resistance to raising taxes was the major barrier to this movement.

But the fights that would eventually erupt over gendered pay inequity were fundamental to the participation of women in the labor movement, right?

Yes, we see in 1897, when the first teachers union is founded, this assumption that we can get away with [paying women less] because most women are married and husbands are supporting them. But actually, a lot of female teachers were not only supporting themselves but also family members—elderly parents, sometimes younger siblings if their mother was widowed or dad was unemployed. So what Margaret Haley and Katherine Goggin, the founders of the teachers union movement, say [at the turn of the 20th century] is: This is totally absurd!

It’s also fascinating that teaching is tied to the expansion of public intellectual life for black women in the Progressive Era. You write particularly about educators Charlotte Forten and Anna Julia Cooper.

In the black community something different is going on, because the teacher was such a beloved and respected figure. W.E.B. Du Bois argued that the “preacher and teacher” represent African-Americans’ quest for a a better life. So there is this inspiring idealism about teaching in a black community, and less [arguing] over compensation and taxation.

But what’s interesting is that for Anna Julia Cooper, who spent her life as an educator, and mostly as a single woman, pay does matter. And at different points in her career, she does agitate politically to argue for higher pay.

Some of the relationships between the figures in your book, and the kinds of reform they push for, recalled the history of the women’s movement itself. There are generational differences between Beecher and Anthony, class differences between the privileged Beecher and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and less privileged Cooper and Anthony. There is Stanton’s belief that women must take responsibility for liberating themselves personally, versus Cooper, who is interested in the more communal project of lifting up the race. So many of these issues still divide activists.

Yes, and at the heart of so much of that is one of most interesting cleavages in feminism: whether or not the feminist in question thought teaching was a respectable job. This divides lifelong compatriots Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: Anthony is very concerned with improving labor conditions, and in making teaching a more respectable job. Stanton, meanwhile, is going all around the country giving speeches urging people, ‘Don’t allow your daughters to become teachers!” Stanton really buys into the argument that Beecher first makes, that being a teacher is like being a mother. Stanton herself is a person who’s had a lot of difficult pregnancies, a difficult marriage in some respects, and she longs to liberate women from these expectations, from this crap work, this drudgery.

Meanwhile, Anna Julia Cooper is resisting this idea, and claiming that teaching is the most exalted work because it’s a way for her to lift up her community. For Anna Julia Cooper, women’s rights are about women as community leaders, while Stanton is much more interested in the woman as being autonomous over her own destiny.

Let’s go back to Belva Lockwood, the teacher who went on to argue in front of the Supreme Court, and run for president in 1884 and 1888, for a minute. She leaves teaching and heads to politics, an example of Stanton-style feminism’s early push away from teaching, which started to happen nearly immediately after Beecher herds women into teaching. You write, in reference to Lockwood, “when ambitious women left the underfunded, often maligned teaching profession to better their lives, public education lost powerful advocates for both teachers and students needs.” This is, of course, reminiscent of the common critique that second-wave feminism, a century after Lockwood, destroyed our national education system because so many brilliant women were suddenly able to go into other fields, and did.

The trend line is just a lot longer than we assume it is. There is this notion that second-wave feminism effectively ruined teaching. But if you compare the qualifications of teachers before and after the second wave, it’s hard to see a marked drop-off in teacher quality.

But I also took a lot of oral histories for this book, and there is no question that the women I interviewed who entered the profession in the 50s and early 60s had a level of ambition that today we might associate with someone who becomes, say, a Supreme Court clerk. It was just astounding. And I think most of them probably wouldn’t have become teachers in other [contemporary] circumstances.

What’s interesting is that 76 percent of teachers are still women today. That’s because teaching remains the most common first step out of the working class and into the middle class. So we’re always having new generations of women who are, say, the first in their families to graduate from college.

One interesting thing I just found out is that Teach for America is 73 percent female, which blew me away! Even though TFA is so much more successful at recruiting teachers of color, which is wonderful, they have the same male-female problem that the rest of the profession has. What that suggests to me is that even having this entire reform conversation about making teaching more rigorous, there is so much baggage; even the path that is perceived to be the most elite is still overwhelmingly female.

I was really interested in Beecher’s original conception of teaching as an alternative to marriage, and as a kind of monastic alternative. The idea that female teachers were supposed to be pure moral influences on children persisted for a long time. How did the sexual revolution of the late 20th century have an impact on that?

Well, for one thing, prior to the sexual revolution, teachers would often lose jobs after getting pregnant, even when they were married. There was this incredibly insane idea that kids didn’t know where babies came from. But ten years later, that practice was just done away with.

Then there’s the issue of sexual panic in schools. Interestingly, Campbell Brown, who’s now so active in the anti-teacher-tenure activism, got her start in education policy as someone who spread panic over teacher sexual assault. There is this prurient fascination with the idea that teachers have sexual interest in children.

When you see that there are eight of 80,000 New York City teachers who have these cases against them [you see how rare it is]. But looking at literature about teachers—including Claire Messud’s last novel, or Tampa by Alissa Nutting—you find female teacher characters who are almost always single, and often monstrously so. Sometimes not in a sexual way, but because the character lacks a private life, she’s going to become unhealthily obsessed in some way with your child.

So are teachers still tasked with moral uplift?

Yes. We’ve always put high expectations on teachers in terms of role they play in civic life but the way we define that role has changed over time. In the early 19th century there is this Christian, moral definition of the female teacher, who’s responsible for saving the soul of the child. During World Wars I and II it’s more of a patriotic mission, and teachers were expected and often required to take oaths supporting America’s war effort. Today the ideology is all about closing achievement gaps, and the moral pressure we put on teachers is to be the fix for socio-economic inequality.

So there’s a sloughing off of larger civic responsibility for addressing inequality onto teachers, as there is onto parents, which seems tied to the fact that we think of parenting as a female responsibility and teaching as a female vocation. It’s low-paid and unpaid women’s jobs to fix everything?

I think idea that parents and teachers are flip sides of same coin is very tied up with fact that teachers are women. And no, we don’t have as big of a push or as loud a debate about raising the minimum wage as we do about attacking inequality through teaching, even though one of those things is a much more direct way to fix the problem of deepening inequality.

One of the points I like to make is that teachers themselves are victims of that deepening inequality! Teachers’ purchasing power, relative to other college-educated workers, has declined since 1940. That’s because teachers’ incomes have not been rising relative to inflation, and also because we’ve seen an explosive [rise in wages] in the business world, in finance. So they’re the victims of inequality, and also responsible for addressing it.