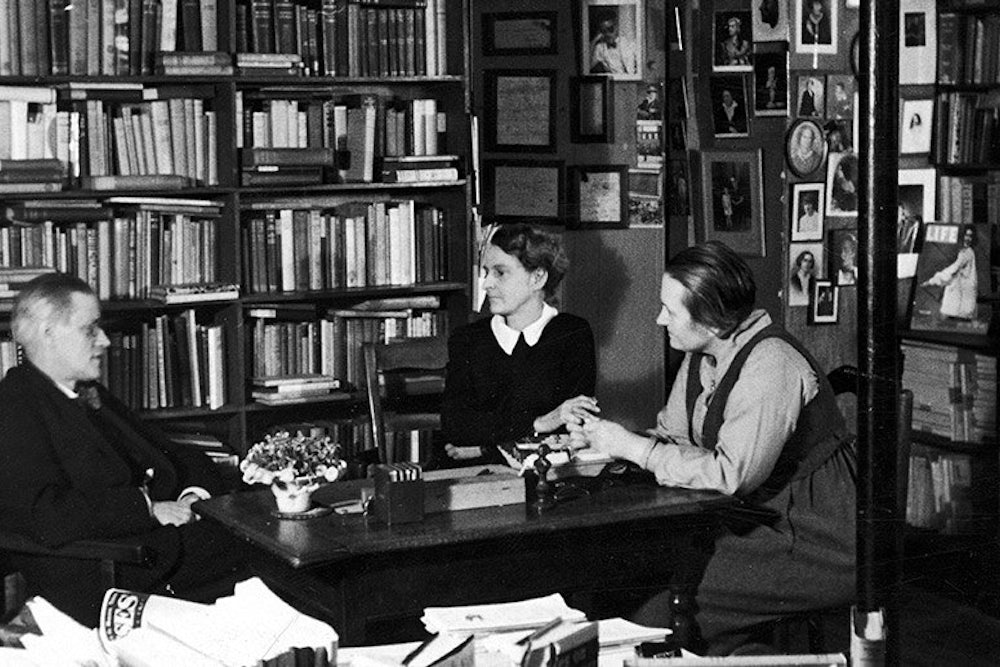

It is tea time at the Joyces’. Mrs. Joyce gives us the best tea and the nicest cakes that are to be had in any house in Paris. The children are here, now a young man and a young woman: George, a singer, Lucia, charming and retiring. Mrs. Joyce, with her rich personality, her sincere and steadfast character, is an ideal companion for a man who has to do Joyce’s work. She talks about Galway to me, and the old rain-soaked town comes before me as she talks about the square, the churches, the convent in which were passed many of her years. Some close friends, Irish, English, French, American, are here for tea. It is Joyce’s birthday—his forty-seventh—the second of February.

This particular day is worth noting in Irish intellectual history. In the first place it is Saint Brighid’s Day, the first day of spring, when, according to Irish-speaking people, the sun “takes a cock’s step forward.” Saint Brighid was the patron of poets. James Stephens’ birthday is on the second of February; Thomas MacDonagh’s also fell on the same date. The fact that James Stephens and he have the same birthday is of enormous interest to Joyce. I do not know that he has any belief in any system of astrology, but I know that he is very much influenced by correspondences which seem to disclose something significant in man’s life. The whole of Ulysses is a vast system of correspondences. “Signatures of all things I am here to read,” Stephen Daedalus muses as he walks along the strand, “seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot.” The “signatures” are to be read, not only in the still life along the seashore, but in all sorts of occurrences. The fact that he and James Stephens have the same birthday, have the same first name, that they both have two children, a boy and a girl, and that the hero of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man who is also a figure in Ulysses is named Stephen, is not only of great interest but of extreme importance in Joyce’s mind.

James Joyce, because of the state of his eyes, reads very little nowadays, and so it is a surprise to find that the conversation has turned to literature. He speaks of Henry James, who he thinks has influenced Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. He praises Portrait of a Lady, dwelling with much delight on the presentation of Isabel Archer. He says that he has taken up Madame Bovary again recently, but found the narrative part tedious. For Yeats’s poetry he has a high regard, and mentions that, in collaboration with an Italian poet, he did a translation into Italian of “The Countess Cathleen” (it will be remembered that it was the lyrics in this play that possessed the mind of young Stephen Daedalus at a sorrowful time of his life). And having spoken of Yeats he goes on to speak of some other Irish writers. George Moore gave him one of his recent books; Joyce was sorry that the book was not Esther Waters, which he likes. I thought that as a Dublin man he would have a share in that city’s veneration for Swift. He has nothing of it. “He made a mess of two women’s lives,” he says. I speak of the intensity that is in passages of Swift’s writing. “There is more intensity,” Joyce says, “in a single stanza of Mangan’s than in all Swift’s writing.” Then I remember that the earliest prose of Joyce’s which I read was an essay on Mangan; it had appeared in the college magazine while Joyce was a student. I am delighted to hear this European master praise a poet who is so little known outside Ireland. He does not think that the patriotic anthem “Dark Rosaleen” is Mangan at his best. He praises “Kathleen-ni-Holohan,” “The Lament for Sir Maurice Fitzgerald,” “Siberia,” and two less known poems which are described as translations—the epigram that begins “Veil not thy mirror, sweet Amine,” and a poem of exile that has for a beginning “Morn and eve a star invites me. One imploring silver star.” He praises Goldsmith, too, especially the Goldsmith of “Retaliation,” quoting with great delight the lines upon Burke:

whose genius was such

We scarcely can praise it, or blame it too much;

Who born for the universe, narrowed his mind.

And to party gave up what was meant for mankind.

Though fraught with all learning, yet straining his throat

To persuade Tommy Townshend to lend him a vote.

He praises Goldsmith for his human qualities. “He was unassuming,” he says. For Joyce thinks it is a virtue in a man to make no disturbance about what he does or the life he has to live. “What is so courteous and so patient as a great faith?” he asks in his youthful essay on Mangan, and perhaps it is because they are indications of this great faith that he praises modesty and courtesy in certain men.

In the evening I see James Joyce again: it is at a dinner which is a birthday celebration. His appearance, his manner, his hospitality, have a quality which is courtly. I am reminded of an old-fashioned grace that was in a few Dublin houses of the old days where gentlemanliness was evident in appearance and discourse. James Joyce’s family is here and some close friends of the family. Miss Sylvia Beach, the American woman who published Ulysses, and Sullivan, the Franco-Irish tenor who is singing at the Paris Opera. The waiter brings a special wine which Joyce recommends to us very earnestly though he does not drink it himself as it is red. It is Clos Saint Patrice, 1920, and it is from the part of France where Saint Patrick sojourned after he had made escape from his Irish captivity. Joyce will not have it that Patrick was from the Island of Britain—he was a Gaul. He notes how the Tannhauser legend in its earliest form is attached to Saint Patrick. When he crossed the river and planted his staff, the staff flowered, and where it flowered are the vineyards of today. “He is the only saint whom a man can get drunk in honor of,” Joyce says, praising Patrick in this way. We laugh, but he insists that this is high praise. He vaunts Patrick above all the other saints in the calendar. Some of us mention St. Francis, but Joyce is no Franciscan, and he dismisses the Poor Man. We think that he may have more sympathy with the intellectual saints, the great Doctors of the Church; he declares he takes little interest in Augustine. Aquinas, then, whose esthetic Stephen Daedalus in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man accepts? But Joyce does not seem to have the veneration for Aquinas that he once had. I think he may put Ignatius Loyola high on account of the noble praise he has given to the Jesuit order in Portrait of the Artist. But he does not praise Loyola—the only saint he will praise is Saint Patrick, and we are convinced by his argument as we drink the Clos Saint Patrice. And then we hear Joyce saying very earnestly, “he was modest and he was sincere,” and this is praise indeed from Joyce, and he adds, alluding to Patrick’s confession, “He waited too long to write his Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man.”

This evening I have an instance of his genuine dismay at any suggestion that people whom he knows may be involved in anything violent. I had mentioned that after the kidnapping of a Russian general, the house I was living in had been watched by the police, for many Russians had apartments in it. I even had gone on to say that I thought the attic I had rented to do some work in was being searched for papers. Joyce was disturbed. Now he asks me about the affair, and I tell him that nothing is happening—there is no search going on now. Joyce is actually relieved to hear this. He has led the most heroic life of any writer living today; what he has accomplished could only have been done through the confrontation every day of obstacles which would have made another despair or turn back. And so when he speaks of his aversion to aggressiveness, turbulence, violence of any kind, his words are impressive. “Birth and death are sufficiently violent for me,” he says. The state for which he has the highest esteem was the old Hapsburg Empire. “They called it a ramshackle empire,” he says, “I wish there were more such ramshackle empires in the world.” What he liked about old Austria was not only the mellowness of life there, but the fact that the state tried to impose so little upon its own or upon other people. It was not warlike, it was not efficient, and its bureaucracy was not strict; it was the country for a peaceful man. Crime does not fascinate James Joyce as it fascinates the rest of us—the suggestion of crime dismays him. He tells me that one of his handicaps in writing Work in Progress is that he has no interest in crime of any kind, and he feels that this book which deals with the night-life of humanity should have reference to that which is associated with the night-life of cities—crime. But he cannot get criminal action into the work. With his dislike of violence goes another dislike—the dislike of any sentimental relation. Violence in the physical life, sentimentality in the emotional life, are to him equally distressing. The sentimental part of Swift’s life repels him as much as the violence of some of his writing.

For Sullivan he shows the most brotherly regard. It seems to me that he sees in this tenor the singer he might have been. They are men of the same age, each has won European recognition in the country where recognition in their particular art is hardest to obtain and most worthwhile—Joyce in France with his writing, Sullivan in Italy with his singing. Joyce might have had his appearance in opera or on the concert platform. When he was a student in the university and sang at one of the Feis Ceoil competitions, he was awarded a silver medal; the director of the Academy of Music sent for him and offered him free training. Later on when he was in Trieste and had the manuscripts of Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man coming back to him, he had the temptation to forsake literature and make his career that of a singer. What wasted life these ten years in Trieste were, teaching languages, receiving no encouragement as a writer, no acknowledgment! I know by the way he speaks about those days that the temptation to turn to another career must have been a bitter one.

In Paris he goes to the Opera; he goes every night on which Sullivan has a leading role. He thinks Sullivan is phenomenal in William Tell. “There are eight hundred top notes in it, including seventy of the highest register between B flat and C sharp.” It is characteristic of Joyce that he should have made this estimate. He ranks Rossini with the very great composers and puts William Tell with the greatest of the operas. He discerns in it the theme which he himself has worked out in Ulysses—the father’s search for the son, the son’s search for the father. Ostensibly the opera is about the relation of men to their fatherland; into it comes the old patriot’s relation to his son Arnold, and Arnold’s love for Mathilde, whose father is the oppressor of the fatherland, and the fugitive who is pursued by the imperial forces because he has protected his daughter from their molestation. All this Joyce makes clear to us as we sit with him at this pleasant celebration.

We drink more of the Clos Saint Patrice. What of Joyce’s relation to the country to which Patrick returned after his sojourn in France? He does not speak of it. And yet he says that he should like to live in a city that was not one of the great cities of the earth—one that has a population of about 300,000. “I go to forge a new conscience for my race,” Stephen Daedalus said as he left the city that has about that population. We have no speeches on this birthday: no one tells James Joyce (although a few of his fellow countrymen are present) that the creator of Stephen Daedalus has not failed in the labor of creating that new conscience. We know that he has not failed although we keep silence about it.

In the apartment to which we return there is jollity. George Joyce sings; Sullivan sings; James Joyce sings. He is persuaded to sing a humorous Irish ballad, “Mollie Branagan,” and he renders it with gusto; the phrasing, the intonation, are as an old ballad singer would have them. And then he sings a tragic and sorrowful country song which I have never come across in any collection nor heard from any one else except James Joyce. It is about a man who has given his life to a stranger—he may be from Fairyland, he may be Death himself. It has for burthen “O love of my heart” and “O the brown and the yellow ale,” and these refrains in Joyce’s voice have more loss in them than ever I heard expressed. He had said to me when we were at the Opera together, “A voice is like a woman—you respond or you do not; its appeal is direct,” and he said this to show that what was sung transcended in appeal everything that was written. His own voice in the humorous and the sorrowful song was unforgettable.

And now we sit at the table, two of us, and drink out of the great flagon of white wine that is there, and talk about Dublin days and scenes and people. All memories are sorrowful, and Joyce, who remembers more than any other man, has much to be sorrowful about. He faces suffering in operations on his eyes—ten already. But his thought is never personal; he thinks of friends, he plans how to serve them. Some words are said about writing. “What goes on in an ordinary house like this house in an ordinary day or night—that is what should be written about,” he says. “Getting up, dressing, saying ordinary words, doing ordinary business, eating, sleeping, all that we take for granted, not leaving out the digestive processes.” For writers who are prophetic Joyce has little regard. “It would be a great impertinence for me to think that I could tell the world what to believe or how to behave.” I think of a passage in this early essay of his on Mangan, a passage that is significant because Joyce’s mind has not changed in the time between youth and prime. “It must be asked concerning every artist how he is in relation to the highest knowledge and to those laws which do not take holiday because men and times forget them. This is not to look for a message but to approach the temper which has made the work, an old woman praying, or a young man fastening his shoe, and to see what is there well done and how much it signifies.” He thinks that too much fuss has been made about the work of recent Irish writers. “If we lift up the back-skirts of English literature we will find there everything we have been trying to do.” Every shade of meaning that any writer might want to find can be found in the English language, he says. I feel that only a man who is sustained by some great faith can speak as simply as he speaks. “In those vast courses which enfold us and in that great memory which is greater and more generous than our memory, no life, no moment of exaltation is ever lost; and all those who have written nobly have not written in vain, though the desperate and weary have never heard the silver laughter of wisdom.” So he wrote in this youthful essay which I have quoted from before, and perhaps these words hold his faith.