The snake had been eating the crow’s eggs every day for weeks. “So she taught him a lesson,” twelve-year-old Taj said, pointing to the skeleton, the ribs of the snake curled up like a question mark. “You know, crows never forget a face.”

I asked him how he knew that.

“My mother told me.”

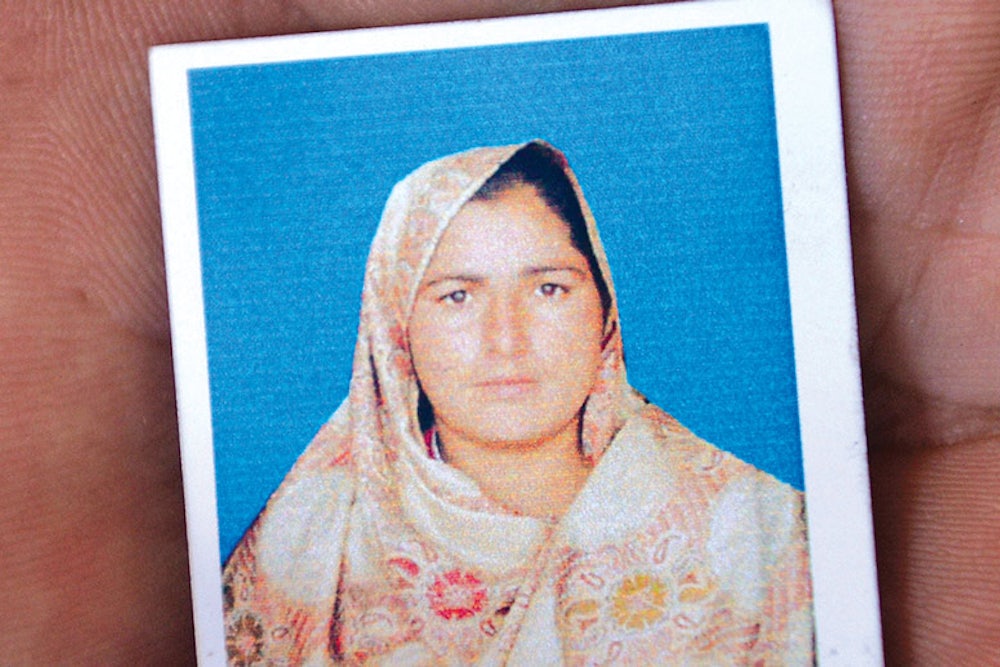

The woman Taj called mother was dead. Farzana Parveen had been bludgeoned to death with bricks by members of her own family, including her father. They killed her because she had fallen in love with Taj’s father, a widower named Muhammad Iqbal, and married him. She was 25 years old and three months pregnant.

Honor killings are so common in Pakistan that they usually only rate a brief mention in the local media. In 2013, 869 such cases were reported, according to the country’s Human Rights Commission, although the true figure is probably higher. But Farzana’s death stunned people around the world, perhaps because it seemed like a dark tale of thwarted love, or because her murder occurred in the day time, before dozens of onlookers, near the High Court in Lahore. Two days and a post-mortem later, I followed Farzana’s body back to her final resting place in the tiny village where she had lived in a mud-brick house with Iqbal during their five-month marriage.

In the hours after the funeral, no one spoke very much. There was no mention of god, or god’s will. There was no wailing, no hysteria, and no chest-thumping, gestures so characteristic of South Asian mourning. No one from her family was present. Farzana had come to this house with nothing and she had left it with nothing: This did not seem like a memorial fit for a woman who had died for love.

Iqbal stood by the freshly dug grave, his long, hawkish face revealing no emotion in particular. Only a few of the rose blossoms on the burial mound were still red. He told me that, when Farzana’s family attacked her, he hid under a car. “It was my duty to save her, and I let her down,” he said.

He had liked Farzana since she was barely a teenager. Her family’s land bordered his own, and one day he saw a girl working in the fields, dressed in a white voile shirt and a flimsy white shawl that covered her head, “like a fairy.” At the time, he was already married to Ayesha Bibi, a woman his parents had chosen for him and who had borne him five children.

For years, Iqbal says, he yearned for Farzana, and sometimes she would give him waggish glances as she milked a cow or stacked the hay. In 2009, he finally approached her. By then, Farzana was 20; Iqbal was almost 40.

They began a surreptitious courtship, using a mobile handset he gave her. “During the day, she would keep the phone hidden under piles of bedding and take it out in the evening once everyone was asleep,” Iqbal said, smiling. “We talked through the night. Every night. But she never let me touch her until we were married.”

And then his wife found out. One day, arms spread-eagled across the doorway, Ayesha refused to let her husband leave home to meet his sweetheart. “She was hysterical,” Iqbal said. “She was screaming and abusing me ... like she was mad.”

Iqbal reached for Ayesha’s neck. “I held her by the neck and I strangled her, and then I pushed her and she fell,” he said, pausing for several seconds between words. “She should have gotten out of my way.”

That was how Iqbal came to be a widower.

Iqbal was released on bail, but the murder case dragged on for almost four years. He finally won his freedom by invoking an Islamic law that allows victims’ families to decide the fate of convicted criminals. In this case, Ayesha’s next-of-kin were the three sons and two daughters she had with Iqbal. They forgave their father and he moved back home.

As a widower, Iqbal was free to remarry, and in 2013, he and Farzana got engaged, after Iqbal agreed to pay her family $800 and some gold as a dowry. But two months later, her father demanded an extra $1,000 for her hand. When Iqbal said he did not have the money, Farzana’s father called the engagement off. In January, the couple eloped and married in court.

Iqbal says that he and Farzana shared a quiet happiness, for a while. He recalled the songs she loved to sing and her simple requests for cold cream or new shoes. Her step-sons told me the names of the birds and trees that she had taught them. I asked if Farzana had helped them with their homework. “She could just sign her own name,” nine-year-old Faisal explained. “That was all she knew.”

“When I asked Farzana if she wanted children, she would say, ‘I already have five children,’ ” Iqbal added. “But sometimes when I would push her, she would say, ‘I just want one more son with your green eyes.’ ” In February, she became pregnant.

Farzana’s family, however, was incensed that they had been robbed of a daughter without being paid the correct price. They lodged a kidnapping case against Iqbal and submitted documents alleging that Farzana was already married, to her cousin, Mazhar. In Pakistan, if a woman remarries without annulling her first union, she can be jailed for up to seven years.

Iqbal protested that the documents were forged. But the police, he said, started raiding their house almost every week. Iqbal said that he even sent Farzana to a women’s shelter for a month to protect her. Soon after she returned, they were attacked by more than a dozen men on motorbikes. When they went to Lahore for a court hearing on May 27, Farzana’s family was waiting for them outside the courthouse.

Iqbal said that, as one of her cousins hit Farzana with a brick, she screamed: “Don’t kill me! Take money, don’t kill me.” Five other men joined in. Iqbal begged the police for help, but then the screaming stopped.

In late June, I went to visit Farzana’s family at the Lahore offices of the lawyer who is defending them against the murder charges. Their account of her death is very different from Iqbal’s.

“Iqbal and his son came armed and took her away,” Farzana’s elder sister, Khalida, told me. “He fell for her and knowing that she was already someone else’s wife, he and his hooligan son came with big guns to take her away.”

Khalida sat cross-legged on a chair, balancing two small children on her knees. She played with a large golden nose-pin, her voice breaking as she described how her sister had grown afraid of Iqbal—“afraid he would kill her like he had killed his first wife.” It was Iqbal, she said, who had killed Farzana, not her brothers and father. “She saw us outside the court and ran toward us,” Khalida said. “Iqbal’s son Aurangzeb fired a shot which hit her ankle. As the crowd gathered, Iqbal hit Farzana on the head with a brick. Twice. That was all it took.”

When I visited the scene of the attack, on a busy avenue in a stately part of Lahore, it was raining. An empty wooden crate, the kind used to store mangos in summer, marked the place where Farzana died. The crate had been turned upside down and someone had placed a brick on top of it.

The owner of a small kiosk told me he had witnessed the attack. “We saw a woman running and then there was a gunshot and people quickly gathered all around,” he said. “She was already dead when the crowd dispersed.”

And so I called Iqbal to ask him whether he had killed his second wife. He laughed on the other end of the line. “If I wanted to kill her, why would I do it outside the high court in front of so many people?” he asked. “I would have done it when she lived with me for so many months.”

There was only one part of the family’s version of events that I was able to verify, concerning their claim that Farzana had previously been married. In Lahore, Mansoor Afridi, the lawyer representing Farzana’s family, showed me a video of a typically exuberant wedding in rural Pakistan.

Men dance next to a white car decorated with red roses and pink streamers. The bride, her face covered by a heavy orange veil embroidered with gold and blue, keeps her eyes dutifully on the floor. The newlyweds are about to enter their home, but first, the groom’s family must give the bride some money. A round of playful negotiations begins. When the mother-in-law tries to put two hundred rupees in the bride’s hand, she chuckles and flashes five fingers through her veil.

“She wants five hundred rupees!” the girls around her holler. “Or five thousand!”

A young man pipes up, “I think she just means five rupees.” Everyone bursts out laughing, including the bride.

Next, the video cuts to the newlyweds seated on a bed of red and orange cushions. As relatives get their pictures taken with the couple, the bride stares straight into the camera. She is wearing rose-pink eye shadow. Her lipstick has rubbed off from a long day of celebration, but there is a soft smile on her face still.

The video is not high quality and the woman is younger, but the image is clear: It is Farzana.

In Disgrace, J.M. Coetzee’s novel set in post-apartheid South Africa, a white woman is gang-raped by three black men. Later, she asks: “But why did they hate me so? I had never set eyes on them.” Her father answers: “It was history speaking through them. ... It may have seemed personal, but it wasn’t.” In Pakistan, history—in the form of the elemental laws of the family, the sect, the religion—often speaks through the mutilation and murder of women like Farzana.

I thought back to the quiet scene of her mourning. I had asked Iqbal if he expected justice for his wife, and he was silent for a moment. “You are only here because she was killed outside the court,” he said finally. “If she had been killed on a street corner in this village, would you even have come here? Who cares that one woman is dead?”

Soon afterward, Iqbal was called away, and I went to talk to Taj and Faisal, who were playing by the house. They said they were having trouble sleeping, because they had grown so accustomed to sleeping next to Farzana. I asked Taj if he would forgive her family for killing her, like he had forgiven his father for killing his birth mother. “Never,” he said, sounding almost adult-like in his resolve.

Not far away, a crow was walking around the bones of the snake he had shown me earlier, bobbing from one foot to the other. “Look, that crow is back,” Taj said. “I told you, my mother said they never forget.”

On July 5, a court indicted Farzana’s father, two brothers, a cousin, and the man who claims to be her first husband for Farzana’s murder. That evening, I went back to the place where she died, but the crate-and-brick memorial was no longer there.