This story first appeared in Eight by Eight magazine's World Cup issue.

ICON (also ikon) 1. A devotional painting of Christ or another holy figure, typically executed on wood and used ceremonially in the Byzantine and other Eastern Churches. 2. A person or thing regarded as a representative symbol or as worthy of veneration: “this iron-jawed icon of American manhood.”

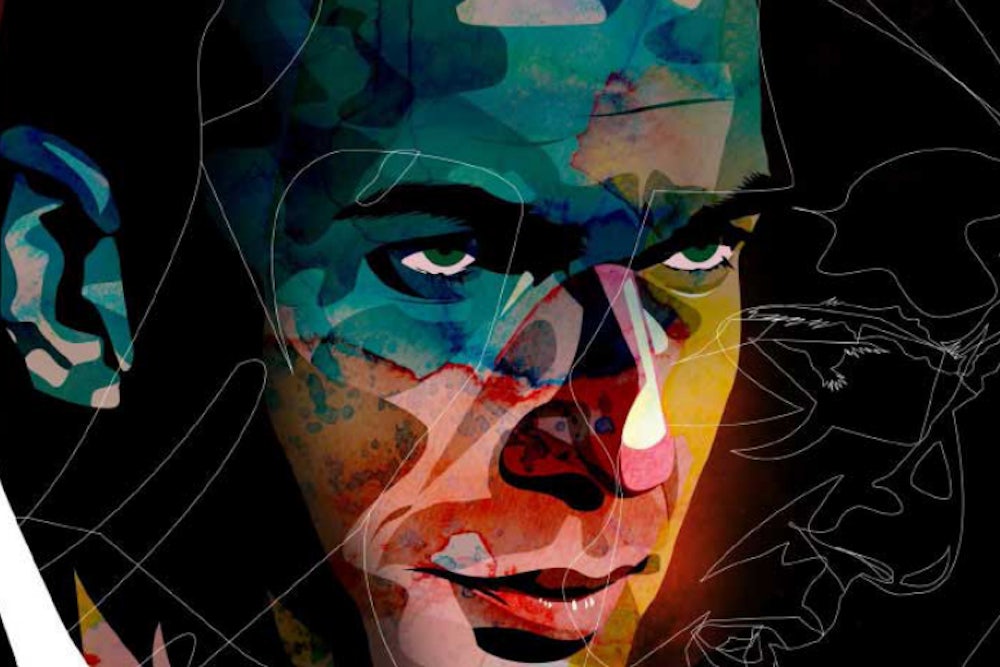

So says the Oxford English Dictionary. “Zinedine Zidane” would be a tempting addition: “regarded ... as worthy of veneration”—yes, certainly. When your face is beamed on the Arc de Triomphe on the night of France’s greatest-ever sporting exploit, of which you’ve been the undoubted hero, how could you not be?

To acknowledge Zidane’s iconic status does not necessarily mean, however, that it was bestowed on him by a nation united in gratitude, as I was recently reminded in a Paris cab. Each time I step in a taxi, I ask myself the same question: “Is this one a talker?” The driver I’d just hailed outside my radio station was definitely a talker. And what he wanted to talk about was Zinedine Zidane.

It was a well-rehearsed spiel. It started with “I come from Algeria ...” I was waiting for the “but ....” “But I am a Kabyle,” he said. Kabyles are the indigenous people of the Maghreb, part of the Berber ethnic group, who were subjected to Arabization by the Muslim colonizers from the seventh century onward but have managed to retain their language and their culture. “We’ve given a lot to France,” he said, “and I’m proud of it.” He reeled off an impressive list of people who had enriched our national life. Some say that no less than a third of France’s 6 million citizens of Algerian heritage are Kabyles—actors, singers (did you know Edith Piaf had a Berber grandfather?), scientists, journalists, politicians. But Zidane, “Ah non! And I’ll tell you why.”

The why had nothing to do with the Materazzi headbutt in the 2006 World Cup final, or the vicious stamp on Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed al-Khlaiwi in France’s second game of the 1998 tournament, or the 14 red cards the country’s favorite sportsman collected in an otherwise stellar career. It had to do with what my driver called the “cowardice” of a man who’d forgotten where he’d come from.

“If only he’d spoken!” said the driver. “But he said nothing.”

Spoken about the bloodbath of Algeria’s “black spring,” he meant, three months of government-sponsored thuggery, rape, and violence in 2001, which resulted in the deaths of at least 120 Kabyle demonstrators who’d taken to the streets after the murder of a high school student in a police station.

Marseille-born Zidane, whose parents Smaïl and Malika both hail from Kabylia, kept his own counsel when asked to comment on the tragedy. In 2001, this could easily be forgiven. Zizou was at his peak. He did not wish to see his name and reputation used by opportunistic politicians. He’d refused to be drawn into the pseudo-debate about “integration” and “communitarism” after the victory of Les Bleus in 1998, when the whole country—or so it seemed—became obsessed with the fantasy of a new “rainbow nation” (a delusion that didn’t last long).

By the summer of 2006, however, Zidane had retired, and on July 22, 13 days after Italy beat France on penalties in his last official game, an open letter signed by prominent members of the Kabyle diaspora was addressed to Materazzi’s nemesis/ victim. This touching, somewhat naive document, endorsed by 18 Kabyle and Berber organizations, did not elicit a response.

Unless this was the response: five months later, on Dec. 12, Zidane walked out on the tarmac of Algiers airport and was engulfed by a near hysterical crowd. The plane that had brought him to the land his ancestors came from—but which he knew little about—had been chartered by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who’d masterminded the brutal suppression of the Kabyle uprising five years earlier. The terms of Bouteflika’s invitation letter verged on the grotesque. The (elected) dictator saluted the “beautiful, courageous, exceptional career that you [Zidane] have been able to build with pugnacity, wisdom, audaciousness, and ponderation, above all with incomparable fair play.” To wit, referring to the “Materazzi moment,” in which Z.Z. had “first and foremost reacted as a man of honor.” Thus spoke a man who knew all about honor and who opened the doors of his presidential palace to the Zidane family. Zidane’s mother judged him “a good communicator.

Zidane didn’t disappoint his host. He kept mum about that nastiness in 2001. Constantly accompanied by Bouteflika’s bodyguards, he emoted about his “return” (which was more like a first coming), and he pressed the flesh when he had to, spending one whole hour in his father’s village—in five days. It should have been three hours, but schedules are subject to change when you’re a superstar. Too bad for the guys who’d been preparing couscous for 50 people since dawn, though they might not have minded that much: they were happy to see their cousin (one newspaper claimed there were 200 such cousins in attendance that day), their hero. He was whisked away, not his fault. He’d made the effort. That’s all that mattered. But made the effort for what, for whom? Repression? Bouteflika?

By then, my cabbie had gone to 11 on the 1–10 indignation scale. He saw me nodding in the mirror. I was thinking of Zahir Belounis, the French-Algerian footballer who was kept against his will in Qatar for 19 months, a casualty of the notorious kafala system. Belounis had made a public appeal to Qatar 2022’s most prominent ambassadors, Pep Guardiola and Zinedine Zidane: Help me, please. Help me get out of this hell.

Guardiola let it be known that he was not au fait with the particulars of Zahir’s situation and stopped at that. I searched for a reaction, any reaction, from Zidane’s camp and could find none. To be fair, you’d have to say that it couldn’t have been that easy for Zizou to react. He’d been paid a lot to sponsor the Qatari bid. It was reported that the price for his endorsement was a cool $15 million (plus, if Qatar won the bid, $1 million a year until the competition took place). This was subsequently denied, albeit not very convincingly. All money was paid to the footballer’s foundation.

Regardless of the figures, the fact remained: Zidane had cashed in, as Guardiola, Ronald de Boer, Gabriel Batistuta, Roger Milla, and others had done. There is nothing scandalous in that. David Beckham’s support for England 2018 was not solely motivated by patriotism; his “soccer schools” would have benefited at least indirectly from awarding the tournament to the English.

What grated is what Zidane said to promote the cause of his new benefactors and, especially, what he said after they drew FIFA’s winning lottery ticket. “Beyond the victory of Qatar, this is especially a victory for the Arab world and the Middle East,” he said. “This is what touched me most. It’s nice to have something new. It was nice to show that football belongs to everyone. They said that Qatar was less likely [to win] because it is a small country. But Qatar represents the Arab world, and today that is the logic that has prevailed. I am proud of this victory.”

I wanted to scream, “But, Zinedine, you are not an Arab! Arabs have been beating the shit out of Kabyles for 13 centuries. You don’t even speak the language. You’re not a practicing Muslim, if you want to use the—fallacious—ummah argument. Just say it as it is, for goodness sake. We’ll still love you.” But I’m afraid this argument won’t take anyone very far.

Emmanuel Petit said, “Zidane and myself, we’re different. We’ve got nothing to say to each other. You can’t pretend you’re helping those who are in need when you’re serving the cause of the big bosses who are registering record profits without redistributing them. When you acquire a dimension like his, which is beyond reason, it’s good to state your own convictions from time to time. He’s become untouchable.”

Quite true. But Zidane doesn’t do convictions. Convictions don’t do much for business. And business is something that Zidane cares a great deal about.

In 2008, French journalist, Besma Lahouri, who has since written a biography of France’s former first lady Carla Bruni, as well as a quite entertaining account of President Hollande’s ménage à trois, published Zidane: Une Vie Secrète (Zidane: A Secret Life). It caused more stir before it was published than when reviewers got hold of an advance copy and delivered their—generally unfavorable—verdicts.

The author’s flat had been burgled twice before the final version was delivered. Lahouri’s laptops were stolen on both occasions. This must be hot shit, we thought. People fantasized about what Lahouri had dug out. All these rumors about Zizou’s private life—performance-enhancing drugs at Juventus (and elsewhere) ... ooh. When it became clear that Lahouri hadn’t found any smoking gun—in a country where libel law pretty much favors the attacker—interest in her work dwindled, which is a pity.

It’s not that this book represents a landmark in football or investigative writing. Critics chose epithets such as “labored,” “repetitive,” and “clumsy” to describe its style. No bombshells. No ooh factor. But it showed a Zidane far removed from the saintly character who, alone among the victors of 1998, had entered the national pantheon and regularly topped the list of most loved personalities in France.

How Zizou acquired this status is fascinating. The balletic beauty of his game and his ability to be at his best when it most mattered (though less often than his hagiographers have suggested) were the foundation of his extraordinary popularity. He wouldn’t have taken his seat among the gods on Olympus if he hadn’t scored those two headers against Brazil in July 1998. But this couldn’t explain how he shot into that heroic dimension—not a megastar, a metastar—in a country that cares far less about football than any of its neighbors do.

What attracted people was his shyness; his winning, self-deprecating smile; his charm ... what my mother called his gentillesse, which is far more than kindness. His looks too. He was handsome but seemingly unaware of it; this wasn’t the kind of footballer you’d imagine preening for hours, transforming his body into an object of desire. In fact, he’d never looked a natural athlete, even after bulking up impressively while playing in Serie A. The early baldness, which he did nothing to hide, suited him and was yet another proof of his normality. He clearly loved his children; he loved children, period, as he’d shown in his work for several charities, including his own foundation. The very fact that he hardly ever gave interviews and stayed clear of the celebrity circus was proof of his humility. He was far more than the ideal footballer; he was the ideal son, father, husband, son-in-law. And he was a second-generation “immigrant” (a Kabyle, to boot—which, in the twisted collective psyche of mainstream, Caucasian France, made him some kind of super-Arab) who presented an unthreatening image of immigration. Ah, if only they could all be like Zizou!

Lahouri’s book, for all its imperfections, scratched the veneer of this construct to reveal a far less seductive character, a manipulator who had carefully built, exploited, and protected the cult of Zidane to gain money and power. It was a remarkable ascent for a scrawny kid from an impoverished Marseille banlieue who’d left school at 15 and, even before he retired, grown to enjoy the friendship of business tycoons like Franck Riboud (chairman and CEO of the Danone Group) and Jacques Bungert (co-chairman of the Young & Rubicam advertising agency and the Courrèges fashion house). Riboud even suggested—in July 2006—that the footballer who’d promoted his brand since 2001 could be given a place on the board of his multinational. François-Henri Pinault, the billionaire owner of the Kering Group, who sometimes lent his private jet to the traveling footballer when he played for Real Madrid, is another such connection.

These are the kind of links that jarred Emmanuel Petit. With a ball at his feet, Zidane was a poet. Away from the game, he became a businessman motivated by self-interest. There is nothing untoward or reprehensible in this; in truth, Zidane could serve as a case study of the modern super-sportsman, the footballer as brand. We might deplore this, turn up our noses, and long for a bygone age when sport was about glory (or so we like to believe). But can it be held against him that he’d exploited a system that pre-existed him?

Why then do I find it so difficult to reconcile those two sides of his persona? Perhaps because they are inextricably intertwined and ridiculous as it may sound, the idea that football is not an end in itself and could be used as a tool for self-promotion remains hard to swallow, especially when the footballer won our love for the sheer beauty of his play. This is not why we watch it, is it?

In April 2005, filmmakers Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno installed 17 synchronized cameras around Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu Stadium. All those cameras would be trained on Zidane for the duration of a La Liga encounter between Real Madrid and Villarreal. This was not the first time he had collaborated with documentary makers: In 2002, his friend Stéphane Meunier put together a celebratory portrait, Comme Dans un Rêve (As in a Dream), which met with only modest success in France, the 2002 World Cup having been a nightmare for both the national team and its injured playmaker.

Gordon’s and Parreno’s film, Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, belonged to a different genre. No other player has been the subject of such an ambitious and expensive project. The aim was to create not only a work of art but a masterpiece. The result is an overblown, over stylized creation laden with the kind of video trickery familiar to any MTV viewer: 91 minutes of advertising, the product being Zidane.

Compare this with the film that inspired its format, Helmuth Costard’s 1971 Fußball Wie Noch Nie (Football as Never Before), shot in September 1970 with eight 16mm cameras, which focused on George Best for the duration of a 2-0 victory by Manchester United over Coventry City. For all its knowing avant-gardism, Costard’s filmic essay, shot with Best’s assent, has aged rather better than Gordon and Parretto’s. It’s hard not to see Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait as an exercise in self-aggrandizement, vetted by the film’s hero (who got sent off at the end of the 2-1 win) as an effort by his advisers to reinforce a lucrative brand, rather than the celebration the player’s art deserved. In 2007, there would be yet another documentary, again directed by Meunier, Le Dernier Match, co-produced by Zidane himself.

File that one under overkill. None of this would matter, maybe, if that facet of Zidane, architect of his own mythology, could be separated from the genius who made us gasp on a football field. But the manipulator cannot be set aside that easily. Back in 2004, when his power to shape games appeared to be on the wane, it was clear that France was blessed with another outstanding talent to whom he could pass the baton. Thierry Henry was nearing the apex of his career. He’d had a superb Confederations Cup the previous year (a tournament Zidane took no part in) and was at last showing signs that he could replicate his consistent form for Arsenal with Les Bleus, for whom he’d shone more fitfully.

It had become a subject of particular frustration that Zidane and Henry seemed unable to dovetail on the pitch together. The latter’s comments that France was not playing to his strengths (true, if clumsily expressed) hadn’t gone down well; to say this was to question the contribution of the untouchable Zidane. More damagingly, there were rumors (as early as 2002), amplified in the media, that a clan of Gunners (comprising Patrick Vieira, Robert Pirés, Henry, plus unnamed accomplices) was plotting against Zizou.

To those who didn’t buy into this conspiracy theory (I was one), this looked suspiciously as if Zidane himself was not too happy about seeing the young upstart projecting too long a shadow on his patch. Why was it that the chief creative force of Les Bleus appeared incapable of exploiting Henry’s pace and sharpness of movement? The statistics were incomprehensible. Zidane never provided an assist for the serial Premier League and European Golden Boot winner. Never. By the 2006 World Cup, not one pass from France’s No. 10 to its No. 12 had resulted in a goal in the 51 games they’d played together. (That finally came to an end in the 1-0 victory over Brazil in the quarterfinals, when Henry volleyed in Zidane’s free kick.) In the meantime, Zidane had supplied assists to no fewer than 12 different French teammates. Symptomatically, Henry was considered the party at fault, as it was unthinkable that Zidane could freeze out a fellow player to protect his aura.

I’d like to believe that this was just a freaky coincidence, two planets orbiting around different suns. I’d like to believe it, but I find it hard to do so.