The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) publishes a weekly webzine, The Islamic State Report. The latest issue is headlined “Smashing the Borders of the Tawaghit.” (“Tawaghit” are non-Muslim creations.) ISIS, citing the Sykes-Picot Treaty of 1916 between the British and French, boasts that it is destroying the “partitioning of Muslim lands by crusader powers.” That may seem like a quixotic task for a relatively small band of irregulars, but in trying to redraw the map of Iraq and Syria, ISIS has hit upon a weak link in the chain holding the nations of the Middle East together.

It is easy to blame what is going on in Iraq or Syria on dictators and terrorists, but these various bad actors are bit players in a drama that goes back at least to World War I. What is happening is that the arrangements that the British and French created during and after World War I—which established the very existence of Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Jordan, and later contributed to the creation of Israel—are unraveling. Some of these states will survive in their present form, but others will not. The United States may, perhaps, be able to slow or moderate the process, but it won’t be able to stop it.

If you look at a map of the Middle East in 1917, you won’t find Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, or Palestine. Since the sixteenth century, that area was part of the Ottoman Empire and was divided into districts that didn’t match past or future states. The British and French created the future states—not in order to ease their inhabitants’ transition to self-rule, as they were supposed to do under the mandate of the League of Nations, but in order to maintain their own rule over lands they believed had either great economic or strategic significance.

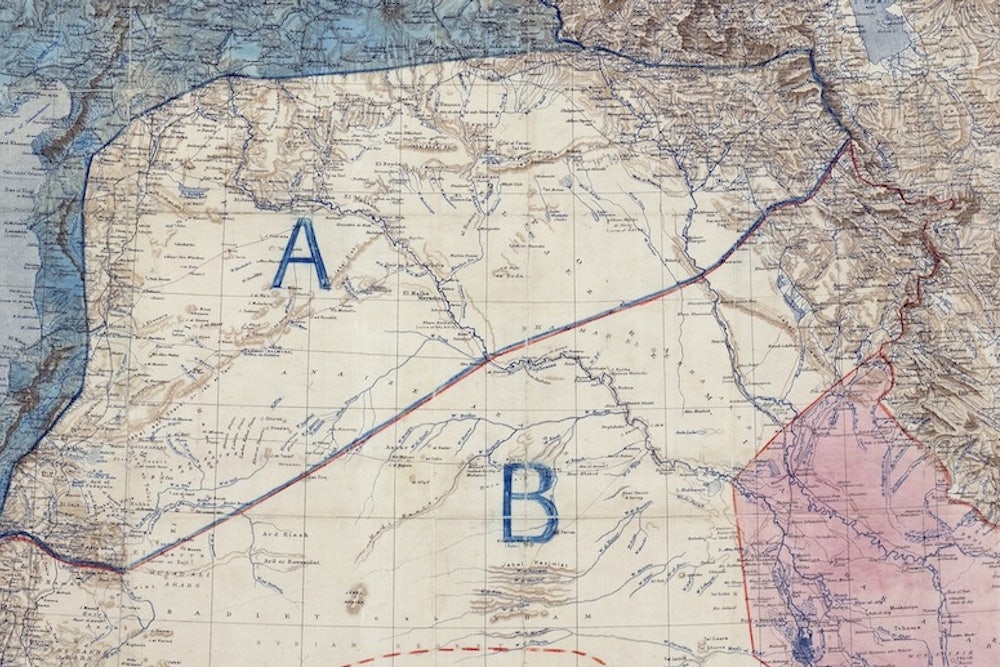

In 1916, as The Islamic State Report indicates, the French and British agreed to divide up the Ottoman Middle East in the event that they defeated Germany and their Ottoman ally. The French claimed the lands from the Lebanese border to Mosul; the British got part of Palestine and what would be Jordan and Southern Iran from Baghdad to Basra. After the war, the two countries modified these plans under the aegis of the League of Nations. At San Remo in 1920, the British got the territory that in 1921 they divided into Palestine and Transjordan and all of what became Iraq. (France gave up northern Iraq in exchange for 25 percent of oil revenues.) The French got greater Syria, which they divided into a coastal state, Lebanon, and four states to the east that would later become Syria.

These lands had always contained a mix of religions and ethnicities, but in setting out borders and establishing their rule, the British and French deepened sectarian and ethnic divisions. The new state of Iraq included the Kurds in the North (who were Sunni Muslims, but not Arabs), who had been promised partial autonomy earlier by the French; Sunnis in the center and west, whose leaders the British and the British-appointed king turned into the country’s comprador ruling class; and the Shiites in the South, who were aligned with Iran, and who had been at odds with the Sunnis for centuries. After the British took power, a revolt broke out that the British brutally suppressed, but resentment toward the British and toward the central government in Baghdad persisted. In the new state of Transjordan (which later became Jordan), the British installed the son of a Saudi ruler to preside over the Bedouin population; and in Palestine, it promised the Jews a homeland and their own fledgling state within a state under the Balfour Declaration while promising only civil and religious rights to the Palestinian Arabs who made up the overwhelming majority of inhabitants.

In the new state of Lebanon, the French elevated the Christian Maronites into the country’s ruling elite, and created borders that gave them a slight majority over the Shia and Sunni Muslims. In the land that became Syria, the French initially separated the Alawites (from whom the Assad family would descend) and the Druze into their own states and empowered the urban Sunni Muslims in Damascus and Aleppo. During World War II, Syria was finally united in the state that exists today.

From the beginning, these newly created states were engulfed by riots, revolts, and even civil war. Most of the early revolts were directed against the colonial authorities, but after World War II, when these states won their independence, the different religious denominations, ethnicities and nationalities fought each other for supremacy—the Kurds, Sunnis, and Shiites in Iraq, the Jews and Arabs in Palestine (and later Israelis and Palestinians), the Maronites and Muslims in Lebanon, and the Alawites and Sunnis in Syria. The resulting strife was not a product of the Arab character or of Islam. As University of Oklahoma political scientist Joshua Landis has noted, the turmoil in these lands was very similar to that which took place, and is still taking place, in the various states constructed and deconstructed in Central and Eastern Europe in the wake of the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires and Germany’s defeat after World War I.

In Lebanon, the turmoil has been almost continuous. Lebanon still lacks a stable governing authority. In Iraq and Syria, inter-sectarian and inter-ethnic conflict were temporarily stilled by dictatorships that severely repressed any hint of revolt. Israel used its military to contain the conflict with Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and in Gaza. But in Iraq and Syria, the lid of repression came off, as a result of the American invasion in 2003 that ousted Saddam Hussein and as a result of the Arab Spring spreading to Syria.

Theoretically, the lid could be reimposed in either country by a brutal dictatorship, but it looks increasingly unlikely that either Iraq’s Nouri al-Maliki or Syria’s Bashar al Assad will be able to impose order on their deeply divided states. What’s most likely is that Iraq and Syria, like the former Yugoslavia, will splinter into separate states. Iraq’s Kurds are likely to be the first to go. The danger for the United States does not lie in the breakup of these states, but in the empowerment of terrorist groups like ISIS that could threaten the region’s oil output and use their base in lawless areas to spread disorder and terror elsewhere, including the West. In the long run, the United States has to worry about instability in a region that is so important to the world economy and that will eventually have more than one nuclear power.

In the past, the United States has been of two minds in dealing with disorder in the Middle East. The United States generally backed kings and dictators as long as they were friendly to the United States. But under George W. Bush, the United States sought to create a democratic revolution in the region by ousting Saddam. That proved to be futile and dangerous, but the Obama administration appeared to endorse those objectives in 2011 in the wake of the Arab Spring revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. At present, the administration’s strategy seems ad hoc—enthusiastically embracing Egypt’s repressive government, while calling for Bashar al Assad’s removal.

What the history of the region suggests is that—to put it in somewhat vague terms—things are going to have to sort themselves out. The people of this region will have to learn how to govern themselves through experience, as the people of other nations, including the United States, have had to do. Outside of Israel, where the United States can exert pressure to end the occupation, but is often reluctant to do so, American influence is very limited. There will be more dictators, but also fledgling democracies. And American objectives will probably have to be limited to preventing terrorist attacks on the West, the interruption of oil supplies, and the subversion by groups like ISIS of the more stable regimes in the region. Its principal tools are diplomacy (that must include Iran), sanctions, and as a very last resort, narrowly targeted armed intervention. ISIS won’t get its Caliphate, but the United States won’t get its United States of Arabia either.