Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned by the Nazis by Michael Haas (Yale)

In 1909, in a best-selling book called Contemporary German Music, the respected Munich critic Rudolf Louis diagnosed Gustav Mahler’s problem: “What I find so fundamentally repellent about Mahler’s music is its axiomatic Jewish nature. If Mahler’s music spoke Jewish, I perhaps wouldn’t understand it, but what is disgusting is that it speaks German with the Jewish accent—the all too Jewish accent that comes to us from the East.” Still worse, Louis added, was the composer’s masquerade: “Mahler has no idea how grotesque he appears wearing the mask of the German Master, which highlights the inner contradictions that make his music fundamentally dishonest.” Anticipating critics, Louis calmly dismissed the charge of anti-Semitism as exaggerated hysteria—but his ideas and his rhetoric were directly descended from, if not a close paraphrase of, Richard Wagner’s infamous anti-Semitic tract Jewishness in Music, written sixty years earlier. Far from an isolated rant, Louis’s writing represented a thread of Wagnerian myth running through the very fabric of modern musical thought.

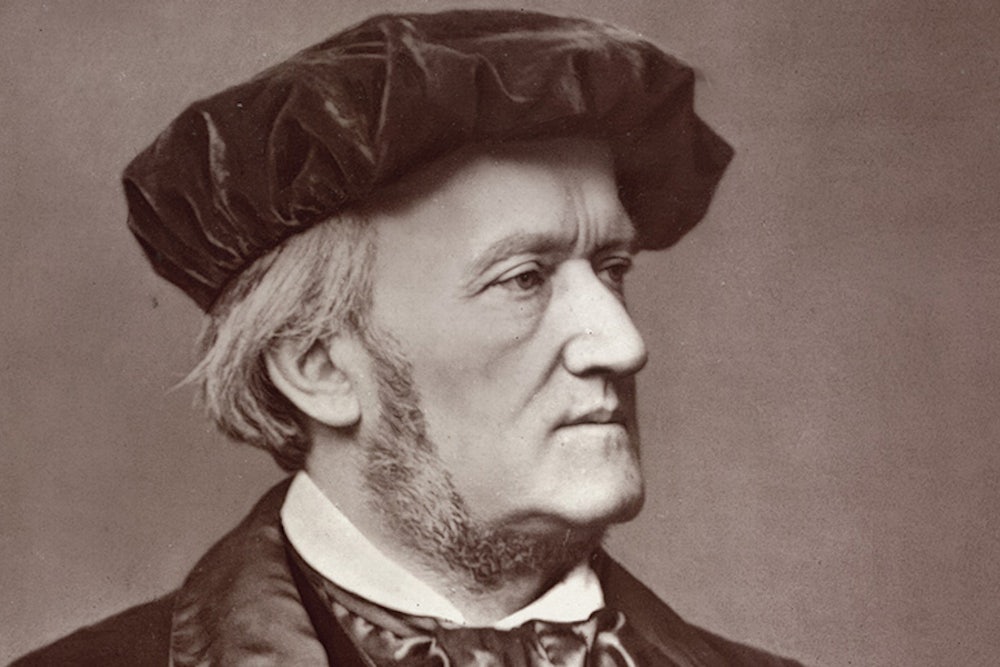

What are we to do with Wagner’s anti-Semitism? The recent Wagner anniversary has brought a predictable amount of equivocation and hand-wringing about the German master’s role in the history of hate. We know by now not to read history backward. A nineteenth-century composer who died in 1883 cannot logically be accused of personal complicity in a twentieth-century genocide. Yet that does not mean that the broader question of his responsibility for the spread of modern anti-Semitism can be simply ignored. The issue cannot be brushed aside merely by reference to the fact that, as Daniel Barenboim and other commentators relish pointing out, Wagner loved a handful of Jews (albeit conditionally) and that many Jews (even Zionists) loved Wagner. The fact that there were and are Jewish Wagnerians is not a coherent answer to the question of Wagner’s prejudice against the Jews. Irony is no disclaimer. Nor, conversely, does the musicological obsession over whether Wagner secretly encoded anti-Jewish tropes into his compositions matter much beyond the precincts of academia. The real legacy of Wagner, one with which we are still living today, is nothing less than the sweeping imprint of racial ideology across the length and breadth of modern classical music.

Michael Haas makes this case powerfully in his important book. While the title misleadingly suggests a study devoted to the Holocaust era, Haas instead paints a group portrait of two generations of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Central European Jewish composers and critics locked in tortured relationships with their own racialized selves. His is an erudite survey, chock full of choice quotations mined from diaries and letters and studded with keen insights about the social politics of Austro-German music. It is also a return visit for Haas to the composers he previously documented as producer of the pioneering Entartete Musik record series of the 1990s. That innovative project recovered the works of composers who, before 1933, stood at the pinnacle of German music, only to be murdered or exiled in the Nazi era. This volume, by contrast, seeks a broader measure of historical understanding. By extending the chronological span back into the nineteenth century, Haas does more than simply write a history of Hitler’s musical victims. He convincingly refutes the claim that Wagner’s disturbing indiscretions only turned truly dangerous once the Nazis refashioned them into a political ideology of racial violence.

Anti-semitism in music is one of those stories that we think we already know all too well but that keeps revealing new and even more ugly chapters as time and scholarship march on. Whereas the literary and political strands of Jew-hatred have received their fair due of historical attention, musical anti-Semitism remains a blind spot for many Western scholars and critics. There is a simple reason for this omission. We do not see prejudice because we do not wish to see it. We reflexively resist acknowledging how much great music comes from bad men. Even when we do confront the moral failings and petty biases of great composers, our instinct is to quarantine the music itself. For, of all the arts, music most retains its hallowed aura of transcendence. In the pure realm of abstract sound, we often imagine, particularities and prejudices fall away to reveal a universal human condition.

This attitude is not intrinsic to music. It is a historical legacy of the Enlightenment. In its own way, this belief in the moral autonomy of art was also the driving force in the story of Jews in classical music. From the French Revolution onward, no field of modern European culture proved more attractive to Jews than music. There are many facile historical explanations for the Jewish gravitation to music: the artistic profession’s openness to outsiders, the legacy of an internal European Jewish tradition of music-making, the absence of a sonic taboo akin to Jewish aniconism. But the most powerful historical argument is the simplest one. Music appealed to Jews precisely because of its link to Enlightenment universalism.

We can see that effect in nuce in the case of the Mendelssohn family. In the late eighteenth century, Moses Mendelssohn, the philosopher and father of the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, proposed a philosophy of Judaism that stressed its theological compatibility with European modernity. Against Kant’s less than enlightened view that Judaism was a religion of calcified legalism, Mendelssohn, an observant Jew, defended the rationality and the beauty of Jewish law. But at the same time he called on his fellow Jews to shed their odd folkways and their parochial cultural differences. Practicing what he preached, Mendelssohn diligently applied himself to piano lessons. He authored a treatise on the proper tunings for the modern keyboard. In his influential writings on the philosophy of aesthetics, he posited a classical ideal of music as a harmonious sphere of human unity beyond Christian and Jew.

In the next generation, Mendelssohn’s son Abraham and his future wife were fixtures at the Berlin music academy sponsored by her family, the wealthy Itzig clan. Abraham’s in-laws served as patrons of Mozart and C.P.E. Bach. When the rest of Europe cared little, his wife’s aunt rescued Johann Sebastian Bach’s manuscripts from oblivion. Abraham also believed in the Enlightenment promise of a new age in which differences between Christian and Jew would cease to matter. Convinced the moment had nearly arrived, he baptized his children and raised them as Kantian Christians. His son Felix grew from child prodigy to famed composer, crowned by Schiller as the Mozart of his age. Felix was hardly Jewish at all, at least not judged by the religious terms of his grandfather. But the grandson and the grandfather shared a Jewish faith in music’s rational beauty and civic virtue.

What began as an Enlightened cultural ideal grew by mid-century into a distinctive social pattern for European Jews. In 1844, three years before Felix Mendelssohn’s death, Benjamin Disraeli playfully noted the omnipresence of Jews in European musical life in his novel Coningsby:

Were I to enter into the history of the lords of melody, you would find it the annals of Hebrew genius. But at this moment even, musical Europe is ours. There is not a company of singers, not an orchestra in a single capital, that is not crowded with our children under the feigned names which they adopt to conciliate the dark aversion which your posterity will some day disclaim with shame and disgust. Almost every great composer, skilled musician, almost every voice that ravishes you with its transporting strains, springs from our tribes. The catalogue is too vast to enumerate; too illustrious to dwell for a moment on secondary names, however eminent. Enough for us that the three great creative minds to whose exquisite inventions all nations at this moment yield, Rossini, Meyerbeer, Mendelssohn, are of Hebrew race; and little do your men of fashion, your muscadins of Paris, and your dandies of London, as they thrill into raptures at the notes of a Pasta or a Grisi, little do they suspect that they are offering their homage “to the sweet singers of Israel!”

Disraeli’s proud Romantic tribute to Jewish genius contained more than a hint of hyperbole. (For starters, Rossini was not a Jew.) But for all of its sentimental talk of a “Hebrew race,” its cultural logic belonged firmly to the same Enlightenment ethos that inspired the Mendelssohn clan’s devotion to music. In the eyes of Disraeli, the Jewish musical triumph was a humorous rebuff to lingering Christian religious prejudices. The spectacle of Jewish musical talent testified to civilization’s progress. This humane achievement is precisely what Wagner took aim at, six years later, in his commentary on the oversized Jewish presence

in European music.

Wagner’s Das Judenthum in der Musik, or Jewishness in Music, appeared under the pseudonym K. Freigedenk (“Free Thought”) in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1850. The piece constituted a provocative intervention into a debate in the German musical press about allegations of Jewish liturgical sonorities in the works of composers such as Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn. Then, in 1869, at the height of his fame, Wagner republished his essay in revised form as a pamphlet under his own name.

Wagner did not invent the language of musical anti-Judaism. As Ruth HaCohen has recently shown in her groundbreaking book The Music Libel Against the Jews, Christian Europe long obsessed over the sounds of Jewish difference. Out of the depths of the medieval Christian imagination came an aural dichotomy between the polluting noise of the synagogue and the harmony of the Church. In the nineteenth century, Romanticism introduced a new secular context. Now the artist’s nationality became the reference point for the art’s meaning. The successful composer tapped his national language to express his people’s cultural Volksgeist. Wagner combined these newer ideas of art and nationhood with the older “music libel.” The result was a potent new anti-Semitic myth.

“The Jew speaks the language of every country in which he has lived from generation to generation, but he always speaks it as a foreigner,” writes Wagner. Jews are a pariah nation with no land or language of their own. Hebrew has become a linguistic fossil; Yiddish is no more than a mangled dialect of German. But as a separate race, Jews by definition cannot integrate into other national cultures. Instead every individual Jew is indelibly marked by a “Semitic” accent, manifested in the “peculiarities of Jewish speech and singing.” This aural difference can be detected even among “assimilated” Jewish composers and poets. Conversion makes no difference. Consequently, Jews may achieve artistic renown, but they can never transcend their parasitic essence. They are destined to be aliens, imitators, and commercializers of other people’s cultures. In Wagner’s estimation, “Jewish music” (or better “Judaized music”) consists only of a negative image of the music of others. Rather than becoming good Jewish Germans, they turned Germans into Jews. Or, in the words of Haas, “Jews had masterminded an insidious deceit of racial camouflage that would eventually undermine German identity and its innate moral character.”

There is no solution, Wagner writes ominously at the conclusion of his essay, save for the disappearance (untergang or “going-under”) of Jews from European society. Was he actively demanding Jewish physical extermination, or merely fantasizing about their timely exit from the historical stage via assimilation? The question remains open to debate. Haas himself does not expand on this issue. Wagner was the single greatest literary influence on Hitler, he tells us at one point. Yet elsewhere he quotes Cosima Wagner’s diaries to suggest a softening of her husband’s attitudes toward the end of his life. But the important point is that the Wagner-Hitler connection, whatever it is, is not the heart of the matter. A too narrow focus on Wagner’s personal beliefs has actually obscured our view of the larger destructive force of Wagnerian musical antisemitism. The fantasy of anti-Jewish violence did not have to be taken to its logical extreme for its destructive impact in the realm of culture to emerge decades before Hitler came to power. Rather than a link in a punctuated chain of formal anti-Semitic ideology, the Wagnerian myth morphed into a broad, diffuse ideological current enveloping all of European musical life.

To detect Wagner’s influence is not simply a matter of documenting evidence of prejudice, whether hidden or overt, within German musical thought. As Haas explains, the single most salient fact for understanding the special potency of Wagner’s ideas was the unique extra-musical burden of politics that was placed on music in German society. From the middle decades of the nineteenth century onward, music functioned simultaneously as the vehicle for two distinct communities: German-speaking Jews seeking cultural acceptance as Germans and ethnic Germans seeking political independence as a unified nation. The two dreams uneasily co-habitated in a single musical tributary of the German cultural imagination. Witness the fate of Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion after its revival by Felix Mendelssohn in 1829. The modern premiere of what was then a completely forgotten work ignited a huge interest in both Bach and art music in German society. For Mendelssohn, Bach’s music symbolized the rebirth of man. For Wagner, Bach’s music sounded the birth of the German nation.

Once attached to Wagner’s charismatic vision and capacious talents, the anti-Semitic myth quickly became an explosive force in German music. Jewish visibility no longer formed a subject for curious speculation. Instead, Jewishness became an ideological litmus test to be applied to all performers, composers, and even critics. This binary division of the world into Judaizers and non-Judaizers seized German musical aesthetics as a whole. For Wagner’s ideas coincided with the mid-nineteenth-century split of German music into two factions. The Old School (defined stylistically, not chronologically) centered on Brahms and his followers. Though by no means artistic conservatives, they favored a Mendelssohnian ideal of music as an autonomous realm of beauty. Their rivals in the New German School of Wagner and Liszt (who also authored an anti-Semitic tract of his own) argued for the ideal of nationalism. Music’s fate was to serve as a vessel for political ideas, cultural forms, and social functions. In this atmosphere of growing polarization, merely to contest this nationalist claim was to risk being accused of hiding Jewish blood—a fate that befell Brahms.

Lest we dismiss this sort of anecdote as antiquarian gossip, Haas adduces a number of poignant examples of just how far the Wagnerian slur burrowed into the psyche of German Jews. A case in point is the writer and aesthetician Eduard Hanslick. The most important critic of nineteenth-century European music, Hanslick was a formidable proponent of classicism against romanticism. Yet the fearless critic crumpled in the face of Wagner’s anti-Semitism. Accused of being a Jew in the 1869 edition of Jewishness in Music, Hanslick responded by mocking the claim as the “biggest lie” in Wagner’s “deranged” brochure. Twenty-five years later, in his memoirs, Haas tells us, Hanslick revisited the charge, dismissing it as an absurdity. “I would have felt myself flattered to be burned at the stake alongside the likes of Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn” by Wagner, he writes, but “my father and all of his ancestors . . . were the sons of staunch Catholic farmers. In addition, they came from an area where the only Jews they would have encountered would have been tinkers plying their trade door-to-door.” Left out of this lineage, Haas reveals, is a cardinal fact: Hanslick’s mother was herself Jewish by birth. Evidently, decades after the original attack, the wound had not healed. The game of racial contortions continued.

“With Wagner or against him, but not outside him,” wrote theearly-twentieth-century Russian music critic Sergei Durylin. Today it is hard to overestimate just how large Wagner’s shadow loomed in the decades after his death. It was not just the popularity of his operas. From roughly the 1880s through World War II, Wagnernian anti-Semitism seeped into every corner of European music, both popular and classical. It could be found just as commonly in Paris or Moscow as in Vienna.

Wagnerian ideology played its greatest trick on composers of Jewish origin. For it presented a paradox. Since the Jews had no authentic culture of their own, Jewish music by definition did not exist. But by their very racial nature, Jews could not help but sound Jewish in any music they authored. In the face of this dilemma, how was one to respond? One way to read the modernist turn of Mahler and Schoenberg is as an attempt to escape this trap by dissolving conventional tonality—and with it Jewishness—in a pool of dissonance. Where hints of folklore surface in Mahler’s music, as in the First Symphony, they arrive distorted beyond recognition into a modernist grotesque. Thus Mahler’s melodic sources avoid easy categorization as “Bohemian” or “Jewish.” Schoenberg famously claimed the achievement of the “emancipation of dissonance” in his music, but it is not a stretch to see another kind of emancipation hovering in the background.

But of course there was no single Jewish pathway into modern music. One of the great virtues of Haas’s book is his careful attention to the full range of aesthetic choices made by early-twentieth-century German and Austrian Jewish composers. For every Mahler and Schoenberg, he reminds us, there was a Hans Gál or an Egon Wellesz, talented neo-classicists who leapt backward over Wagner in pursuit of Mendelssohnian purity. The great Alexander Zemlinsky eschewed atonality for a temperate modernism that looked forward harmonically without completely letting go of the nineteenth century. Still others, such as Erich Wolfgang Korngold, rejected all hint of the avant-garde in search of a neo-Brahmsian rapture. Like so many of those exiles fortunate to escape to Hollywood, he took his gift for theatrical composition into a successful career in Hollywood, where he virtually created the modern film score. Late Romanticism lived on as well in the works of major composers such as Erich Zeisl and Walter Braunfels. The latter, raised a Protestant, a convert to Catholicism, was branded half-Jewish in the Nazi campaign against Entartete Musik, or “decadent music.” In the early 1940s, while in internal exile, he composed a stunning set of string chamber works, often compared to Beethoven’s late quartets, that offered a damning capstone to the German Romantic tradition.

Although Haas barely touches on it, the most original Jewish musical responses to Wagner came from those composers outside Germandom. Further east and west in pre–World War I Europe, a cohort of composers attempted to refute Wagner directly. Flipping his theory on its head, they argued that precisely the Ashkenazi musical accents that Wagner had ridiculed as “the sound of Goethe being recited in Yiddish” could be the kernels of a new Jewish national music. Composers such as Ernest Bloch and Darius Milhaud in France and Mikhail Gnesin, Moyshe Milner, and Alexander Krein in Russia danced a complex dance with fictive twin shadows, embracing the clichés of Jewish Orientalism—ornament, melisma, lyricism—but transvaluing them into positive emblems of national identity. Instead of “Judaized music,” they sought their own Jewish variations on tonal modernism. The result was an entire Jewish national school of composers that flourished in the 1920s and 1930s across the Soviet Union and Central Europe. Russian Jewish folklorism also left its lasting musical mark in the mid-century oeuvres of Dmitri Shostakovich and his forgotten Jewish musical partner, Mieczysław Weinberg, the last great composer to emerge from behind the Iron Curtain. The Hebrew and Yiddish operas, symphonies, and chamber music now emerging from the archives promise a reevaluation of Jewish musical history as a whole.

Haas extends his formidable survey through the war, tracing the divergent fates of composers as they sought refuge across the world. After the war, even those who survived would find no triumphant homecoming. Haas concludes by recounting an episode from the life of the composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Having spent the war years in exile in Los Angeles, he returned afterward to visit his beloved native Vienna. There, a former neighbor recognized him. She blurted out: “Jesus, Mary and Joseph! Professor Korngold! I don’t believe my eyes! You’re in Vienna!—When are you going back home?” The disowning of Korngold was not just a bitter epitaph to a career interrupted by the Nazis. It was emblematic of the larger underappreciated drama. Haas’s title suggests a specific moment when the Holocaust stripped classical music of its Jewish voices, but his evidence proves that the purge had been happening all along. The Nazis invented a new kind of political terror, but the racial script that the public followed had been written long before.

Since the anti-Jewish musical myth well preceded the Holocaust, it easily withstood the destruction of the Nazi Reich. In many ways, it remains with us today. This is not simply a matter of Wagner’s hate literature resurfacing on the streets of Europe. It is also a question of the appalling ignorance of Jewish musical history in European and American conservatories and universities. (The same, unfortunately, might be said for the one place where an acute awareness of Wagner’s legacy lives on: Israel.) More disturbingly, the myth lingers in how we actually listen to our own collective musical past. Thanks to the labors of Haas and others, we know a great deal today about the musical voices that vanished with the Nazi genocide. But, ironically, the more we learn of banned composers, the harder it is to hear their music outside the framework of the Holocaust. The ending we all know and cannot forget reverberates backward. This is regrettable. For when the composer’s music is permanently coupled to his victimhood, Jewishness becomes merely a negative condition. That generation upon generation of Jewish musicians confronted racism at the heart of classical music does not mean that every work they wrote must be heard as a Semitic cry of despair. Not every knock at the door means the secret police. Not every minor-key passage is lachrymose. Still, the sonic shadows prove hard to elude. We may think we inhabit a post-Holocaust soundscape, but we still very much live in Wagner’s world.