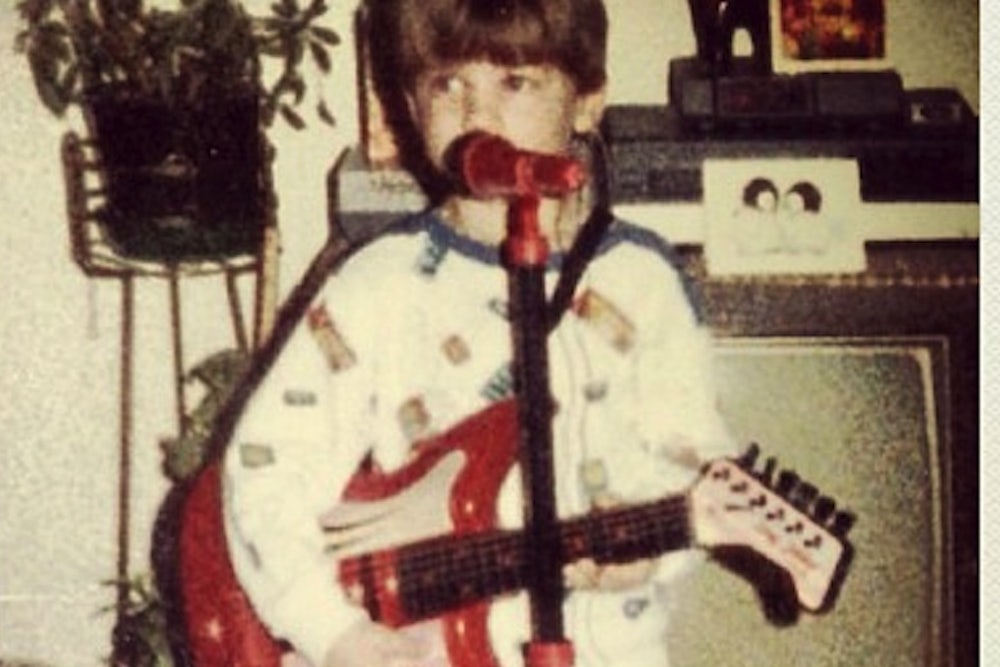

If your Facebook feed is looking a little antique these days, you probably have #ThrowbackThursday (#TBT) to thank. The hashtag-inspired trend has people posting snapshots from their youth—romantically faded at the edges or washed with a nice sepia-tinted filter—along with captions like “best sister ever!”

But the trend is not just the latest iteration of sentimentality plus narcissism. A new study by University of Portsmouth sociologist Laura Hyman shows that happiness possesses a strong temporal dimension, and reflections on the past can be a significant source of happiness for us in the present. Older generations are especially likely to view the past—both the collective social past and their personal past—as happier than the here-and-now. But younger people idealize the past too: Though they don’t perceive it as necessarily superior to the present, they understand memories as a special source of pleasure. In fact, the association between memory and happiness is so strong that researchers call the act of reminiscing a “technique” people use in order to make themselves feel better. Sometimes memories engulf us unexpectedly, but we can also choose to reminisce in order to induce warm, fuzzy feelings.

The study drew on interviews with 26 anonymous adults in the United Kingdom—ranging from ages 22 to 80—who were asked about their ideas and perceptions of happiness. Subjects weren’t probed specifically about memories, but most recounted memorable past events or reflected on the past in their narratives of happiness. Of course, memories aren’t stable, fixed, or even accurate constructs. The picture you post for this week’s #TBT might disclose a completely different set of emotions and associations when you view it again a year from now.

Does the pleasure of remembering the past trump the enjoyment of being in the present? Our tendency to interrupt the moment in order to put it on Instagram suggests as much. Ironically, documenting every moment might actually cause us to lose the very memories we long to immortalize. Fairfield University psychologist Linda Henkel tested this hypothesis on college students. On a museum tour, she asked the students to photograph 15 works of art and to simply look at 15 others. When tested on the artworks the following day, the students remembered fewer of the ones they had photographed than the ones they had only viewed. Their memories of the photographed art were less detailed, too.

The issue isn’t just that taking a picture cuts into the time we otherwise have to view or experience a moment. The camera also intrudes on direct experience: Instead of enjoying the thing we seek to document, Henkel suggests, we’re occupied with our camera. In our anxiety to record experience, Henkel says, we risk diminishing its vividness in our own psyche.

Henkel’s data is new, but it picks up on something Plato noted: Recording—in the form of writing—would lead people to remember not “within themselves,” but through external stimulants. “What you have discovered,” Socrates advises Phaedrus, “is not a prescription for memory, but for being reminded.”