More Americans came into contact with maps during World War II than in any previous moment in American history. From the elaborate and innovative inserts in the National Geographic to the schematic and tactical pictures in newspapers, maps were everywhere. On September 1, 1939, the Nazis invaded Poland, and by the end of the day a map of Europe could not be bought anywhere in the United States. In fact, Rand McNally reported selling more maps and atlases of the European theaters in the first two weeks of September than in all the years since the armistice of 1918. Two years later, the attack on Pearl Harbor again sparked a demand for maps. Two of the largest commercial mapmakers reported their largest sales to date in 1941, and by early 1942 Newsweek had named Washington, D.C. "a city of maps," one where "it is now considered a faux pas to be caught without your Pacific arena."

War has perennially driven interest in geography, but World War II was different. The urgency of the war, coupled with the advent of aviation, fueled the demand not just for more but different maps, particularly ones that could explain why President Roosevelt was stationing troops in Iceland, or sending fleets to the Indian Ocean. Americans had been reared on the Mercator map of the world, a sixteenth-century projection designed for navigation but which created immense distortions at the far northern and southern latitudes.

Indeed, Americans had become so used to seeing the world mapped on the Mercator projection that any other method met with resistance, both in classrooms and living rooms. But as aviation displaced sea navigation in the twentieth century, Americans were sorely in need of maps that conveyed the new realities of distance and direction in the air age.

The most important innovator to step into this breach was actually not a cartographer at all, but an artist. Beginning in the late 1930s, Richard Edes Harrison drew a series of elegant and gripping images of a world at war, and in the process persuaded the public that aviation and war really had fundamentally disrupted the nature of geography.

Harrison came to maps by chance. Trained in design, he arrived in New York during the Depression and made a living by creating everything from whiskey bottles to ashtrays. One day, a friend at Time asked him to fill in for an absent mapmaker at its sister publication, Fortune. That unexpected call led to a lasting collaboration, one where Harrison used techniques of perspective and color to translate the round earth onto flat paper. In fact, Harrison considered his lack of training in cartography an advantage, for he had no fixed understandings of what a map should look like.

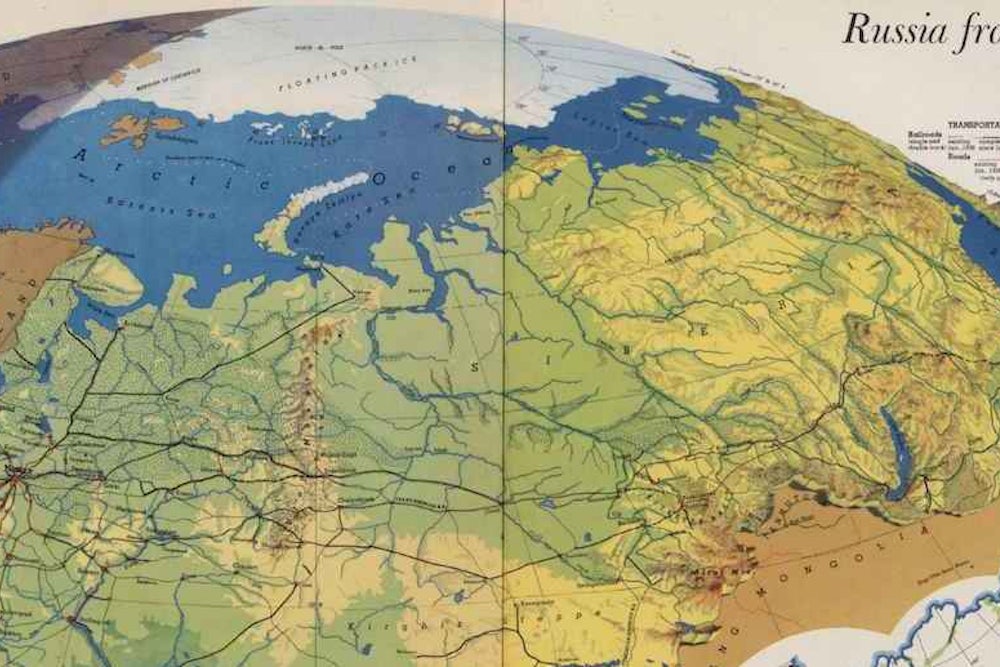

Throughout the war, Harrison dazzled readers of Fortune with artistic geo-visualizations of the political crises in Europe and Asia. The key decision he made was to reject the Mercator projection, which had outlived its purpose. Instead, he drew on other projections, such as this one from 1943, centered on the north pole and which drew Eurasia and North America together, though distorting the southern hemisphere as a result.

In the original version of the map, from August 1941, Harrison blackened the entire Soviet Union as part of the Axis to reflect the recent German invasion. In the edition two years later here, the Soviets have aligned with the Allies, and the threat of the Axis appears more limited. But in either edition it was impossible to ignore the prospect of American stewardship that gradually—but completely—displaced the isolation of the 1930s. For Harrison, the polar projection was the new geographic reality, one that necessitated American internationalism.

Harrison's most notable legacy was a series of colorful and sometimes disorienting pictures (not quite maps) that emphasized relationships between cities, nations, and continents at the heart of the war. These maps were published in Fortune, then issued in an atlas that became an instant bestseller in 1944.

The most powerful of these images anticipated the perspective of Google Earth. Here Harrison reintroduced a spherical dimension to the map, focusing on the theaters of war in a way that—for instance—rendered the central place of the Mediterranean and the topographical obstacles facing any invasion of southern Europe. National borders were secondary to regional configurations, and the viewer was forced to reckon strategically with the complex terrain.

Harrison's ability to play with scale evokes the perspective of a pilot, but one placed at an infinite distance. Cartographers were quick to point out that no such perspective existed in nature, yet by drawing the topography with such care Harrison made the terrain far more real than it had been in the abstract representation of mountains used on traditional maps. His map of Russia from the south, created just before the end of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, powerfully illustrates the sheer size of the Soviet Union and its population. Notice his use of light and shadow to depict the multiple time zones encompassed by the Russian landmass, while the graphic at the lower right captured the massive growth of the urban population in the western regions.

With his imaginative use of color, Harrison generated spatial depth in a way that gave the public a vivid picture of places that otherwise remained foreign, such as this close up detail of his map of Japan from Siberia.

The public welcomed Harrison's images: The first edition of his atlas sold out before it even hit the shelves, and throughout the war he was inundated with requests for maps drawn with his signature techniques. Most professional cartographers celebrated his provocative style for its ability to foster a more dynamic understanding of geographical relationships, and the military hired Harrison to make maps for soldiers in the field and to help train pilots to understand regions that had yet to be photographed from the air. It was not long before Time, Newsweek, and the wire services began to experiment with new visual mapping techniques popularized by Harrison. The cartographic logjam had been broken, for Harrison's views struck a chord with a public hungry for information.

By 1944, Harrison had become a minor celebrity for his elegant pictures of global crisis, ones that could be intuitively understood by readers of widely varied levels of literacy and sophistication. His startling views of Japan from Alaska and the Solomon Islands brought home the proximity of the Axis and prepared the public for a dogged fight in the Pacific. Such a view was entirely absent from traditional maps of the north Pacific, which comfortably distanced Japan and Asia from North America across a massive ocean.

Harrison's critics claimed his work was more propagandistic and pictorial than scientific and reliable, governed by caricatures of the globe rather than fidelity to latitude and longitude. Fair enough. But his goal was to wrench Americans out of a two-dimensional sense of geography, and embrace an understanding of perspective and direction. In the process he reintroduced a sense of artistry and drama that directly affected the look and feel of popular maps.

When I interviewed Harrison in New York at the end of his life in 1993, he still insisted that I call him an artist rather than a cartographer, for he disdained the constricted techniques of mapmakers who were hidebound by convention. In fact his images sit somewhere between art and cartography, supplying the missing link between the globe and the map. The term "global" has become a cliché in the early twenty-first century, but in Harrison's case it's an appropriate characterization. In redrawing the map of the world, Harrison contributed to a reconsideration of America's role in that world.