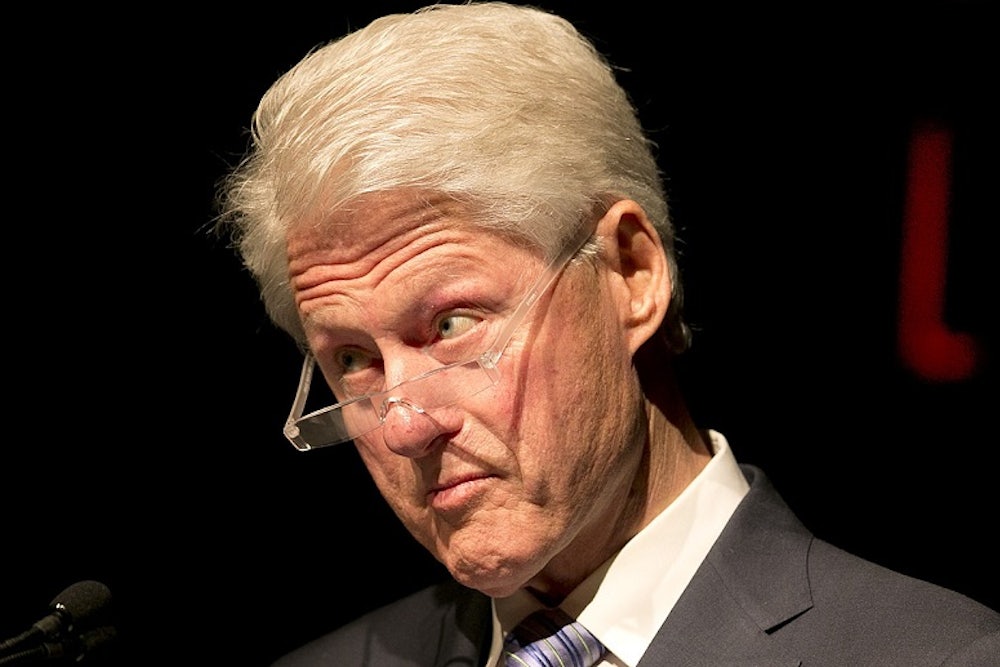

Bill Clinton is always one to make a deal. Speaking at the Peterson Foundation Fiscal Summit on Wednesday, the former president proposed a way to rebuild America’s aging infrastructure while giving corporations a huge tax cut—a plan that may have what it takes to cut through Congress' partisan gridlock.

President Barack Obama has repeatedly called for more infrastructure spending during his time in office. His most recent plan, as part of his 2015 federal budget, would spend $302 billion on infrastructure over the next four years. Given the historically low interest rates at which the U.S. can borrow and the growing need for infrastructure investment, it would make sense to fund the proposal with debt. But Obama keeps his plan deficit-neutral by closing corporate tax breaks anyways.

Due to Republican opposition, Obama’s plan is dead on arrival in the House. But Clinton's idea is supported by politicians on both sides of the aisle. He would grant U.S. multinational corporations a repatriation tax holiday as long as they bought infrastructure bonds with 10 percent of the repatriated funds. In other words, U.S. companies would get a big tax break as long as they helped seed an infrastructure bank. Representative John Delaney and senators Michael Bennet and Roy Blunt have introduced similar proposals in the House and Senate.

"I believe if we repatriated the money now on terms that required say, 10 percent, of it to go into an infrastructure bank with a guaranteed rate of return, tax-exempt, of X, as a first step towards corporate tax reform, you could get a lot of that money back in America, turn it over, increase economic growth and launch the infrastructure bank with an adequate level of capital," Clinton said.

U.S. multinational firms are currently sitting on more than $2 trillion in foreign profits because they are confident that they can avoid paying the full 35 percent corporate tax rate: A “one-time” repatriation tax holiday granted by President George W. Bush in 2004 has convinced them to hold out for another one. In 2004, multinationals could bring back up to $500 million with a one-time tax exemption of 85 percent—lowering the effective tax rate to 5.25 percent. Under the agreement, companies were required to invest the funds domestically to spur economic growth. But money is fungible—multiple studies have found that firms did not use the money for those purposes.

“The evidence shows that firms mostly used the repatriated earnings not to invest in U.S. jobs or growth but for purposes that Congress sought to prohibit, such as repurchasing their own stock and paying bigger dividends to their shareholders,” economists Chuck Marr and Brian Highsmith wrote about the 2004 repatriation holiday. “Moreover, many firms actually laid off large numbers of U.S. workers even as they reaped multi-billion-dollar benefits from the tax holiday and passed them on to shareholders.”

Even worse, the 2004 holiday set a precedent. Now, multinationals are even more committed to holding funds overseas, expecting that they will eventually receive yet another holiday. Another tax repatriation holiday would only provide multinationals further incentive to keep the money overseas, which would further decrease government revenues. In 2011, the Joint Committee on Taxation calculated that a repatriation tax holiday similar to Bush’s would decrease revenues by $79 billion over a decade. Clinton’s plan differs from Bush’s, but the principle that drives lower revenues—multinationals keeping future profits overseas—is the same.

Then, as Jared Bernstein has written, there is the basic question of fairness. Multinational corporations, holding out for a tax break, have withheld trillions of dollars in profits that could have boosted the economy over the past six years. Domestic producers have not had that luxury. Multinationals are simply reacting to incentives created by Bush, but now it's time to show them that the 2004 holiday was a one-time-only offer.