Vera Nabokov, as far as I know, has not yet been transformed into the heroine of a novel. But it's only a matter of time. The demand for fiction cast in the template of “the creative person's wife” shows little sign of abating.

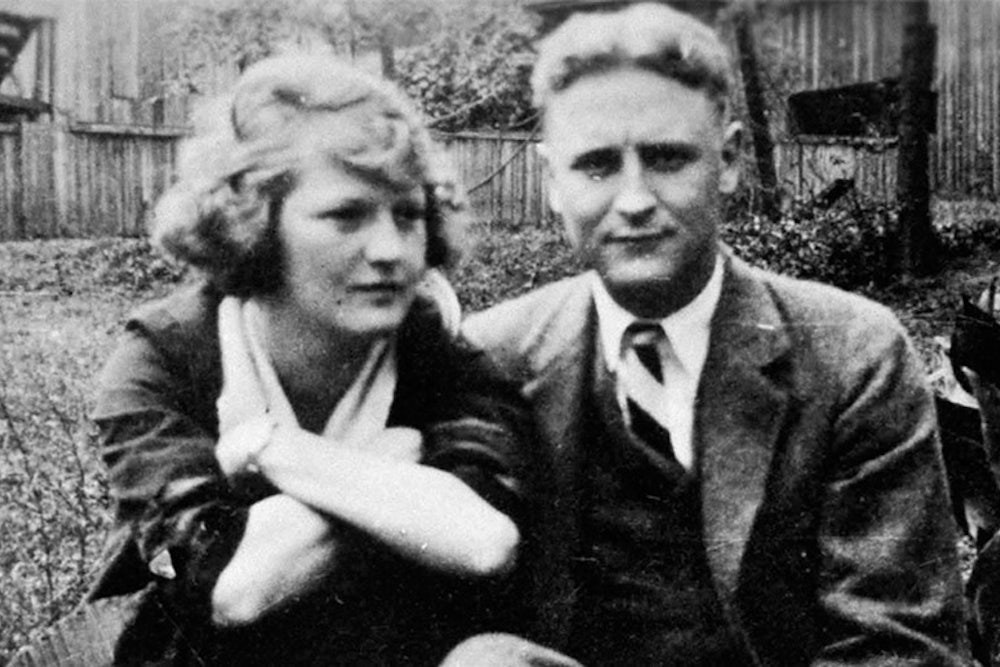

Zelda Fitzgerald alone inspired several books last year: There’s Ann Fowler's Z (in which Zelda narrates her story from the asylum), Erika Robuck's Call Me Zelda (in which an asylum nurse’s narrates her story), and R. Clifton Spargo's Beautiful Fools (the tale of Zelda and Scott, briefly reunited in middle age). The marital habits of Fitzgerald's friend-turned-rival Ernest Hemingway provided fodder for The Paris Wife; all four spouses get their due in Mrs. Hemingway, a British hit to be published in the U.S. in July. Robuck, who seems to be making a career of fictionalizing the lives of writers, also examined Hemingway through his Key West maid in Hemingway's Girl. This month, we saw Dark Aemilia: A Novel of Shakespeare's Dark Lady; next month, Freud's Mistress is out in paperback. (The genre extends beyond writers: T.C. Boyle's The Women, has Frank Lloyd Wright’s wives and lovers as its focus; Loving Frank, Nancy Horan's bestseller, is about Wright's mistress, Memeh Cherry.)

What explains the proliferation of these novels? Part of the appeal lies in the fantasy of glamour behind the drudgery of writing. Told from the perspectives of wives and lovers, and freed from the need to adhere strictly to biographical specifics, these novels have the liberty to linger on the sexier aspects of their subjects’ lives. Less study, more bedroom. Fictionalized accounts also offer a sense of intimacy: what better way to get inside the heads of literature’s greatest minds than through their assistant-amanuensis-lover-housekeeper-cook-secretary? Vera Nabokov, as Koa Beck discussed in a recent essay for The Atlantic, was all of these things to her husband. It seems only a matter of time.

Though it bears the name of a now-famous literary giant, Susan Scarf Merrell's new novel, Shirley, is part of this spate of novels that examine the constellation surrounding famous men. Based on the life of Shirley Jackson—author of the short story “The Lottery” and We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and a number of masterpieces in an eerie, minor key—the novel chronicles Jackson’s life with her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman. Hyman was a famous literary critic in his day—inspiring acolytes among his peers and students at Bennington College, where he taught for much of his adult life. It was Hyman, rather than Jackson, who was considered the intellectual of the couple during their lifetimes. It was Jackson, however, who paid the bills, with her stories and novels, while also taking care of her children.

Because of this dynamic, Shirley has the potential to be an interesting addition to the genre—not just an examination of what it means to stand beside a Great Man, but to stand beside a Great Man, knowing, or at least suspecting, that you might be greater. Hyman's work is now all but forgotten. Jackson's stature has grown. All of her novels have recently been re-issued, as has a forthcoming collection of newly discovered stories; a biography by Ruth Franklin is scheduled to be published in 2016. Jackson's writing, with its themes of surveillance and anxiety, feels more relevant than ever. More than 65 years later, people still argue about “The Lottery,” Jackson's most famous and controversial story. (One of the story's original detractors, Miriam Fried, now 98, stood by her original critical letter to the New Yorker, saying it was “such a harsh story.”)

Unfortunately, Shirley is the book equivalent of looking an adversary in the eye only to scurry away. This is especially bizarre in light of Merrell's professed admiration for Jackson and her work. To be fair, Merrell’s project is a tougher ticket than much of the similar work that’s come before. It would make little sense for the novel to unfold in the form of a melodramatic trifle (like the Fitzgerald and Hemingway novels), because such a style would be at odds with Jackson’s work. It cannot be an overarching examination of Great American Archetype because Jackson worked in the shadows, teasing out the terror of the underside of the domestic. As such there are two egos and legacies to contend with.

Even so, the novel has some fairly fundamental flaws. Merrell decides to emulate rather than mimic Jackson's sensibility in the form of a fictional character named Rose Nemser, the pregnant, teenage wife of a Bennington graduate student. Rose’s husband Fred works closely with Hyman, and the couple lives in the Jackson-Hyman house. This point-of-view disturbs, but for the wrong reasons. We have pages and pages in Rose's head, which is not a particularly exciting place to be—if she were clever and unlikeable, at least she might be interesting. Rose's “writing”—in “lowercase, no capitals, just as Shirley does”—is even more awkward than her consciousness. Bernard Malamud and his wife appear in a bizarre dinnertime cameo—an appearance that is, purportedly, intended to demonstrate the Hyman’s active literary life, but that comes off more like an episode of fan fiction.

Shirley suffers from two additional sins connected to its uneasy relationship with its real-life inspiration. It puts dialogue in the mouths of two of Jackson's children, both of whom are very much alive—and fiercely protective of their mother's legacy. Merrell had no legal requirement to obtain the permission of Jackson’s children, of course, but the ethics are still squirrelly enough to distract from the work. The second problem is the plot, which tries to forge a malevolent connection between Jackson and the still-unsolved 1946 disappearance of Bennington student Paula Jean Welden. The disappearance of this student was the supposed inspiration for Jackson's 1950 novel Hangsaman. Penguin's recent reissue references this inspiration, but Franklin, Jackson's biographer, refutes the connection. The ethics of this adaptation are dubious, not just because it feels cheap to forge a link between Jackson and Welden for which no evidence exists, but because doing so detracts from the genuine mystery, and likely tragic outcome, of Welden's vanishing.

Largely, Shirley fails because it can't decide what kind of book it should be. Its titular character seems more like Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? than a three-dimensional human being. Stanley Hyman is little more than a sad caricature, falling into easy stereotypes of the intellectual philanderer. Any possibility that Rose poses—to probe the dynamics of proximity to a great man, the sacrifices a woman with a family makes, and the way those sacrifices can be heightened in intellectual environments—remains unfulfilled. Rose simpers and gets overwhelmed by young motherhood, but so what? She's no different than countless other young wives yet to be emboldened by feminism, and the proximity to Jackson and Hyman can't make Rose dynamic. A climactic scene where the spousal roles shift, which is intended to show Rose in a bold light, is instead a bad parody of a melodramatic film.

The appeal of these spousal tales is in their attempted elevation of the writer's life to the same level of their art, and in the idea that the day-in, day-out toil of writing is part of a larger, more significant narrative arc. In the hands of capable practitioners, these fictionalizations of a writer’s orbit clue readers in to struggles that play out in the authors’ work. The less capable turn emotional depth into tone-deaf soap opera. Should that hypothetical Vera Nabokov novel come across my desk, I know what camp I'd want it to belong to. But I also know where it would probably end up.

Image via Shutterstock.