"The Demigod"

May 22, 2006

"You lament the monotony of ass," Flaubert wrote to his young disciple Guy de Maupassant in 1878, two years before the master's death of a heart attack at age fifty-eight. "There's a simple remedy for that—don't avail yourself of it." Maupassant had complained that he was as bored with women's asses as he was with men's minds. "Too many whores!" Flaubert admonished him. "Too much canoeing! Too much exercise! Yes, sir! The civilized man doesn't need as much locomotion as physicians pretend." Flaubert, himself a physician's son, offered a more oblique remedy for the second affliction of which Maupassant complained. The tedium of men's minds was one of Flaubert's great topics; early and late, from Madame Bovary to Bouvard and Pecuchet, he avidly collected specimens of human stupidity. What is his Dictionary of Received Ideas if not a compendium of mental monotony, each cliché arrayed like an impaled butterfly for close examination? From Jacques Barzun's translation: "ACCIDENT. Always 'regrettable' or 'unlucky'—as if a mishap might sometimes be a cause of rejoicing." "FULMINATE: Nice verb." "HYPOTHESIS. Often 'rash,' always 'bold.'" The only escape from cliche, Flaubert insisted, was tireless pursuit of the right word. "I am often hours chasing a word," he told one hasty writer. "For turns of phrase," he assured Maupassant, "search and you will find."

In his splendid new biography, Frederick Brown, the author of well-received lives of Zola and Cocteau, deftly dismantles the most durable cliche concerning Flaubert himself. The difficult task that Brown has set himself, nowhere stated but everywhere pursued in this vigorously researched, intellectually nuanced, and exquisitely written book, is to challenge the long-standing view that Flaubert started out as a Romantic writer in the vein of Chateaubriand or Lamartine, underwent a violent "purge" at the insistence of two wise friends, and was miraculously transformed into a Realist with the writing of Madame Bovary. Francis Steegmuller's influential and recently reprinted Flaubert and Madame Bovary is structured according to this conceit; its three sections are titled "Romanticism," "The Purge," and "Realism." The old Penguin translations by Robert Baldick carry a succinct version of the myth: "In his early works …Flaubert tended to give free rein to his flamboyant imagination, but on the advice of his friends he later disciplined his romantic exuberance in an attempt to achieve total objectivity and a harmonious prose style."

The legend of the purge fed the self-importance of its inventors, those same friends—the poet-librarian Louis Bouilhet and the photographer-journalist Maxime Du Camp—who were eager to enlist Flaubert in their own nascent creed of Realism, a label that Flaubert always resisted. According to Du Camp, they solemnly gathered in September 1849 as Flaubert read aloud (or rather, "sang and chanted the phrases") from the first version of The Temptation of Saint Anthony, his dream vision of a fourth-century ascetic prey to the successive illusions of humanity. They waited for the plot to begin; they waited in vain. "There was no progression—the scene always remained the same." After four days of reading, eight hours a day, Flaubert asked for their verdict. "We think you should throw it into the fire," said Bouilhet, "and never speak of it again." They insisted that Flaubert adopt a more "down-to-earth subject, one of those incidents in which bourgeois life abounds"—say, adultery among the provincial bourgeois. To their relief, Flaubert became an updated Balzac, the dry-eyed chronicler of modern mores whom we meet in such masterpieces as Madame Bovary, Sentimental Education, and "A Simple Heart."

The only problem with this account is that it doesn't stand up to scrutiny. Flaubert followed Madame Bovary with Salammbi, his jeweled fantasy of the Orient (that is, the Middle East), and paired "A Simple Heart" with "Herodias," his hothouse fantasy of the story of Salome's mother and John the Baptist. Far from burning The Temptation of Saint Anthony, Flaubert, "a hoarder rather than an arsonist," continued to work intermittently on his "revenant," as Brown calls it, until it was published, in its third version, in 1874. Reviled by reviewers, the hallucinatory prose-poem was admired by Baudelaire for its "undercurrent of rebellious suffering … the dark thread that guides one through this pandemoniacal glory-hole of solitude," and by the young Freud, and found its true audience in the fin de-siècle Symbolist generation of Huysmans and Redon.

It is a guiding insight of Brown's lucid account of Flaubert's writing that it did not so much progress as intensify and crystallize. Like an architect with a master plan, Flaubert's program seems to have been set early on. A draft of Sentimental Education (with an episode set in New York) was complete by 1845, twenty-five years before the publication of the final version, which is itself concerned with immobility and drift. The novel's hero, Frederic Moreau, is "motionless" when we first encounter him on board a riverboat on the Seine; and after viewing the political turmoil of 1848 (as Flaubert did) without enthusiasm, and wandering aimlessly in pursuit of a married woman, he is motionless at the end, fondly remembering a brothel he was afraid to visit in his youth. Kafka, whose copy of this novel was, as Brown notes, his "constant companion," compared the ending to Moses's failure to enter Canaan. Static tales of ascetic saints—first Saint Anthony and then the exquisite "Saint Julien l'Hopitalier," inspired by a stained-glass window in the Rouen Cathedral—remained at the center of Flaubert's imaginative universe. There was no progression. The scene always remained the same.

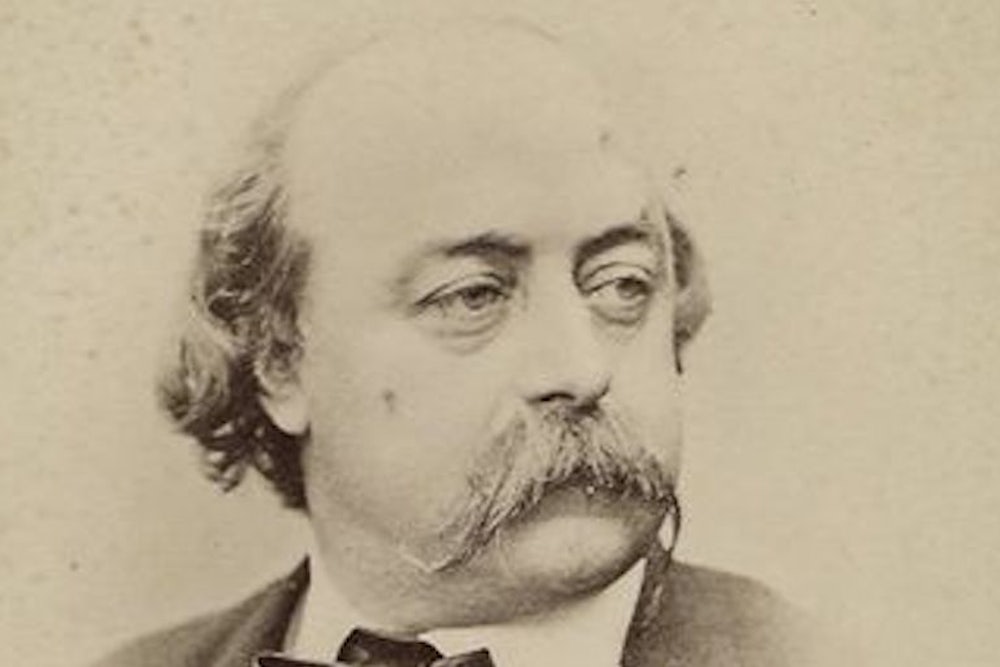

Brown's biography begins and ends in Rouen, the foul-smelling industrial city on the Seine between Paris and the English Channel, where Flaubert was born in December 1821. Rouen was the industrial hub of Normandy, where ships discharged bales of American cotton for the looms of the "Manchester of France," as an English guidebook dubbed the city. For all his exotic travels in the Middle East, and his fantasies to flee to America or China, to serve as a diplomat in Rome or Constantinople, Flaubert was first and last a Norman. According to Brown, Normandy "was the landscape of his youth and of all his seasons. It was the taste in his mouth and the verdant prison where he dreamed of deserts." Flaubert's father was the leading surgeon in the city; his mother came from a distinguished Norman family. It was assumed that Gustave would train for one of the professions, medicine or law, and take his place in the respectable bourgeois order of the city.

Two things derailed this plan. One was Flaubert's genius—the sheer power of his shaping imagination—and the superb classical training that he received in the strict Rouen schools. Of his remarkable high school teachers, Brown singles out the historian Adolphe Cheruel, a native Rouennais who had studied under the great Michelet, Romantic chronicler of witches, the sea, and the Rouen martyr Joan of Arc. At the very beginning of his career—he would later occupy a chair at the Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris—Cheruel inspired his students to consult primary documents as they surveyed all of Western civilization, and he introduced them to the revolutionary ideas of Vico and Herder. Brown is right to suggest that Flaubert might well have become a historian under this inspiriting regime, like the great historian of ancient cities Fustel de Coulanges, who studied under Chéruel at the Ecole Normale Superieure. It is the depth of Flaubert's learning that partially accounts for the aggrieved tone in Edward Said's pages in Orientalism (a work that Brown pointedly ignores) devoted to Flaubert's sexual tourism in the Middle East—where, as Brown notes, "no whorehouse between Cairo and Nubia was so low" that Flaubert and Du Camp "wouldn't stoop to enter it." How could Flaubert, Said wondered, who "came to the Orient prepared for it by voluminous reading in the classics, modern literature, and academic Orientalism," conclude that "the oriental woman is no more than a machine: she makes no distinction between one man and another man"?

The stories that the precocious Flaubert began writing in his teens derive from his forays into history. An early tale of the plague in Florence concludes with this impressive sentence: "In every man's life there are pains and sorrows so keen, mortifications so poignant, that for the pleasure of insulting his tormentor he will abandon and contemptuously discard his masculine dignity like a theater mask." For every piece of writing thereafter, Flaubert pursued detailed research in primary documents and secondary sources. In this sense, all his novels were historical novels, even those set in the recent past. No research was necessary for the Romantic clichés that stuffed Emma Bovary's imagination: "She wished she could have lived in some old manor house, like those chatelaines in low-waisted bodices under their trefoiled Gothic arches, spending their days, elbows on the parapet and chin in hand, peering across the fields for the white-plumed rider galloping toward her on his black steed." Instead she marries a country doctor, whose botched operation on a stableboy's clubfoot—an excruciating chapter fully researched by Flaubert—confirms her sense of his mediocrity. Flaubert attended an agricultural fair, notebook in hand, to get the details right in the famous scene that crosscuts a provincial official's spiel about the virtues of "tillers of the soil" and fertilizer with the rake Rodolphe's seduction of Emma in an upstairs room nearby. "It makes for a brilliant counterpoint," Brown notes, "as both councilor and seducer recite canned ideas, each to a gullible audience."

The other decisive factor in Flaubert's choice of career was epilepsy, the seizure disorder that plagued him from his early adulthood until his death. Brown dates the onset of Flaubert's seizures to New Year's Day in 1844, when Flaubert and his brother were riding south at night after a visit to the seaside resort of Deauville. Flaubert, holding the reins, suddenly fell unconscious. Upon regaining consciousness, his memory was washed clean of everything except a sensation of being swept off in a "torrent of flames." He promptly abandoned his legal studies. While his haughty and retrograde brother succeeded their father as Rouen's chief medical official, Gustave retreated to the rural family compound at Croisset, on the Seine outside Rouen, to pursue his scholarly and literary interests and, according to his new mantra, to "live like a bourgeois but think like a demigod." Meanwhile he underwent medical treatment—or rather torture. Brown devotes some hair-raising passages to what doctors resorted to as remedies for a disease they associated with sexual dysfunction; Flaubert endured mercury rubs, leeches applied behind his ears, "syringes thrust up his rectum," and incisions in his neck held open by a tightened "subcutaneous leash" to allow the malign "humors" to escape.

Two years later, in 1846, he experienced a double blow, with his father's death in January and the death of his beloved sister, Caroline, in March. Flaubert assumed the role of head of the household in Croisset, watching over his widowed mother and assuming the care of his niece, also named Caroline. Brown charmingly relates how Flaubert threw himself into Caroline's education: "Geography lessons were held in the garden, where, equipped with a bucket of water and a shovel, he dug up soil to model islands, peninsulas, gulfs, promontories." Caroline later wrote of visiting him in his writing retreat, furnished with a white bearskin and a gilded Buddha. He regaled her with "gobbets of Plutarch" and seemed genuinely puzzled when she asked him if Alexander and Alcibiades were good or not. "Good?" he asked. "Well, they certainly weren't accommodating gentlemen. What difference does it make anyway?"

A kindred exasperation runs through his famous correspondence with Louise Colet, the "beautiful, tall, full-bosomed" and well-known poet eleven years his senior, whom he met in a fashionable sculptor's studio in Paris during the summer of 1846, and with whom he began a bumpy affair that lasted until 1854. Their first attempt at sex, in a hotel, was a failure. They were more successful in a horse-drawn cab, perhaps because, as Brown dryly remarks, "Louise may have seemed less daunting, because more sluttish, in a cab than in bed." In any case, Flaubert was most affectionate when absent. Like Kafka (to whom Brown compares him) and Emily Dickinson, Flaubert found the epistolary distance just right for intimacy, and steadily resisted Louise's demands for more frequent trysts.

He carefully and a little sadistically corrected the poems she sent him; "his criticism was most implacable," Brown remarks, "when tact might have been most appropriate." When she complained of his "sepulchral detachment," he told her that "I always found in you a tone dripping with sentiment that watered down everything and spoiled your thought"—a view that Brown, who has little patience for Colet, seems to endorse. Flaubert lost his temper altogether when she maligned Musset, another of her lovers, in a section of her feminist Poème de la femme. "Who appointed us moral overseers?" he asked. "This poor fellow never sought to do you in. Why harm him more than he harmed you? Think of posterity and reflect upon the shabby figure cut by those who have insulted great men.… Posterity is forgiving of misbehavior. It all but pardons Jean-Jacques Rousseau for having delivered his children up to a foundling hospital." Or as Auden wrote in a similar vein, "Time will pardon Paul Claudel/ Pardon him for writing well."

The considerable interest of Flaubert's correspondence with Colet lies less in their emotional or sexual incompatibility than in their continual aesthetic strife. "Ah! Louise! Louise!" he wrote to her in 1853, as their affair was stumbling to a halt. "How can you imagine that a man besotted with Art as I am … whose sensibility is sharper than a razor blade and who spends his life scraping it against flint to make sparks fly … how can you imagine that such a man could ever love with a twenty-year-old heart?" It was the personal nature of her writing that offended Flaubert, who said of the Musset diatribe that "you wrote it from the skewed perspective of a personal passion, ignoring the fundamental conditions of every imaginative work."

Brown identifies two sources for Flaubert's commitment to "impersonality" in writing: his physician-father's "clinical method" and his own struggle with epilepsy—"the explosion of personality in clonic seizures." I suspect that, as with T.S. Eliot, that other apostle of impersonality, Flaubert found confirmation for his "sepulchral detachment" in the teachings of the Buddha, whose statue he kept on his writing table and whose views he laid out in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, the Asian section of which he was working on as he held off the increasingly importunate Louise. Yet another Buddhist fellow traveler, Lafcadio Hearn, made an excellent English translation of The Temptation, complete with scholarly footnotes.

Flaubert's autumnal correspondence with George Sand reprises some of the same conflicts as the Colet correspondence, though on a higher, less emotional plane. Sand admired Flaubert's aesthetic stubbornness amid poor sales and punitive reviews, but she begged him to clarify his attitude toward his characters. She thought he could do so without authorial intrusion. "No, I don't say that you should personally take the stage," she wrote in 1876. "But hiding one's opinion about one's characters and thus leaving the reader uncertain as to what he or she should think is to bargain for incomprehension." Flaubert's noble response matched her didacticism with a higher morality. "You preach in vain," he told her. "I can have no temperament but my own, nor any esthetic but that which derives from it.… As for revealing my personal opinion of the people I put onstage—no, no! a thousand times no! I don't recognize myself as having the right to do it. If my reader does not get the moral drift of a work, then the reader is an imbecile." Sand died while Flaubert was working on the story he thought was more in accord with her wishes, his affectionate tribute to the hopes and sufferings of a dutiful servant, Felicite, the "simple heart" of his title. But it is doubtful that the ending of the story would have pleased Sand, as faithful Felicite, in her death agony, mistakes her stuffed American parrot Loulou for the Holy Ghost.

Flaubert's creed of impersonality has nothing to do with the macho reticence of such self-styled disciples as Hemingway and Dashiell Hammett. He would have been as repelled by Hemingway's stylistic posturing as he was by Merimee's muscular writing on bullfights and Spanish passion; Flaubert's friends Turgenev and Zola were shocked at what Brown calls his "autopsy" of Merimee's prose style. The extinction of authorial personality was a religious tenet for Flaubert, as Erich Auerbach recognized when he referred in Mimesis to Flaubert's "self-forgetful absorption in the subjects of reality" as "mystical in the last analysis."

Flaubert claimed that while writing of the suicide of Emma Bovary, he had "a strong taste of arsenic" in his own mouth. Henry Adams was closer in spirit to Flaubert's asceticism (as he was in much else, including his passion for historians of decline such as Tacitus and Gibbon, his sardonic view of "education," his pleasure in the company of nieces, and his loyalty in friendship) when he advised the "architectural tourist" in austere Norman churches to "read a few pages" of Flaubert's letters or Madame Bovary "to see how an old art transmutes itself into a new one." Adams discerned a spiritual affinity between Normandy and New England, a "relation between the granite of one coast and that of the other." Haunted by his own wife's suicide by poison, the bitter ending of Madame Bovary must have had a particular poignancy for Adams.

Among American novelists, Willa Cather probably learned most from Flaubert. Her favorite of his novels was Salammbô—"I like him in those great reconstructions of the remote and cruel past"—and she achieved something analogous in Shadows on the Rock, her underrated novel of early Quebec. Cather modeled the tripartite structure of Obscure Destinies (as John Hollander has pointed out) on Flaubert's Three Tales. Having dismissed Kate Chopin's The Awakening as a "Creole Bovary," Cather proceeded to write a Bovary of her own, set in Colorado, in her brilliant novella A Lost Lady. By an extraordinary coincidence, while vacationing in Aix-les-Bains in 1930, Cather made the acquaintance of Flaubert's niece Caroline, the same woman who, a lifetime before, had followed her uncle around the garden as he taught her geography with a shovel and a bucket of water.

"It must have immediately become apparent to Caroline," Brown observes, "that she had encountered a most unusual American and, where Flaubert's work was concerned, an interlocutor on equal terms." When Cather spoke of "the splendid final sentence of Hérodias, where the fall of the syllables is so suggestive of the hurrying footsteps of John's disciples, carrying away with them their prophet's severed head," Caroline "repeated that sentence softly: `Comme elle était très lourde, ils la portaient al-ter-na-tiv-e-ment.'" Brown finds in this "Chance Encounter," as Cather memorialized it, a perfect ending for his own remarkable book.

Christopher Benfey, Mellon Professor of English at Mount Holyoke, is the author of Degas in New Orleans (University of California Press) and The Great Wave (Random House).