The set of “Jeopardy!” was given a shiny makeover last year, in preparation for the quiz show’s fiftieth birthday. The new look features that familiar, top-heavy, bubble-letter logo and a gorgeously tacky sunset backdrop that provides an odd companion to the sexless blue-and-white board. In fluorescent spirit, though, the set is unchanged since the 1980s, much like the program itself.

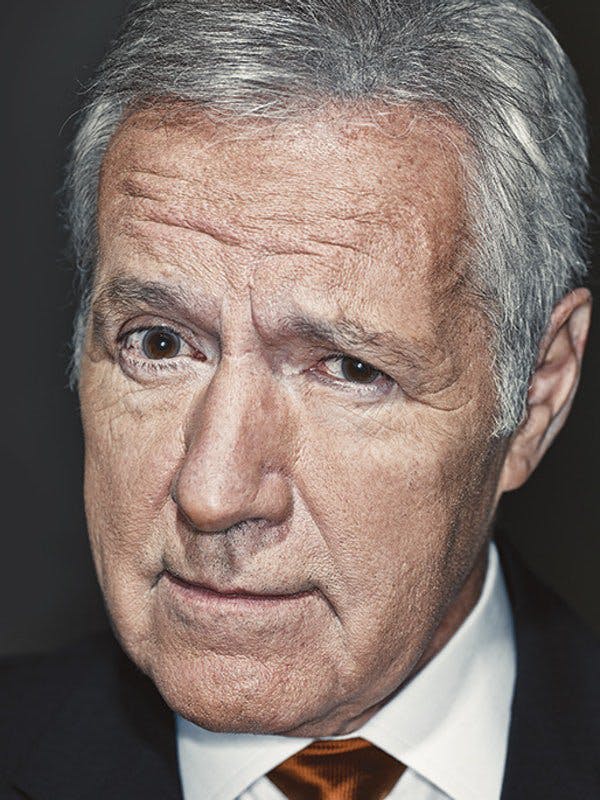

Contestants come and go. Here’s our returning champion. He’s from Maryland, she’s from Chicago. Some, like this year’s star, Arthur Chu, even briefly become big deals. But it is Alex Trebek who has remained the centerpiece. His extended tenure as America’s senior-most faculty member has made Americans forget that he’s playing a part; a few years ago, Trebek was voted the eighth-most-trusted person in the United States, sandwiched between Bill and Melinda Gates. “He’s like a Ward Cleaver figure,” says Ken Jennings, the most successful “Jeopardy!” contestant ever. “But for the past thirty years.” This month, in fact, the host will mark three decades as the face and voice of “Jeopardy!”; like the show’s theme music, he is almost post-iconic, such a known entity that he’s just there.

He might not be there for much longer, though. “Jeopardy!” continues to draw around 25 million viewers per week, making it second among syndicated game shows (behind only “Wheel of Fortune,” which “Jeopardy!” fans dismiss as little better than a televised jumble puzzle). But Trebek has hinted that he will retire when his contract runs out in 2016. Already he has outlasted Jay Leno and now David Letterman as one of the final one-man TV brands from the time before DVRs. Audience shares and attention spans, however, aren’t the only things that have changed during his run. In the Internet era, knowing a little about a lot provides diminished cachet: You don’t have to retain facts when they can just be Googled. These days there’s a throwback charm to the whole “Jeopardy!” enterprise and the appeal, in Trebek’s late-career performances, of a simple job well done.

Watch enough “Jeopardy!” in a row and the call-and-response of the games can become almost meditative. No, I’m sorry, that is incorrect. Who is Paul Revere? That’s today’s Daily Double! Watch ten shows taped over two days, as I did last fall, and you enter a fugue state. Trebek has by now done more than 6,000 shows, read out who-knows-how-many facts. Fact after fact after fact. He is a TV star who presides over an assembly line.

But a funny thing about the audiences at “Jeopardy!” tapings: The faithful pilgrims who’ve come to Sony Pictures Studios to see what it all is like in person—most don’t actually look directly at Trebek. As a loping Brontosaurus of a camera records the action for broadcast, it also pipes footage onto two jumbo screens that face the audience. It’s those monitors that the crowd members keep their eyes locked on, not the man below. Mediated Trebek is the Trebek they are comfortable with, the one they reflexively watch.

The real Trebek does not mind that.

Onto Trebek’s office door is taped a kid-drawn nameplate made out of dot-matrix printer paper. Inside is an accidental museum to the information conveyances and repositories of the late twentieth century. On a credenza sits a late-model Sony TV set, a stack of VHS tapes resting nearby. Next to an electric pencil sharpener is a beautiful, ancient dictionary, the kind with the phyllo-fine pages that used to make a person marvel at how the world’s knowledge could be sliced so thin and served up so fat.

One morning, the featured exhibit sat behind a leather-inlaid desk, thumbing through a reference book.

“I’m re-reading a book called Universe. It’s a history of scientific exploration and great men of science,” Trebek said. “What’s amazing that I’ve discovered—and I’ve come to the conclusion that I’ve gotta do more research on this—is that Alexandria must have been one hell of a place two thousand years ago.”

He peered down and began to read from the old Merriam-Webster.

“Eratosthenes was 276 B.C. to 194 B.C. He measured the circumference of the Earth from the sun’s rays at separated points.”

Trebek closed the book and flipped over a sheet of paper on which the day’s “Jeopardy!” questions were printed. He began to sketch: the solar system.

“He could look at the shadow at noon and see how long it was over here, and he managed to figure out, ‘Hey, the Earth is round.’ And then we went through the Dark Ages where people believed—they got rid of all of this philosophy and all of this great stuff that the Greeks and Arabs had come up with. They decided, well, no, ‘The Earth is flat.’ ”

The pen strokes grew vigorous.

“And then they went back to, ‘The sun revolves around the Earth.’

“Duh!” Trebek said.

Trebek has built his career on an air of erudition. But offscreen he is equally invested in a second persona, one that colleagues say has emerged more in recent years. This other Trebek is “much less of a ‘Masterpiece Theater’ guy,” is how a staffer puts it. “He’s more of a getting-his-hands-dirty guy.”

So even as Trebek might casually draw the solar system during conversation—because of course that’s a thing the host of “Jeopardy!” would do—he also takes pride in noting that he was almost kicked out of boarding school as a boy. He sometimes brags about his breakfast of Snickers and Diet Pepsi and likes to talk about the rec-league hockey games he suited up for with Dave Coulier (the “Full House” star who was not John Stamos, Bob Saget, or an Olsen twin). He has had two heart attacks but sums up his current exercise regimen as “I drink.” Yes, Trebek can describe for you the 1928 Mouton that he once tasted. But, he is quick to joke: “I’m not a true wine connoisseur. I’m just a drinker.”

Fact, according to Trebek: His favorite place in Los Angeles these days is Home Depot. He and his second wife, Jean, whom Trebek married in 1990 when she was 26 and he was a 49-year-old divorcé, live in a nice house in the Valley, and he spends a great deal of time thinking about maintenance and improvements (which he accomplishes with the help of “Manuel and Miguel”). Trebek says that when he gets up in the middle of the night—he has terrible insomnia—he will lie awake for hours plotting how to fix the sliver of light peeking through his window, and all the other home-repair projects he wants to tackle next.

Trebek grew up in Sudbury, Ontario. During his college days at the University of Ottawa, he held down jobs at both a local radio and TV station, scrambling around town to avoid missing classes or shifts. He got his start as a host in 1963, when he was cast to emcee a Canadian program called “Music Hop.” He was 33 when he moved to Hollywood to helm “The Wizard of Odds” on NBC. (Alan Thicke, the Canadian father of famous line-blurrer Robin Thicke, gave Trebek that first south-of-the-border job.) Clips of his early work show a natural performer. All elements of the singular Trebekian delivery—crisp enunciation, acrobatic inflections, hammy dignity—are there, along with a not-yet-faded accent.

When “Jeopardy!” hired Trebek as host in 1984, the franchise was emerging from nearly a decade off the air. The show had been the creation of Julann Griffin, wife of game-show impresario Merv Griffin, who dreamed up the format while quiz shows were recovering from the 1950s cheating scandals at “The $64,000 Question” and “Twenty-One.” Her insight was that the game could not appear to be rigged if you went ahead and gave the answers to the contestants and asked them to supply the questions instead. Trebek added to that his showman’s knack for drawing out contenders and filling silences with easy patter. He quickly propelled “Jeopardy!” to a level of popularity never achieved under his now-forgotten predecessor. (The correct response to a very hard final round clue would be: “Who is Art Fleming?”)

In their early years, quiz shows were a platform for striving immigrants to show themselves as the intellectual equals of establishment WASPs, or at least gain some recognition for their smarts. “Jeopardy!” came out of that tradition, and as mass culture coarsened, it stood as an archipelago of aspirational dweebiness in a sea of hair-metal music videos and prime-time soaps. But if “Jeopardy!” once stood athwart history yelling, “Stop!”—and rewarded those able to recall who originally coined that phrase—there is plenty of fodder for declinists in the gradual devolution of what the show considers cultural literacy.

Today’s games feature far fewer questions in subjects like philosophy or classical music, statistically the most difficult categories. A recent Time study plumbing the trove of “Jeopardy!” data maintained on a fansite called J-Archive showed that references to Albert Einstein peaked 15 years ago; newer episodes reference Justin Bieber more than twice as often. During the tapings I watched, there was a question about twerking, which Miley Cyrus had just weeks earlier brought into the boomer vernacular via her performance at the Video Music Awards. No contestant got a question about Samuel Coleridge correct, which might have been less noteworthy if they hadn’t been so quick to buzz in with “Who is Dan Brown?” on the clue directly preceding it. A recent category—“It’s a Rap”—required Trebek to spit verse: “Ain’t. Nuthin.’ But. A. Gee. Thang,” he gamely recited, his diction as sharp-cornered as ever. It was funny. For the viewer, anyway.

According to head writer Billy Wisse, “Jeopardy!” is merely adjusting along with the evolving canon. His team needs to write the games so that contestants will still have a shot at knowing the answers; just as important, they have to ensure that the people playing along at home still get to feel good about their intellects. “They don’t know as much about Theodore Dreiser as they used to,” Wisse said. “It’s sad, but it’s so big that it seems a shame to mourn for it. There’s not much anyone can do.”

What did Trebek think of that twerking question, I wondered in his dressing room between shows one day. He was on the couch. He indicated that I should sit on a distant chair.

“Well. So,” he said. Then an extended pause. “That’s good.”

Trebek’s considerable charm has an on / off switch that he will flick in the middle of a sentence. Offstage, he creates silences, lets a curt reply linger, answers questions with a sullen “OK.” The later in the day, the more it happens. Trebek shifted into this mode again when I asked him if it might be possible to come hang out with him at the house he spends so much time working on and thinking about. His p.r. team had indicatedbeforehand that it might be a possibility, depending on his mood.

“I’m gonna be so busy because of all the work I’ve got going on,” Trebek began. “We’re doing a new decking around the pool, and I’m gonna have to be working with contractors for the trellis work that I’m gonna do it. This is not a good time, unfortunately.” I got the impression that anytime would be bad, where this particular request was concerned.

Lately Trebek’s insomnia has grown more severe. His hairdresser, Renee, who refers to herself as his second wife, nags him affectionately to take his ZzzQuil, but he forgets. He’ll sometimes have been up for hours by the time he heads to the set. Before the day’s tapings begin, Trebek and the staff of “Jeopardy!” meet in a timeworn room kitted out like a middle-school library, with a whole bookshelf stuffed with bright yellow volumes from the For Dummies series. People who come to work at “Jeopardy!” tend to stay—Trebek and the producers are good bosses, everyone says—so the show’s employees are little older and dowdier than might be found on other Culver City lots. The questions, which Trebek doesn’t write but will edit or spike as he sees fit, have been drafted long before these sessions. This is rehearsal time, and Trebek uses it to go over things like pronunciation and pacing. As he will admit without being asked, he would not know all the answers without the script in front of him.

On the morning I sat in, Harry Friedman, the executive producer for both “Jeopardy!” and “Wheel of Fortune,” was running late. So Trebek passed the time by telling the writers about his weekend. He’d taken Jean to Napa. They’d flown in a 1928 biplane—“I told the pilot afterwards, I love weightlessness in the morning!”—and gone to brunch.

Trebek called to a researcher in a nearby office. “Suzanne? Do me a favor! Google the French Laundry up in Yountville. Find out how much the brunch cost. I think it’s $350,” Trebek said. “I got my money’s worth, ‘cause I was the only one drinking at the table.”

Suzanne, a middle-aged woman in a long skirt, came in with a printout. Fact: The chef’s tasting menu at the French Laundry was currently going for $250.

Trebek’s wife is serious about her church, the North Hollywood Church of Religious Science. While the Trebeks were in Napa, Dr. Eben Alexander, the author of Proof of Heaven, was giving a talk nearby. The couple went to check it out. “That ring a bell with anybody?” Trebek asked. “He’s the doctor who went into a coma for a week . . .”

A writer cut in: “Didn’t they say he was a fraud?”

Trebek looked puzzled: “A fraud? I don’t know. He lied? How could he have lied? It’s his experience.”

Church friends comprise the core of the Trebeks’ social life, he says, a big shift from the bachelor years when he tooled around Holly-wood in a Bentley convertible. Mostly, he unwinds by watching television. “Breaking Bad” and “Deadwood” are recent favorites; the Lakers a constant. During football season, he follows the Redskins, whom he doesn’t think should change their name. “They weren’t called the Redskins because we thought Redskins were terrible; it’s because we admire their strength, their abilities,” he says. In his dressing room one day, Trebek had on Fox News in the background. “Somebody was saying on television a few days ago that the Tea Party is a reflection of the people. There are a lot of people out there who are not happy with the way things are going, and they’ve banded together,” he told me later, though he declined to reveal whom he voted for in the last presidential election and, when pressed, said he’s “apolitical.”

Fact: When Trebek shaved off his moustache in 2001, he did it in the middle of the day, himself, without warning the “Jeopardy!” producers. Renee was alarmed to come in and find him mid-shearing. He just felt like it, he says now. “And it got so much press, I couldn’t believe it. The wars with Iraq or whatever at that time, and people are all in a stew over my moustache. I have one response: Get a life.”

Another fact about Trebek: the “Jeopardy!” theme song, which he has heard tens of thousands of times in his life, never gets stuck in his head, or so he says. The cameras and the crowds do wonders for his disposition. “I’m feeling really good today,” he said at the beginning of one episode. Turning to the contestants, he added, “Let’s get to work, shall we?” It’s that consciously workmanlike quality to the tapings that brings the ancient Greek scientist-citing Trebek into alignment with his Home Depot–loving side. “The best part of the job is the thirty minutes I spend onstage with the contestants running the game,” he told me. “I do—I really do—enjoy talking to the audiences.”

Perhaps for his own sake as much as theirs, then, Trebek chats with crowd members during commercial breaks, inviting them to ask him anything they want. “I’ve been on the air for fifty years,” Trebek told me, “so I’m like a member of the family. Oh, there’s Alex. Well, we’d better get him a drink and get him some French fries or potato chips or whatever. They just want to know if I am in reality the way they perceive me on television. Is he a nice guy or not? Is he aloof or not?” Trebek feels loyalty to his fans—“I don’t have to talk to the audience,” he notes, correctly. But the questions tend to be the same, show after show, and are less than probing. What did he have for dinner the night before? someone wanted to know. He had the halibut, “just for the hell of it.”

What Trebek really loves is doing impressions for the crowd. He makes a study of them; he’ll come into the “Jeopardy!” offices and ask his staff if they’ve noticed the way a certain famous person carries his hands, or if they’ve ever registered the eyebrow tic of an obscure character actor.

“You got spunk. I hate spunk,” he told me one day,out of nowhere, then demanded to know if I could identify the source of the quote.

Nope.

He followed with another line, this one in a different, high-pitched voice: “Oh, Mr. Grant! ...”

Disappointment at my silence.

“Ed Asner as Lou Grant to Mary Tyler Moore.”

It’s impersonations of Hollywood icons that Trebek really nails, though he doesn’t like to let on how much effort he puts into the routines. “I’ve noticed in the last few years, I don’t think I’m very good at them anymore,” he told the “Jeopardy!” audience during one time-out. “Probably a factor of too much alcohol.

“If I could learn to stop drinking the morning of taping, that would help a lot,” Trebek continued. “But you see, um, I have trouble sleeping. Yesterday, for instance, I woke up at two o’clock and was awake until 5:15 and then my alarm went off at 5:25. Today I woke up at 3:00 and was awake until 5:20. . . . I’m of the old school, which says, ‘It’s five o’clock somewhere, so why not now?!’ ”

A beat. Trebek’s comic timing is good. “But I no longer drink when I drive,” he said. “I pull over to the side of the road.”

When Trebek was growing up, he said not long into our first conversation, he wanted to be the prime minister of Canada, or a doctor, or an actor. He likes to tell “Jeopardy!” audiences that because he achieved none of them, he’s a failure. “Gets a laugh,” he told me. By the time I stood in his dressing room during a lunch break between shows one day, I’d heard him say it twice. He was sitting in a white t-shirt, a hint of tummy showing. And so I asked: “Was there any truth to the joke?”

A producer came in. Trebek stood up. “When something is important enough to you, you do it. So obviously if I haven’t done it, it’s because maybe it wasn’t all that important to me.” Button-down on and buttoned, microphone hidden, suit jacket donned and smoothed. “The secret to happiness, of course, is not getting what you want; it’s wanting what you get,” he added.

(Fact: That piece of wisdom, according to Google, originated with one Rabbi Hyman Schachtel.)

Later, I happened to run into Trebek on my way to the set’s parking lot. He usually drives a Dodge Ram 1500, “a half-ton pickup,” as he had noted to me with pride. “I’m not a macho man because it doesn’t have a gun rack. It has a wine rack! Just so that I can drink while I drive,” Trebek joked, recycling a punch line.

But here he stood chatting with a man in a golf cart next to a white Jaguar in the choicest reserved parking spot.

He spotted me and waved. “I’m only driving the Jag today,” he yelled, “because my wife has the truck.”

And with that, Trebek roared off.

Noreen Malone is a senior editor at New York.