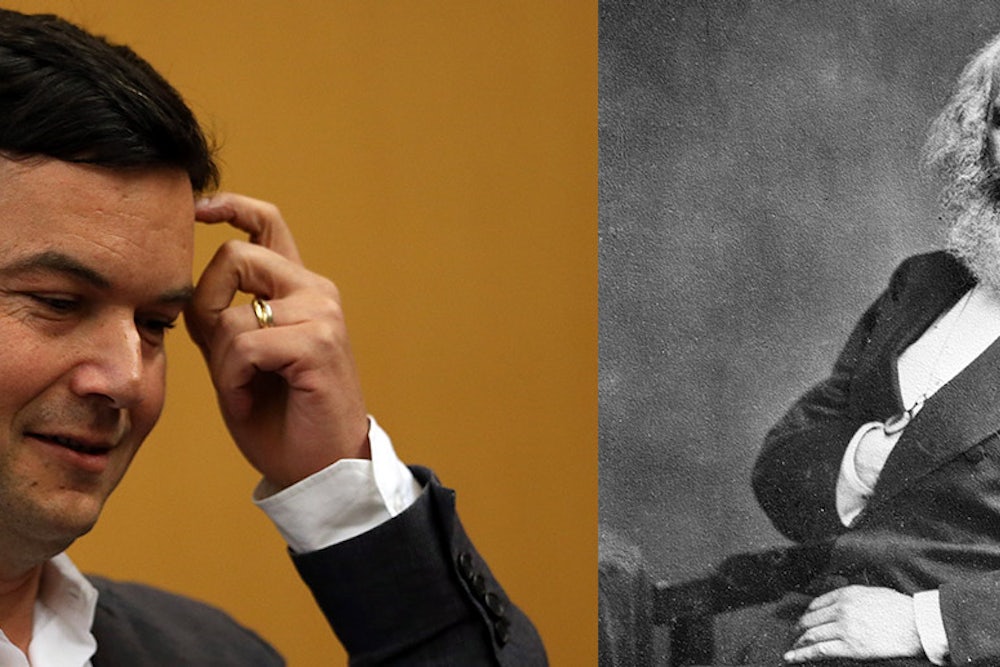

I admire Thomas Piketty’s new book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. I’ve even read it. But I fear that, in his interview with Isaac Chotiner, Piketty was putting on his American readers when he disclaims any interest in Marx’s ideas. He says he “never managed to read” Marx and that Marx’s ideas were “not very influential” on his work and that his book, unlike Marx’s Capital, is “about the history of capital” and that Marx’s Capital contains “no data.” These statements are uniformly false, and Piketty must know it.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, whose title is an allusion to Marx’s work, Piketty discusses Marx’s ideas more than those of any economist except, perhaps, Simon Kuznets, who in the 1950s pioneered the econometric techniques that Piketty has refined. He discusses Marx’s ideas more than those of John Maynard Keynes or any contemporary economist. He acknowledges to Chotiner that he read The Communist Manifesto, but in his books he cites passages and arguments from the first book of Capital and from book three, which Frederich Engels put together posthumously from Marx’s notes, and which is only read and discussed these days by aficionados.

Moreover, Marx’s Capital is the climax in a tradition, beginning with Adam Smith, and dubbed “political economy,” that factored in the historic role of the state in explaining the evolution and workings of capitalism. Piketty writes that he prefers to describe his own work as “political economy” rather than “economic science.” Marx’s work, Piketty knows, was about the history of capital: The last half of the book, parts four through eight, were a history of capital and capitalism.

Does Piketty really believe that Marx, whose colleague Engels had written The Condition of the Working Class in England, did not rely on data? Here’s what Piketty writes: “Marx was also an assiduous reader of British parliamentary reports from the period 1820-1860 … He also used statistics derived from taxes imposed on profits from different sources.” And he cites Marx’s use of “account books of industrial firms.” Piketty thinks Marx ignored some sources, but he clearly recognizes that Marx used data.

Perhaps, Piketty was on the defensive because of the pathetic review on National Review’s blog by James Pethokoukis from the American Enterprise Institute that was titled “The New Marxism.” Piketty is not a Marxist, but, like other European economists and some older American economists (the late Lawrence Klein, among others), he appears to have been engaged and influenced by Marx’s theories. (I once discovered several telltale formulations in the work of Raghuram Rajan, former IMF economist and University of Chicago professor and now head of the Bank of India. When I asked him, Rajan wrote back that he had read Capital and considered Marx “a great economist.”)

Why is it wrong to describe Piketty as a Marxist? Piketty rejects Marx’s “dark prophecy” of the end of capitalism and his rudimentary view of socialism. Marx, Piketty writes, “devoted little thought to the question of how a society in which private capital had been totally abolished would be organized politically and economically—a complex issue if ever there was one, as shown by the tragic totalitarian experiments undertaken in states where private capital was abolished.” On a deeper level, Piketty’s approach to economic history more closely resembles that of Adam Smith or David Ricardo than Marx. Marx analyzed capitalism as a system of social relations—relations of production—that had to be created politically by transforming the old Feudal classes of serf and lord. Marx also wanted to understand capitalism’s particular “laws of motion.” Piketty is concerned only with the latter part of economic history. Capital, in Marx, is a social as well as economic category; in Piketty, it is only the latter.

But Marx’s influence does intrude in Capital in the Twenty-First Century. First, like Marx, Piketty approaches capitalism historically. His book is at once theory and history in the same way as Capital. Second, he does see capitalism as beset with internal contradictions and describes his formula, r>g (the rate of return on assets exceeding the rate of economic growth) as “the central contradiction of capitalism.” Third, he sees his central contradiction, as Marx did his, as a result of the accumulation and concentration of capital. (Marx would add “centralization.”) And fourth, he sees that contradiction as possibly leading eventually to some kind of crisis or requiring a “radical shock” to overcome. Marx, of course, is much more explicit on this last subject than Piketty, but readers who get through the book will recognize this echo and other echoes of Marx in Piketty’s formulations and approach.

Where Piketty specifically engages Marx is on Marx’s theory of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. The rate of profit is profit divided by the sum of the costs of labor, materials, and depreciated plant and equipment. Piketty disagrees with Marx that the tendency is a general tendency—rather he thinks it is a special case—but readers will recognize that Piketty’s general theory of the law of motion of capitalism is meant specifically as an answer to Marx’s. Marx didn’t write about the tendency in any of his published writings, but it appears in his workbooks for Capital, the Grundrisse, and in Engels compilation of Book III of Capital. Marx called it “the most important law of modern political economy.” The formaulations are a little obscure and ambiguous, and I’m never certain I’ve gotten it entirely right, but I’ll try my best without putting formulas on the pages.

Marx thought that an enterprises’ profits were based on the difference between the value of what its workers could produce and their wages. The value of raw materials or the depreciation of plant and equipment was simply passed through to the price of the product. So profit depended on the degree to which capitalists could exploit, in the technical sense, their workers. Marx assumed that as a result of competition, capitalists would try to increase their production by adding new machinery that would increase the rate of exploitation, that is, make workers more productive. But doing that would increase the value of raw materials and depreciated plants and equipment as a proportion of total capital. Imagine 10 workers producing 10 widgets on two machines with five tons of steel. Then imagine the same ten producing 12 widgets on three machines with six tons of steel. Labor’s wages would make up a smaller and smaller percentage of the capital on which the rate of profit was calculated.

If labor’s productivity didn’t increase sufficiently, profits themselves might increase, but the rate of profit would fall.1 That was Marx’s tendency of the rate of profit to fall. If the rate of profit begins falling, capitalists either stop investing, and a crisis results, or they try to raise back their rates of profit by reducing their workers wages, in which case labor goes to war against capital, as happened, for instance, in Great Britain in 1926 when there was a general strike. The UCLA economic historian Robert Brenner has used a sophisticated version of Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit in his book The Economics of Global Turbulence to chart the history of advanced capitalist economies from 1945 to 2005.

Piketty spends four pages analyzing Marx’s theory. Piketty accuses Marx of undervaluing the growth of productivity in his formulation, and Piketty is certainly right. Marx, for one, did not anticipate technology that would lower the cost of capital and raw materials as well as the relative cost of labor. But Piketty’s historically-based objection is that he believes that the rate of return on capital, which is related to the profit, will remain relatively constant except in extraordinary circumstances. As a result, what is likely to happen is that even as growth slows, capitalists will still insist on a five percent rate of return. As a result, their income will expand and accumulate disproportionately as a percentage of annual national income. Marx’s revolutionary end point—where everything devolves into crisis and revolution—is when the rate of profit approaches zero. Piketty’s is when capital grows so large as a percentage of annual income that it absorbs all of national income.

Several commentators, including Robert Solow during his talk at the Economic Policy Institute, have questioned Piketty’s insistence that the rate of return will remain constant, and have suggested instead that it is likely to decline, leading to secular stagnation and recession. That seems to me plausible, as does the view, hinted in Piketty’s analysis of the crash of 2008, that the growing imbalance of income between the one percent and everyone else could produce recurrent financial crises and recessions. These suppositions suggest that in some respects, Piketty may have strayed too far from Marx’s influence or from those Keynesians like Joan Robinson who were deeply influenced by Marx. But one thing is certain: Piketty did read Marx, and did think about him.

OK, one simple illustration: The profit might have been $200 on an enterprise that paid $500 in materials and depreciation and $500 in wages. That’s a rate of profit of 20 percent. The rate of exploitation was 200 divided by 500 or 40 percent. If the capitalist then invested a hundred of those dollars of profit in plant and materials that also increased the rate of exploitation of the same workers from 40 to 42 percent, that would mean an increased profit of $210, but given a total expenditure now of $1100 in wages, material, and depreciation, the rate of profit would have dropped to 19 percent.