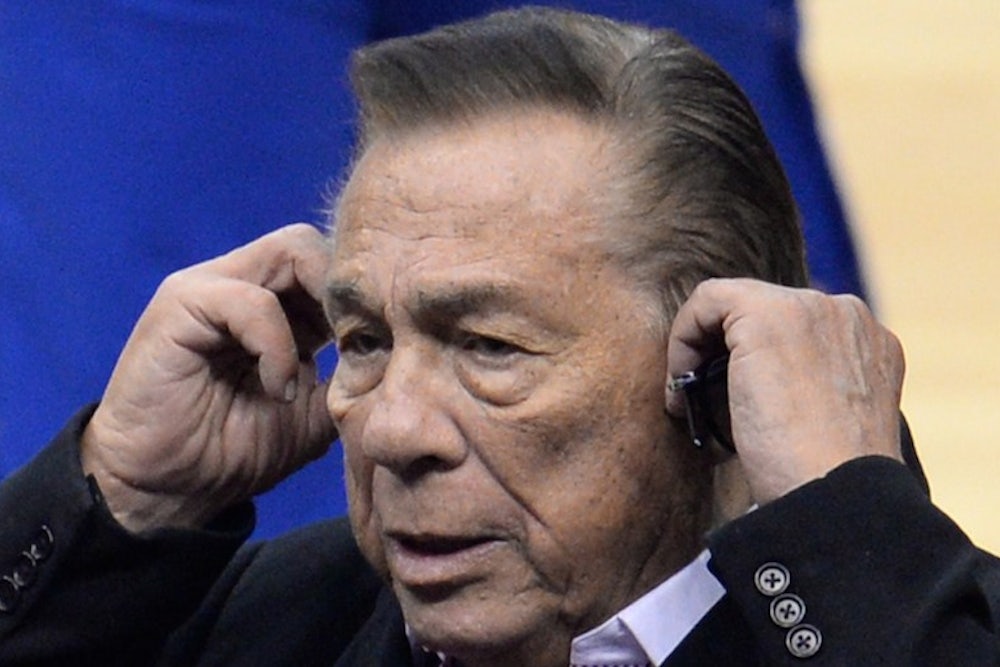

It wasn’t long after this alleged Donald Sterling episode blew up that other members of Sterling’s ethnic group winced that Sterling—born Tokowitz, not that Sterling isn’t suggestive enough—had brought shame to his people. (Or, as the Yiddish phrase goes, Sterling is ein shanda fur die Goyim.) And that was before Deadspin’s extended cut revealed that Sterling’s racism actually extends to some Jews: “You go to Israel, the blacks are just treated like dogs….there’s white Jews and black Jews,” he said, clarifying for his interlocutor that the black Jews are “less than” the white Jews.

It’s sad for all the obvious reasons, but it’s also sad because basketball and the National Basketball Association have historically been a concentrated locus of Jewish-black exchange, and even solidarity. Due to patterns of racial acceptance in the United States, Jews broke into mainstream basketball first and have attained more positions of power, frequently using those hard-fought positions to open the sport up to blacks. If the relationship has occasionally veered toward the paternalistic, it has nearly always been well-meaning. Of course, when Sterling did things like compare his team to a Southern plantation (allegedly), he went well beyond even the worst kind of aloof liberal condescension.

Basketball was founded by a Canadian at a YMCA, and spread throughout more rural parts of the United States—think of the sport’s popularity in states like Kentucky and Indiana—through the Ys. But its urban variant was pioneered about a century ago by the lower-class ethnic groups of lower Manhattan, most of all Eastern European Jews who benefited from settlement houses and gymnasia built for them by their wealthier, more assimilated German co-religionists. The shortest player in the Basketball Hall of Fame is Barney Sedran (born Sedransky), one of whose early teams, known as the Dizzy Izzies, compensated for their small sizes by incorporating concepts from lacrosse such as backdoor cuts, no-look passes, and frequent ball movement. These principles—an essential part of the game even today—were codified into something known as the City Game by coach Nat Holman, whose City College squad won both the NCAA and NIT titles in 1950.

Holman’s starting five that season comprised two blacks and three Jews, and for a time, these were basketball’s dominant on-court ethnic groups. Jews also climbed the rungs to positions like executives (the first league commissioner was Maurice Podoloff), broadcasters (the term “swish” was coined by Olympic track star turned Madison Square Garden announcer Marty Glickman), and above all coaches. Basketball’s all-time greatest coach, the Boston Celtics’ Red Auerbach, fielded the first all-black starting five in 1964 and in 1966 chose as his successor his star center Bill Russell, making Russell the NBA's first black head coach. Four years later, a New York Knicks squad that starred white Princeton grad Bill Bradley and black Grambling State grad Willis Reed won a title as one of the sport’s most beloved teams under the direction of coach Red Holzman, who learned the City Game while running point for Holman’s CCNY team. Three years later, a black player known for a more isolation-heavy type of play, Earl Monroe, helped the Knicks to a second title. A few years later, Woody Allen published an extended riff in praise of Earl the Pearl.

Thereafter, as Jews ascended the socioeconomic scale and assimilated, things got a little more complicated, as basketball Jews assumed more obvious positions and as black players began to assert their own culture. Agent David Falk was indispensable to helping Michael Jordan become the first athlete to be his own brand. The milestone for the introduction of hip-hop culture into basketball was 1991’s Fab Five at the University of Michigan, whose coach, Steve Fisher, was a Jewish man who seemed uncomprehending yet tolerant of his players’ attitudes. A decade later, things were not so amicable between Philadelphia 76ers superstar Allen Iverson, who embodied the newly unabashed expression of urban culture in the NBA, and his coach Larry Brown. (Time was that it was the Jewish players whom out-of-touch white guys pegged as déclassé: 50 years before, while a player at North Carolina, Brown instigated this legendary brawl with Duke’s Art Heyman, a rival from back in Brooklyn.) By far the most prominent Jew in basketball has been recently retired NBA commissioner David Stern, a political liberal (albeit an anti-union one) who frequently condescended toward the overwhelmingly black players in a way that suggested failed attempts to do the right thing.

Today, the NBA commissioner is Adam Silver, a Jewish kid from Westchester whose father was friends with Stern. A large proportion of the owners—larger even than in the other leagues—are Jews, from old-school ones like Chicago’s Jerry Reinsdorf and Indiana’s Herb Simon (another City College kid) to newer ones like Dallas’ Mark Cuban and Golden State’s Joe Lacob. Miami Heat owner Micky Arison is from Israel, where basketball rivals soccer as the most popular sport.

In Israel on Tuesday, an Ethiopian-Israeli member of parliament named Shimon Solomon called on Silver to remove Sterling from the NBA, writing: “As a Jew, as a citizen of a country founded on the ruins of racism in Europe, it hurt me to hear Mr. Sterling.” He signed the letter, “a black Jew from Israel.” Shoring up Jews’ bona fides as good basketball citizens is far from the most important reason why Silver should grant Solomon’s request. But as a white Jew from America, I’d be lying if I didn’t say that it is yet another reason I hope he does.