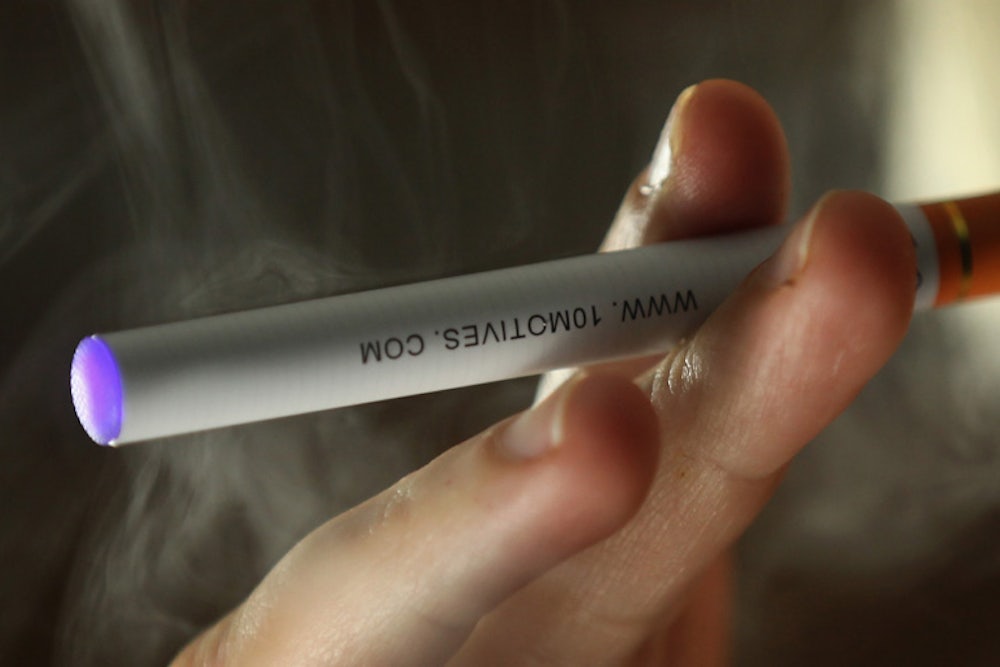

Last week the Food and Drug Administration filled the regulatory vacuum surrounding electronic cigarettes, battery-powered devices that convert a solution of nicotine into a vapor.

The agency draft regulations would ban sales to youths but allow flavorings and set a two-year timeframe for approval of existing vapor products.

Growing in popularity among smokers—about one in five tried an e-cigarette between 2010 and 2011, the latest years for which the Centers for Disease Control has data—the current market is estimated at $2.2 billion in the U.S., up from under $1 billion two years ago.

Reactions to the agency’s draft proposal prompted a fresh round of nervous commentary on the devices. And, much of it, though by no means all (the New York Times is a refreshing exception), gave greater consideration to the speculative harms surrounding e-cigarettes than to their considerable potential for benefit.

A recent article in The New Republic by pediatric cardiologist Darshak Sanghavi gave disproportionate weight to e-cigarette skeptics’ unsubstantiated claims. We felt a more detailed picture was warranted.

As Dr. Sanghavi rightly notes “Despite years of research, tons of spending on everything from nicotine patches to nicotine gum, and admonitions from physicians, no one has figured out a great way to help smokers quit.”

In the U.S., this is true. In Sweden, by contrast, there has been marked success with snus, a tiny pouch of tobacco that sits between a person’s cheek and gum. For 50 years its use by Swedish men has been associated with world-record low rates of smoking and smoking-attributable deaths, including lung, oral and throat cancers as well as cardiovascular events.

Electronic cigarettes might well be a good way, perhaps a great way, to quit but, as Sanghavi points out, good epidemiological data does not yet exist. Yet the study in JAMA Internal Medicine that he cited, which purported to show the ineffectiveness of e-cigarettes in quitting, did not evaluate the products in a meaningful way.

Researchers from the University of California at San Francisco looked at 949 smokers who were surveyed online in 2011 and 2012. Only 88 smokers used e-cigarettes in 2011; one year later nine had quit, which was not statistically different from the smokers who had not vaped.

First, quitting is not the only measure of success: merely switching to e-cigarettes spares smokers the carcinogenic tar, not a trivial health advantage. Moreover, only eight percent of the 88 vapers expressed an intention to quit. If they had no desire to quit, there is no reason to think that use of e-cigs would make it more likely. In fact, the authors reported that “intention” to quit did predict quitting while electronic cigarette use, per se, did not.

Another important facet of the debate, as Sanghavi says, is the worry that vaping will serve a gateway function to actual smoking. Many critics of e-cigs consider this prospect ample reason to curtail marketing and availability to adults.

But how realistic is the gateway phenomenon? The National Youth Tobacco Survey reveals that e-cigarette use (as little as a single puff within the last month) among high school students almost doubled from 2011 to 2012, from 1.5 percent to 2.8 percent. However, the same survey showed that cigarette use declined from 14.6 percent to 11.8 percent at the same time.

The central question is whether the small group of teens who reported trying e-cigarettes move on to smoking conventional ones. At this time, there are no reliable signs of this.

To date, then, data suggest that increased exposure to e-cigarettes isn’t encouraging more teens to smoke. Yet the numbers of youthful vapers are still so small that it’s too early to make definitive claims about the relationship between teen vaping and smoking.

Epidemiologists must continue to collect data on patterns of vaping and smoking among teens and adults. But they will also be following the advantages. After all, people switch to e-cigs because they are less hazardous than conventional ones. They don’t combust tobacco leaves, so vapers are not exposed to carcinogenic tars and harmful gases that cigarettes produce.

What’s more, e-cigarettes have advantages over nicotine patches and gums: They provide a quicker fix because the pulmonary route is the fastest practical way to deliver nicotine to the brain, and they offer appealing visual, tactile and gestural similarities to traditional cigarettes.

This is why so many public health experts are enthusiastic about the harm reduction properties of e-cigarettes. Harm reduction is an approach to risky behavior (smoking, in this case) that prioritizes minimizing damage (by cutting out tobacco combustion) rather than eliminating the behavior (by tolerating, even encouraging, vaping).

"For the first time in a century, we have an appealing alternative way to give addicted current smokers a satisfying way to give up their combusted products," said David J. Abrams, Professor in the Department of Health, Behavior and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Abrams is saying that e-cigs are safer for smokers, not “safe.” The risk, if any, of long-term inhalation of propylene glycol, the common substrate used for the nicotine solution, is not known—the devices have simply not been around long enough. In limited exposure, however, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration generally regards propylene glycol as safe; it is used in toothpaste, asthma inhalers and many other foods and cosmetics. Still, epidemiologists should monitor its effect on health, if any, over the long term.

And while there are also traces of nitrosamines, which are known carcinogens, they are present at levels comparable to medicinal products, such as nicotine gum and patches, and at concentrations 500 to 1,400 times lower than in regular cigarettes. Cadmium, lead and nickel may be there, too, but in amounts and forms considered nontoxic. Also, e-cigarettes do provide nicotine, which can be addictive, but the health effects of nicotine are generally benign.

There are no data on the long-term use of e-cigarettes. Some risks may well be uncovered, but the almost certain likelihood of advantage to smokers will be too.

The crux of the issue is not, as Sanghavi put it, whether e-cigs encourage non-smokers to start up versus whether they help people quit. It’s not “either-or.” We need to know whether smokers who switch to e-cigarettes have lower levels of disease than their counterparts who continued smoke and how the health of committed vapers compares to those who wean themselves off e-cigs entirely. We also want to know if e-cigarettes are introducing non-smoking teens to cigarettes.

It’s not clear what the FDA will do with such information when, at least a decade from now, it becomes available. One hopes the agency wisely weighs the yet undiscovered costs with the still-to-be confirmed long-term benefits.

Sally Satel, M.D., is the W.H. Brady Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Brad Rodu is a Professor of Medicine at University of Louisville.