Is Jo Becker trying to position herself as the Sacha Baron Cohen of journalism? Or is Forcing the Spring, Becker’s account of the court battles that led to the invalidation of Proposition 8 in California, offered as a piece of serious reporting? It is a conundrum that the book’s 437 pages fail to answer definitively.

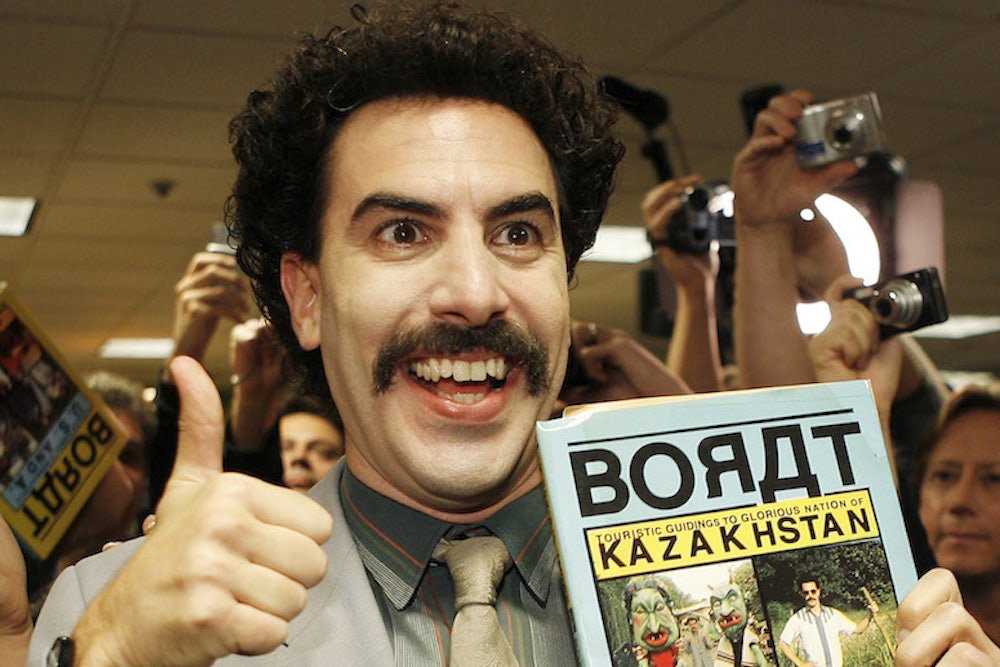

Sacha Baron Cohen has made an art form out of punking his audiences. The formula is a simple one. He commits to an over-the-top character—Borat from Kazakhstan; Brüno the Austrian fashionista—and then films himself with ordinary people, who become unwitting cast members in the scenes he orchestrates. His success lies in his capacity to turn his subjects into caricatures, inducing them to display their flaws, vulnerabilities, and idiosyncrasies and then editing them to appear two-dimensional and foolish. Baron Cohen is a talented performer, and Borat alone has grossed a quarter of a billion dollars. But the exploitation inherent in the work—its reliance upon exposing the less flattering qualities of its subjects and then placing those faults in artificially sharp relief—has always turned me off. I don’t like to see people get set up.

Reading Forcing the Spring, I could not shake the feeling that Becker, too, was engaged in an elaborate attempt to punk her audience. Becker replaces Baron Cohen’s absurd foreigner with the softer cliché of the invisible, embedded reporter, but the effect is largely the same: She has written a book that seems designed to dupe major figures in the LGBT world into squaring off against each other in grand combat—the cage-fight-turned-soft-porn-session in Baron Cohen’s movie Brüno that incites a predictable and hoped-for riot among the Arkansas spectators. As with staged cage-fights and riots, no one who accepts the assigned roles in this drama emerges looking good—except of course for the author, who can affect a look of bemused detachment, do the interview circuit, and marvel at how everyone is overreacting.

This is an unworthy way to tell an important story. The Prop 8 litigation was one of the major events in the current phase of the marriage equality movement. It deserves to be recognized and celebrated in realistic terms, not set up as a target of ire. And Human Rights Campaign (HRC) President Chad Griffin—the moving force behind the Prop 8 lawsuit and Forcing the Spring’s main character—will only suffer from being cast as the redeemer of a lost and wandering movement, the righteous warrior vanquishing the sanctimonious Pharisees in Becker’s breathless messiah narrative. No one could survive being measured against such claims.

Becker is not subtle, opening the book with a sledgehammer passage likening Griffin, a rich, white political insider with a powerful media operation behind him, to Rosa Parks, the radical black NAACP volunteer whose act of defiance transformed her into a civil rights icon. That comparison now serves, unavoidably, as the first point of reference in most discussions of Forcing the Spring. Becker’s repeated likening of the two (she reprises the theme late in the book, on the eve of the Supreme Court argument) conjures the absurd image of Griffin waving his arms and crying “I’m just like Rosa Parks! I’m just like Rosa Parks!”—a mantra, as the late David Rakoff once wrote, “about as descriptively apt as the wishful four-year-old at Halloween who announces ‘I’m a scary monster!’ to every grownup proffering candy.” A journalist seeking to build a proper stage for Griffin’s accomplishments would never set the man up so unfairly. An author seeking to whip a crowd into a Borat-style death match, however, could hardly do better.

There are smaller but equally heavy-handed “tells” throughout the book. Griffin lands on the cover of The Advocate magazine’s “40 under 40” list while the lawsuit is underway, and Becker observes that “the success of the trial was starting to bring the establishment around.” Of course, these splashy “Top” lists are public relations exercises to a significant extent, and when Griffin is not busy being Rosa Parks in this unkind narrative, Becker makes clear that Griffin sits atop that particular establishment. One presumes that he helped to orchestrate his own valorization on that list, as honorees sometimes do. Why depict Griffin as a faux-outsider to the P.R. world, if not to parody his promotional efforts?

Or there is the passage in which Becker describes the decision by lawyer Ted Olson to take on the case. Olson proclaims, “I will not just be some hired gun. I would be honored to be the voice for this cause,” only to explain three sentences later that the cost of this not-a-hired-gun honor will be a discounted fee of $2.9 million plus expenses. David Boies, too, agrees to sign on for the “deeply discounted fee” of $250,000 plus expenses. (Public records indicate that the totals ran north of $6 million.) Becker must be lampooning these rich mega-lawyers for their capitalist rendition of pro bono legal representation, and she is not gentle.

But it is the subtler elements of Becker’s burlesque messiah tale that are the most striking. Forcing the Spring exploits some of the very tactics that antigay forces regularly rely upon, and it uses those tactics to minimize or denigrate the work of nearly everyone in the LGBT world other than Griffin and his compatriots. It is difficult to imagine a more sinister provocation of people who have spent their lives in the fight for equality.

The first among these tactics is the causation fallacy. Opponents of marriage equality regularly structure their arguments around wild claims about the consequences to marriage and society if gay couples are allowed to wed. A favorite example, appropriately enough, involves the Low Countries: The Netherlands legalized same-sex marriage in 2001, the argument goes, and the overall marriage rate plummeted thereafter. Never mind that marriage rates in The Netherlands declined at a fairly steady pace both before and after 2001. Post hoc ergo propter hoc! Who needs serious arguments about cause and effect? More cinematic variations on this theme often describe the natural disasters and terrorist attacks putatively caused by America’s gay-loving culture. The tiresome need to dismantle these causation fallacies—persistently, meticulously—is one of the defining experiences in this type of advocacy. Becker herself describes the phenomenon in relating the testimony of economist Lee Badgett during the Prop 8 trial.

Forcing the Spring exploits this causation fallacy relentlessly when presenting Chad Griffin as the gay savior. Early in the book, Becker entices the reader with an “audacious” goal that Griffin and his team have set: “to flip public opinion on same-sex marriage from majority opposed to majority support by the time the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, in the hope that a more hospitable political climate would make the justices feel more comfortable ruling their way.” A worthy goal, indeed, and the very reason that long-time LGBT advocates have sought to secure marriage equality in a critical mass of states before presenting a constitutional claim to the Supreme Court. But can one P.R. team really flip nationwide public opinion on such a contentious issue? Yes, they can! Or so Becker invites her readers to believe. By the closing chapters of her story, after a slew of marriage equality victories in other states, public opinion has shown “a remarkable transformation” with support for marriage reaching 58 percent in one poll on the eve of the Supreme Court argument. And how did this remarkable transformation occur? The only actors on the stage are Griffin and his team, who stand alone to claim credit for this audacious triumph in public opinion.

Speaking of those other marriage equality victories, how were they achieved? Before Griffin assumes the leadership of the Human Rights Campaign, marriage equality just kind of happens in this book. In Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, and Iowa, equal marriage rights appear on the landscape like natural phenomena—extrusions of igneous rock that pop out of the ground spontaneously, without agency or origin. But following Griffin’s ascension to the helm of Gay Inc. (a term that Becker uses early in her narrative to disparage the major LGBT organizations but abandons when Griffin assumes his new role), statewide battles over marriage in Washington, Maryland, Maine, and Minnesota, along with a judicial election in Iowa, have suddenly become “Chad’s Big Test.” But what is the test? Is it for Griffin to make wise decisions about how to direct HRC’s resources as part of the team efforts on the ground in each of these states? Or rather, is this a chance for Griffin to seize the laurel wreath of victory with his singular actions? Need one ask? Griffin is once again the only protagonist on stage, and the extraordinary victories of the 2012 election cycle are all about Griffin: “Four for four, plus they had saved the judge in Iowa. Talk about a great atmosphere going up to the Supreme Court.” Let same-sex couples marry in the Netherlands and the whole country falls apart, but put Griffin in charge in America—in Becker’s narrative—and same-sex magic happens. Post Griffin ergo propter Griffin.

And all those states where marriage equality spontaneously appears bespeak another tactic that Forcing the Spring appropriates from the antigay playbook: erasure. To be gay in America, even today, is to struggle against forces that seek to erase your existence. This has always been the defining mode of oppression levied against same-sex intimacy, “the love that dare not speak its name.” That is why Becker’s erasure of all non-Griffin actors is such a supremely provocative act. Beth Robinson of Vermont Freedom to Marry, now a Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court, who championed equality among the Green Mountains; Richard Carlbom of Minnesotans United for All Families, the self-effacing leader who held together that successful coalition; Lisa Goodman, the powerhouse president of Equality Delaware who impelled the winning effort in The First State; and the countless other leaders, foot soldiers, and volunteers who fought these battles—all have spent their lives contending with a world that wishes to deny their existence. When Becker writes these people out of history, she levies a primal attack. In this sense, Becker’s mass-erasure is an even greater assault than her appalling treatment of Evan Wolfson, the brilliant and indispensable dynamo in the marriage equality struggle whom Becker depicts as a mustache-twirling villain who should be humbled rather than heeded. To be attacked, at least, is to be acknowledged.

And no erasure in Forcing the Spring quite compares to that of Shannon Minter of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, one of the country’s leading civil rights attorneys and a true gentleman of the LGBT movement. Minter represented the couples in the original lawsuit that won marriage equality in California, the 2008 victory that made possible Griffin’s rise to prominence, yet he appears nowhere in the tale. Instead, Becker uses Terry Stewart of the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office as the instrument for Minter’s deletion. Stewart, herself a great lawyer and distinguished public servant, partnered with Minter in the California lawsuit, but Becker presents Stewart and her office as the sole force behind that triumph. The cruel irony is that Minter, among all LGBT national leaders, worked the hardest behind the scenes to foster a productive relationship with the Prop 8 legal team, who came to the table with an excess of arrogance and a dearth of expertise on LGBT issues.

Becker’s depiction of the lawyers in Forcing the Spring is the last Borat-style provocation that I will describe here, though there are many others. Here, too, there is a rich and complicated story that Becker pushes aside. I have called the Olson & Boies team arrogant. Well, so what? David Boies is one of the nation’s most accomplished trial attorneys, and Ted Olson and Ted Boutrous occupy the highest echelon of the elite Supreme Court Bar. If anyone has earned the right to be arrogant, one might think, it is they. And there is an important fact about “arrogance” in the legal profession: believing that you are right can help to make you right. Legal practice differs from science and medicine in this respect. A doctor cannot cure infectious disease by applying leeches, no matter how committed he is to the idea that it should work, but a lawyer’s conviction that she is right can have a real impact upon the receptivity of a court or a jury to her arguments. Arrogance is certainly not the only mode in which an advocate can be compelling, but there is no denying that it works for some lawyers.

The problem at the outset of the Prop 8 lawsuit, rather, was that the Olson & Boies team seemed to have no appreciation for the role of expertise in LGBT litigation. “This is simple: equal means equal,” they essentially said. In the early meetings between the Prop 8 lawyers and the LGBT groups, and in Olson’s first appearance before Chief Judge Walker, the Prop 8 team gave no confidence that they would put on a compelling trial (which Olson initially opposed) or that they were ready to answer the complicated set of questions about identity, sexual privacy, procreation and child-rearing, and sex and gender that a marriage-equality lawsuit puts on the table. That is one of the primary reasons that the LGBT groups sought to intervene in the case. And even after the judge turned the groups away, they contributed their knowledge to the trial effort. Thus, the distinguished roster of expert witnesses whose testimony Becker describes in detail were identified for the Prop 8 team by the LGBT groups, the result of decades of litigation in similar cases in which they honed the right message and found the best messengers.

Becker captures none of this interplay at the inception of the suit. What she describes, instead, is Olson holding forth on a series of the most obvious Supreme Court precedents like a sage divining the pronouncements of the Oracle at Delphi. “Chad listened, mesmerized. Olson was talking about some of the murkiest areas of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence, and divining the true meaning and extent of the justices’ opinions was akin to what an archaeologist faces when trying to decipher recently unearthed ancient cave drawings. The markings were there, but what did they really mean?” Imagine a newcomer seizing a tablet of hieroglyphs out of the hands of a seasoned Egyptologist and saying, “No one seems to realize that these words are made of pictures, not letters,” and you will get some sense for the grating quality that this passage has for career-long experts.

But focusing only on the provocation that Becker offers in this passage misses a deeper truth. There is something important, and wonderful, about a bunch of newcomers who view equality in such straightforward terms. David Sedaris captures this sense of the virgin traveler exploring a well-trod path when he describes one of his first sexual experiences in Naked, his noted collection of essays: “‘You kids think you invented sex,’ my mother was fond of saying. But hadn't we? With no instruction manual or federally enforced training period, didn’t we all come away feeling we’d discovered something unspeakably modern?” The story here is not one of Olson’s unparalleled brilliance, but of the newness with which he and his team came to the arguments and the earnestness of their conviction that the federal courts would be ready to accept them. Subsequent events have partially validated the judgment of the LGBT groups on the purely strategic question: The Court declined to reach the merits in the Prop 8 challenge, and it is the outcome in the Defense of Marriage Act litigation that has catalyzed a wave of victories in marriage-equality cases around the country. But the moral judgment of a conservative establishment figure like Olson that marriage equality is a constitutional imperative has contributed to a transformation in the national conversation to an extent that the LGBT groups did not fully appreciate at the outset.

And that, in the end, is the true measure of this book’s affront. Jo Becker’s Borat-style performance is a scourge for the people whom she purports to celebrate, not merely those whom she erases and caricatures. Griffin has made a major contribution to the marriage-equality effort over the last five years, turning his lawsuit into the most successful public relations vehicle that the movement had seen before Edie Windsor’s triumph over DOMA. Forcing the Spring threatens to divide the LGBT world into an artificially polarized group of defenders and attackers, making it impossible for Griffin to receive his due. The Human Rights Campaign—which has joined with the Gill Action Fund and Freedom to Marry over the years in making vital contributions to the political struggle for marriage equality around the country, particularly through the work of its national field director Marty Rouse—is forced either to double down on this book and thereby threaten relationships within the LGBT community or else repudiate it and risk undermining the signature achievement of its new President. So far, neither HRC nor Griffin has handled the challenge well, I regret to say. The quieter actors in Becker’s story are put in a similarly unfair position. Bruce Cohen, the Hollywood producer and key supporter of the Prop 8 effort, is a gentle and earnest man, and while I have never met Rob Reiner, I am confident that he is every bit the mensch he appears. It would be an injustice for Becker’s manipulative book to push these men and their comrades into an angry, defensive crouch.

The best response to Forcing the Spring is to refuse to take the bait. To paraphrase Eleanor Roosevelt, Jo Becker cannot punk the LGBT world without their consent. The power of this book lies only in its ability to provoke. As history and journalism, Forcing the Spring would be a spectacular embarrassment.

Two years from now, Jo Becker may pull a Joaquin Phoenix and emerge from her book tour with a hearty laugh and a new story to tell about how her extended parody has allowed her to cast aside the constraints of the beltway insider. If so, then we can all debate the morality of this new form of Borat journalism. In the meantime, there is more work to do in the fight for equality, and a mighty army of unheralded angels ready to join the struggle.