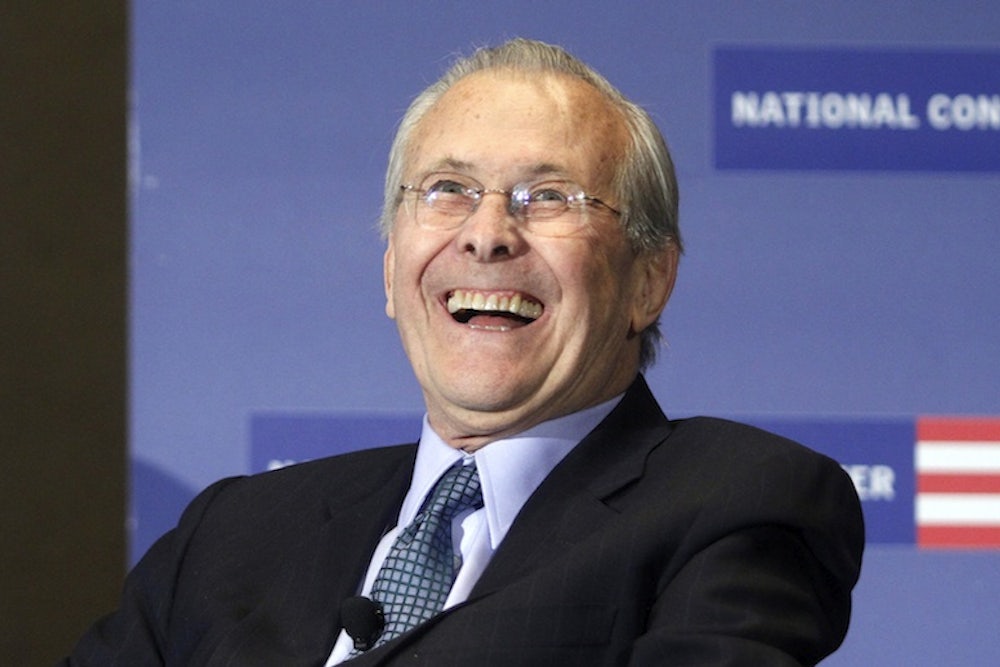

For the past four years, Donald Rumsfeld has been cheerfully defying the assumptions of our public culture of confession and forgiveness. By now Rumsfeld’s errors as secretary of defense have been exhaustively documented: focusing on Iraq rather than Al Qaeda, misjudging the existence of WMDs, sidelining the advice of high-ranking military officers, providing too few troops for the Iraq invasion, remaining blithe as the country spiraled into chaos, and refusing to listen to allegations of torture. By all rights, he should be repentant or, as he was after his resignation, invisible. But since 2010 he’s reemerged, with two books, a website, a charitable foundation, a witty, avuncular manner, and no demonstrable remorse. He is simply, astonishingly, unconcerned, his motto the same as 11 years ago when he dismissed reports of looting in Iraq: “Stuff happens.”

What to make of someone who creates mistakes of this magnitude and escapes regret? Errol Morris, whose documentary of Rumsfeld, The Unknown Known, opens this week, tries to explain the puzzle through interviewing Rumsfeld and examining his memos as secretary of defense. The logic behind Morris’s approach, that analyzing Rumsfeld’s words will provide a key into the man, is a watered-down form of textual analysis that’s become a staple of political writing. For exemplars of the genre like Bob Woodward and Mark Halperin, as well as Rumsfeld’s biographer Bradley Graham, politics is personal rather than sociological, a matter of the actions of individuals rather than larger historical and cultural forces. What this approach leaves Morris with is a highly sentimentalized portrait: Rumsfeld as an outsized villain, whose career arc is characterized by the all-purpose word “ambition” and whose decisions and motivations remain largely opaque. “I fear I know less about the origins of the Iraq war than when I started,” Morris writes in The New York Times. To Prospect Magazine, he acknowledges that “I did like [Rumsfeld] and I am appalled and frightened by him. His unbelievable narcissism, vanity, I don’t even know how I would describe it.” To Rolling Stone, he describes his documentary as a “horror movie” and says that Rumsfeld is “untouched by history.”

Actually, history is exactly what Donald Rumsfeld has been touched by, to a far greater extent than Morris appears to realize. Like most analysts who prioritize personality over context, Morris relies on information provided by his subject, rather than asking where Rumsfeld might have acquired some of the assumptions on which he operates. Viewed through Morris’s personalized lens, as a wily old man outfoxing his interrogator through word games, Rumsfeld remains elusive. Yet, regarded in the context of the social and cultural forces that reshaped postwar America, he is a comprehensible and even predictable quantity. His rise to power was not an aberration of personality; in fact, it has considerably more broad and depressing implications for our political history. Rumsfeld is, above all, representative of a strain of conservative reaction to an increasingly diverse, liberalized country—and his career trajectory serves as a map of its consequences.

Rumsfeld was born in 1932 in Evanston, Illinois, on the Northern edge of Chicago, at the time a hub of confident, patriotic, Midwestern capitalism founded on grain, cattle, and industry. Read historically, Rumsfeld’s was a childhood caught uncomfortably between early-century provincialism and late-century nationalization. Born too late to serve in World War II and too early for the baby boomers, Rumsfeld was just in time to form the vanguard of postwar America’s new meritocracy, pushed east by the economic boom and inclusive government policies that helped integrate the country’s disparate regions. He went to Princeton on a wrestling scholarship, benefiting from the college’s new efforts to recruit graduates from public high schools. Eight years after graduating Princeton, Rumsfeld was elected to represent his home district in Congress, where he served for six years before moving to Richard Nixon’s administration, which was staffed by many Midwesterners, Southerners, and Westerners of his own generation and background. There, Rumsfeld hired Dick Cheney, another American from Flyover Country gone east: born 1941 in Wyoming, attended Yale, dropped out because he “didn’t like the East,” and eventually returned to Washington.

The timing here is significant. Rumsfeld and Cheney came to power just as the patriotic assumptions they’d grown up with, products of pre-war isolationism and postwar prosperity, began crumbling in the upheavals of the period: Vietnam, the New Left, and Watergate. Forty years old, a Midwesterner raised on traditional values, Rumsfeld was caught between the old WASP elite, with their sense of public service as noblesse oblige, and the baby boomers, with their appreciation of diversity and skepticism of authority. “Don always said he went to Princeton on a scholarship,” his wife told Bradley Graham. “So he’s got that edge. He’s wary of those who think they’re better.” Rumsfeld’s friend Cheney described the anti-war rally that set him forever against the New Left in the following terms: “We were the only guys in the hall wearing suits that night.”

A consequence of Rumsfeld’s and his allies’ anti-elitism was that they mistrusted the Washington institutions that they had been appointed to manage, viewing them as liberal, insular, and in need of change by hard-charging outsiders. These were men who saw themselves as carrying frontier virtues of thrift, efficiency, and small government individualism into Washington, D.C., on a mission from their increasingly conservative constituents to save them tax dollars. Rumsfeld was appointed by Nixon to reorganize the Office of Economic Opportunity, a Great Society program that as a congressman he had originally voted against funding in the first place. He was equally suspicious of the military culture when he first became secretary of defense in 1975. According to Admiral James Holloway, who served under Rumsfeld, “It was as if he had made up his mind that he should assume that he could not believe what his chiefs were telling him. It soon became obvious that a response at odds with the secretary’s preconceived position was to be avoided.”

One of the preconceived positions of Rumsfeld and his allies was that American foreign policymakers had been spooked by the anti-Vietnam activism of the late 1960s into losing their moral mettle. In Cheney’s view if not in Rumsfeld’s, Vietnam was a winnable war, were it not for Washington timidity. In 1976, during his first stint as defense secretary, Rumsfeld vociferously opposed an arms treaty with Moscow. Thirteen years later, at the close of the Cold War, he sounded a similar theme, in a speech included by Morris in his documentary: “We’re going to have to make a judgment as to what role our country ought to play, and a passive role would be terribly dangerous. I mean, who do we want to lead—provide leadership—in the world? Somebody else?”

Neither Rumsfeld nor Cheney were political philosophers—they were practicing politicians with a focus on foreign policy and inherited beliefs that altered relatively little throughout their careers. But it’s helpful to clarify their views by looking at the more carefully delineated ideas of the conservative cohort with whom they associated in the '70s, '80s and '90s. Their writings can be found in any random issue of National Review or The Weekly Standard, and many of them haunted Republican administrations from Nixon through Bush II: Paul Wolfowitz, Norman Podhoretz, William J. Bennett, Robert Bork, Harvey Mansfield, Kenneth Adelman, Richard Perle, Irving Kristol, and the still influential William Kristol. Their ideas were responses to the changes in American society during the late 1960s, including the growth of government, a waning of patriotism, an aversion to militarism and the rise of skepticism and relativism. Where others saw progress or decline, they saw opportunity: a chance to take control of the government and change course. As Irving Kristol put it in a 1978 essay in The Wall Street Journal: “I don't think morality can be decided on the private level. I think you need public guidance and public support for a moral consensus.”

These were thinkers for whom decisive action tended to outweigh democratic processes. Professor Harvey Mansfield, who received the National Humanities Medal from George W. Bush in 2004, wrote a 2005 book called Manliness, which he defined as “confidence in a situation of risk,” arguing that the concept was being destroyed by our gender neutral society. Robert Bork, whom Nixon had appointed attorney general because of his willingness to fire the special prosecutor investigating Watergate, wrote in The Tempting of America: The Political Seduction of the Law, “Moral outrage is a sufficient ground for prohibitory legislation. Knowledge that an activity is taking place is a harm to those who find it profoundly immoral.” Most of these men were signatories on the statement of principles for the group Project for a New American Century in 1997: authored by William Kristol, it advocated “a Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity” that, it acknowledged, “may not be fashionable today.”

In other words, these were not traditional, small-government conservatives like Barry Goldwater, or East Coast moderates like George H.W. Bush. They were people who’d grown up with mid-century values and tried to impose them on a later society. Rumsfeld’s aide Douglas Feith summarized this perspective, commonly known as neo-conservatism, to Bradley Graham when he described his boss as a “radical conservative.” This style of radicalism existed on the outskirts of the mainstream Republican Party in the 1980s and 1990s. It wasn’t until 2001—under an inexperienced president with a chip on his shoulder against the establishment, who styled himself a transformative figure—that it percolated to the highest levels of power. As of November 2000, judging by polls, most Americans’ main priority was for their president to continue the eight-year economic boom they had been enjoying. Americans voting for Bush tended to want their taxes kept low and the federal government to continue a generally conservative position towards marriage and abortion. What they got instead was an administration staffed by a suggestible president and ideologues ready to challenge the existing system.

Their influence was strongest when it came to foreign policy: spearheaded by Cheney in the vice presidency and Rumsfeld at the Defense Department, and assisted by Wolfowitz, Perle and Adelman. Yet it percolated throughout the administration, as suggested by an anonymous comment by "a senior adviser to Bush"—widely believed to be Rove—to journalist Ron Suskind regarding regime change in Iraq: ''We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out.”

Viewing Donald Rumsfeld through these lens clarifies traits and decisions that are difficult to account for through straight “textual” analysis. His skepticism about facts is the product of a lifelong distrust of entrenched institutions run by people who haven’t made it on their own. His contempt for critics is a contempt for people who haven’t taken action and made decisions. (“The credit,” he says in the 1989 clip about the end of the Cold War, “belongs to people who are carped at and criticized and said ‘oh my goodness you’re war mongers.’”) His reckless policy decisions are a result of his belief in the need for sweeping transformation by individuals. His lack of regret is a principle as much as a personality trait, a badge of honor worn by a cohort of people who see themselves as presiding over a society gone soft.

Morris takes the title of his documentary, The Unknown Known, from the torturous, obscurant syntax Rumsfeld tends to use when defending his own actions, specifically a monologue from a 2002 Pentagon briefing to the press:

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

In fact, contra Morris's title, Rumsfeld is a “known known.” Where Morris errs is to think he can take the measure of his man through words, since words exist for Rumsfeld as weapons in the struggle against doubters and carpers like Morris. The key to Rumsfeld lies elsewhere, in a culture clash that occurred forty years ago when men armed with drive, talent, and a specific set of values—men convinced of their own rightness, and impervious to contradictory information—came to Washington to change it. Retracing their trajectory makes for unpleasant viewing, but their significance is profound. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, the Department of Homeland Security, warrantless surveillance—we live in the world they helped create.