Last month, as the East Coast was pounded by winter storms and the West Coast by drought, “Meet the Press” decided it was time once again for a climate-change debate. The NBC show predictably invited “two people on opposite sides of the issue,” as host David Gregory put it his introduction to the segment. One was Marsha Blackburn, the Republican congresswoman and vice chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee who, if not qualified to speak authoritatively about climate change, at least influences climate policy (albeit to the detriment of the environment). But her sparring partner that morning wasn’t someone of officially commensurable stature—not a Democratic member of Congress, a prominent climate scientist, a green-NGO head, or even Al Gore. Rather, the man invited onto our most venerated political talk show to defend the scientific consensus was a part-time actor with a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering: Bill Nye, the Science Guy.

Nye did exceptionally well, which shouldn’t surprise anybody who has followed his recent return to public life. He didn’t convince Blackburn of the reality of climate change, but that’s not the metric by which we judge these duels. Rather, Nye did everything you’re supposed to during a televised exchange of talking points: He spoke in digestible, declarative sentences, returning over and over to concrete examples for his arguments. More important, he kept is cool. When Blackburn cited a couple of PhD dissenters, he instead let the ostensibly objective moderator interject: “I’m sorry, congresswoman. Let me just interrupt you,” Gregory said. “You can pick out particular skeptics, but you can’t really say, can you, that the hundreds of scientists around the world who have looked at this have gotten together and conspired to manipulate data.” From there, it was all Nye scoring points while Blackburn mumbled semi-coherently about the “benefits of carbon and what that has on increased agriculture production.”

In today’s YouTube-ready debate contests, that’s considered a win. “Bill Nye Scolds GOP Congresswoman,” Time reported. “Bill Nye Schools Marsha Blackburn,” The Raw Story declared. Mother Jones began its analysis with, “Bill Nye is getting good at this.” Even the conservative Washington Times could only muster that Nye and Blackburn “don’t see eye to eye.” The media response was similar to just weeks earlier, when Nye took on “young-Earth creationist” Ken Ham in a debate, at Kentucky’s Creation Museum, over the origins of life. So one-sided was that victory that the biggest criticism of Nye was whether he should have participated at all, thereby granting undue credence to creationists and helping to fund the museum’s planned Noah’s Ark theme park.

Despite his superficially flimsy qualifications, Nye, who did not respond to interview requests, has emerged these last few months as perhaps the left’s most celebrated public advocate for scientific rationalism—more successful, so far, than the legions of more accomplished experts to come before him. As the Washington Post’s Scott Clement put it, the Nye-Blackburn “meeting puts in stark relief how much the scientific community has failed to communicate their message on global climate change. Perhaps Nye—who has perfected communicating complex subjects to children—will have more success.”

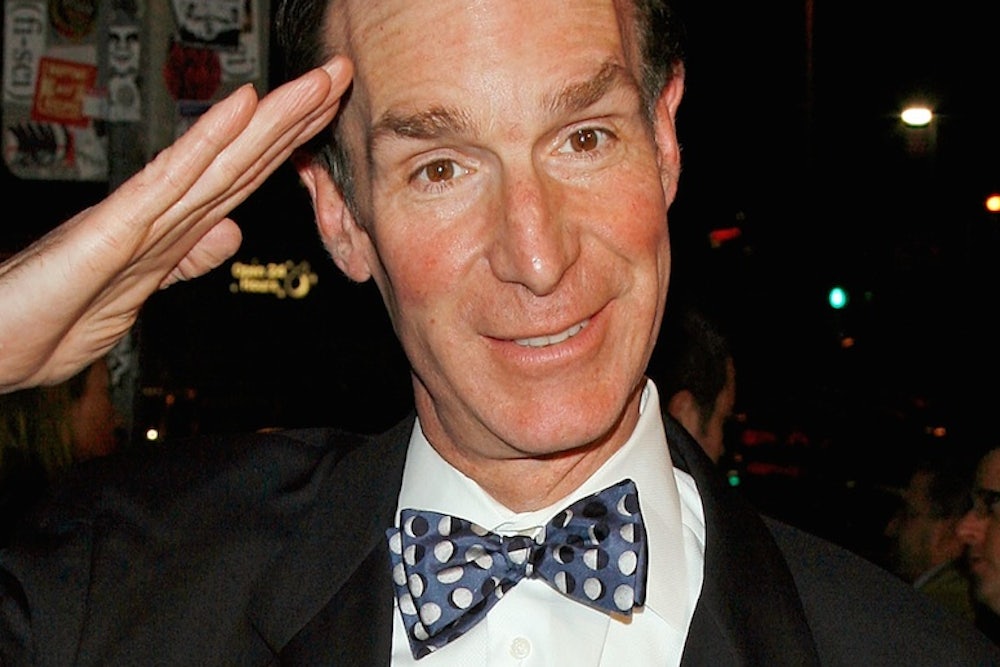

The “Meet the Press” and Creation Museum appearances are part of a broader cultural renaissance for the former host of “Bill Nye, the Science Guy,” a popular PBS Kids show for much of the 1990s, and the fawning doesn’t end with the press. Policymakers sing his praises as liberally as liberal pundits, with one White House official even telling Mother Jones that President Barack Obama himself “lights up when he sees Bill.” A recent photo provided proof of it:

A @BarackObama sandwich-selfie at the @WhiteHouse, earlier today with Bill Nye @TheScienceGuy pic.twitter.com/rEdWtoh2zx

— Neil deGrasse Tyson (@neiltyson) March 1, 2014

That this selfie is being shared with Neil deGrasse Tyson, a bona fide astrophysicist, says a lot about Nye’s skyrocketing credibility. It’s also a bit bizarre. How did a man who has been out of the public eye for over a decade—aside from the occasional TV cameo—become the political left’s foremost spokesman on climate change? And more important, is this genial, bow-tied eccentric really the most qualified and effective person for the job?

William Sanford Nye was born in Washington, D.C., in 1955 to two World War II veterans (his mother was a code breaker). After graduating high school in 1973, he attended Cornell University, where one of his professors was the late, legendary astronomer Carl Sagan. After graduating in 1977 with a B.S. in mechanical engineering, he moved to Seattle and took a job with Boeing. By day, he was the model of a dignified 9-to-5 engineer, developing a hydraulic pressure resonance suppressor still used today. But by night, after winning a Steve Martin look-alike contest in 1978, he began performing stand-up comedy. In 1986, he signed on as an actor and writer for a local comedy show, “Almost Live!,” broadcast on Seattle’s NBC affiliate. It was there that he got his moniker.

Within a few years, in 1993, the newly christened Science Guy was host of his eponymous show, and it didn’t go off the air until half a decade and a hundred episodes later. Before long, “Bill Nye, the Science Guy” was consigned to the mausoleum of Millennial nostalgia, a cultural icon recalled in the kinds of conversations that also touched on Super Soakers and “Legends of the Hidden Temple.” But although Nye was no longer performing in prime time, singing about air pressure to the tune of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” he never left the world of science education. In the years since his show ended in 1998, he has quietly entered the realm of public policy, setting himself up for the resurgence he enjoys today.

In 2005, Nye became vice president of the Planetary Society, one of the country’s largest interstellar-science NGOs. Founded by Carl Sagan in 1980, the society engages in public outreach to promote space exploration, as well as funding research and other efforts that will “seed” further extra stellar exploration. After serving five years, Nye became executive director of the society in 2010. In 2012, he spearheaded the “Save Our Science” campaign, an effort to have Congress to increase federal appropriations for planetary science to $1.5 billion annually (thanks in part to these efforts, the appropriation is now close at $1.345 billion). As an Obama administration official told Mother Jones, for a while now Nye has been “instrumental in helping advance some of the President’s key initiatives to make sure we can out-educate, out-innovate, and out-compete the world.” He just hasn’t been doing it on TV, until recently.

But if Nye’s years of quiet advocacy offer some justification for his Sunday-morning bookings, they don’t quite make sense of his sudden, broad embrace by the left. That’s because Nye’s renewed celebrity isn’t predicated exclusively on his resume, which is still a mystery to most, or on any superlative prowess as a debater. It doesn’t even have to do with shifts in the media landscape. Rather, it’s the result of something much more emotional than all of that.

The most cynical explanation for the Nye Moment is that it’s just the latest symptom of a culture long guilty of conflating celebrity with authority—or worse, that it’s all just generational nostalgia, fueled by the supposed navel-gazing of Millennials who have finally emerged from political puberty. But the cause is more complicated, more deeply rooted in how the left engages in debates over scientific reality.

In the early aughts, fighting battles with the righteous assurance of scientific consensus made happy warriors of leftists. It was fun to poke holes in creationist talking points; while frightening, there was a motivating urgency that came with yielding the newest evidence for man-made global warming. While it was apparent, even then, how stubborn science skeptics could be, it hadn’t sunk in yet how resistant to rational persuasion they would prove to be. The endurance of people like Ken Ham to Marsha Blackburn—forever repeating the same pseudo-rational “objections” with unjustified confidence and unbothered smiles—boggles even the most cynical liberal. Decades of proof, the prognosis worsening by the year, and what does the rational world have to show for it? Nothing.

This has given way to a profound sense of frustration and exasperation. A decade ago, the climate-change debate was about what would happen if we didn’t act. Now, it’s how much we can prevent even if we acted now, which everybody knows we won’t: Ninety-seven percent of climate scientists may agree that humans are causing the planet to warm, but too many Republicans on Capitol Hill do not. It seems that nothing short of the worst actually occurring will get through to the skeptics, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the likes of Sarah Palin and Rush Limbaugh saw Los Angeles underwater and still managed to declare it “hysteria.”

Bill Nye calls his new life as a political pundit a “patriotism.” It’s a war he probably won’t win. If the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change can’t convince the diehard climate-change deniers, the Science Guy probably doesn’t stand a chance. But his performance so far hasn’t disappointed, and that’s exactly the point: It’s a performance. That may be exactly what the rational side, exhausted from years of outrage and alarm, needs today. If the deniers cannot be reasoned with like adults, then at least let’s be entertained by the dismantling of their arguments and exposure of their ignorance—if only to make us laugh, and thereby preserve our sanity. And given that reasoning, who better to debate these intransigent skeptics than an impossibly patient ex-comedian who not only made science fun for children, but made their parents laugh, too?