Most educated Americans can recite the names of at least a few of the principal figures of twentieth-century art—Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Jackson Pollock, maybe Jasper Johns—but ask about the architects of the same era and the only name you are almost guaranteed to hear is Frank Lloyd Wright. He may be the only architect (besides Thomas Jefferson, celebrated for different reasons) whose visage and buildings the U. S. Postal Service repeatedly commemorates. It is as if Wright were the architect who best represents the United States in the eyes of itself.

A survey of all the thought-provoking, eye-grabbing architecture of the last one hundred years would suggest that Wright’s persistent celebrity is a bit mystifying. True, he was what pundits today call an innovator. True, he built more than five hundred buildings, which is, for a firm with only one principal, a lot. But mostly what Wright built in his seventy-year-long practice were single-family dwellings, many of them small. Most of his larger projects are not exactly accessible: his consummate masterpiece, the Imperial Hotel in Japan, was demolished in 1967; another, the Larkin Building in Buffalo, fell to make way for a parking lot; the Marin County Courthouse is off the beaten track (though it does appear as a set in the futuristic dystopian film Gattaca). To get to Wright’s sublime Johnson Wax Building, you need to drive for one and a half hours north from Chicago to Racine, Wisconsin; to Fallingwater, more than an hour southeast from Pittsburgh. Only the Guggenheim Museum in New York is easily accessible and widely visited. Most of Wright’s hundreds of houses that survive remain in private hands.

An energetic self-promoter, Wright led the kind of dramatic, occasionally salacious life that has inspired many a biography and even a novel or two, but neither his tantalizing affairs nor his narcissistic flamboyance quite explains his ongoing celebrity: plenty of egotistical, charming, adulterous, self-promoting architects have failed to earn a fraction of the public recognition that Wright receives. So how are we to account for his extraordinary fame?

Wright was born and spent much of his career in the Midwest during the years when the idea of American exceptionalism and the concomitant search for a genuinely American identity prevailed. Early on, he joined a cadre of Chicago-oriented intellectuals who derided the East Coast’s Eurocentrism and believed that the responsibility fell to them to develop a culture that embodied all that was uniquely, quintessentially American, which to them meant a brave, democracy-loving people inhabiting a spreading landscape, governed largely by individual freedom and personal self- expression. In Wright’s Prairie Houses of 1900 to the mid-1920s, most of which are in the Midwest, he gave architectural form to his vision of a dignified life for the contemporary American family. Extraordinary houses slung along wind-swept prairies promised refuge and the opportunity for self-actualization. Wright expressed his ideal of domesticityin the Prairie Houses’ woody crafted interiors, fireplace-core, and low-pitched roofs extending dramatically into overhanging eaves; he celebrated individual freedom with light-filled, flowing living spaces that spill out from the fireplace-core into the land in several directions. A truly American architecture, Wright maintained, was above all horizontal: it deferred to the Big Country’s golden valleys and endless skyways.

It was the publication in 1943 of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead that elevated Wright to the status of an icon of American culture; Rand publicly admitted that her hero and protagonist, Howard Roark, was a thinly veiled portrait of Wright. Rand’s Roark was a visionary hero who embraced the opportunities that democracy and freedom allowed: the lone cowboy but civilized, doing things his way, telling the (in Wright’s words) “truth against the world.” No living public person so succinctly embodied America’s exceptionalist aspirations. That perhaps explains why Wright’s architecture, art, furniture, art collection, graphic design, and more have been, over the years, the subject of literally hundreds of exhibitions in the United States and abroad, including ten times (ten!) at the New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Now, with the mounting of yet another exhibition of Wright’s work at MoMA, it is fair to ask: again? Is there something in Wright that we have not seen before? This time the occasion is MoMA’s felicitous acquisition, jointly with Columbia University, of the entire Wright archive, which had been languishing in suboptimal conditions at the underfunded Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in two of Wright’s former homes—Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Taliesin West, in Scottsdale, Arizona. It is a coup for both MoMA and New York City to obtain Wright’s extensive archives, and reasonable to expect some kind of public feting of the acquisition. But behind the walls of “Frank Lloyd Wright and the City: Density vs. Dispersal,” a small show of spectacular drawings of his designs for various skyscrapers and the model for his imaginary Broadacre City, one can practically hear the curators at MoMA and Columbia flogging themselves, trying to come up with something new to say.

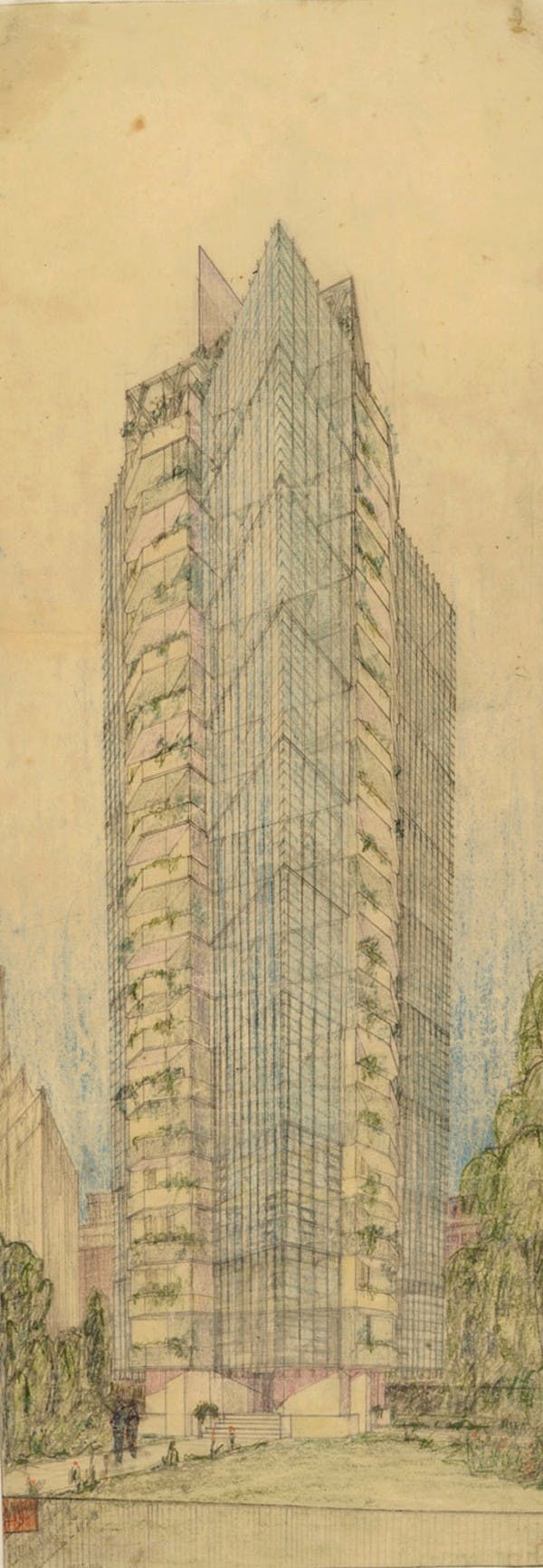

They fail, but that doesn’t mean that the show should be missed. That Wright designed skyscrapers throughout his long career is not generally known, and the exhibition contains several superb hand drawings, better than any drawing by Ellsworth Kelly or Robert Ryman or many other works on paper that MoMA exhibits as art. Wright’s skyscraper designs beautifully illustrate his lifelong project of integrating structure, form, and ornament to create what he called an organic architecture, drawn from and integrated into the natural world.

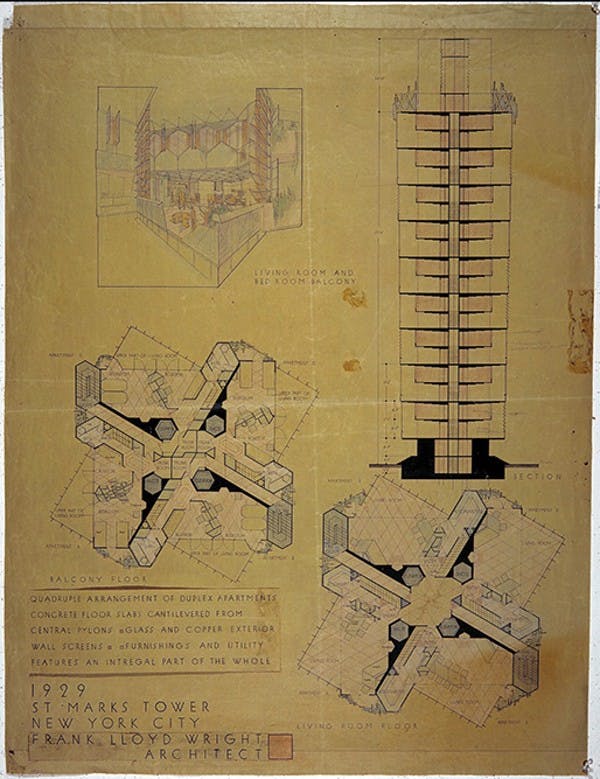

Just as the amphitheater is Greek and the stadium is Roman, the skyscraper is American: it is this country’s unique contribution to architecture, born in Chicago (stubborn New Yorkers disagree) of the three-way marriage of land speculation, newly available technologies for the mass production of steel, and the invention of the elevator. As Wright’s self-stated mission was to originate a singularly American architecture, he could scarcely have ignored the form. And let’s be clear: except for two executed projects, the Johnson Wax and the Price Tower (also off the beaten track, in Bartlesville, Oklahoma), Wright’s unbuilt skyscraper designs cumulatively represent but a tiny handful of unexecuted projects in an immensely prolific, seventy-year-long career.

When Wright turned his attentions to the skyscraper, as he did intermittently, he in no way embraced the classic urban vision of America’s high-rise essence or future. His goal instead was to find the skyscraper’s essential form, as he believed he had found in his Prairie Houses. He rejected the steel frame with its neutral, stacked grid of unarticulated pancake-like floor plates, which facilitates the kind of characterless and easily rentable spaces that developers continue to build. At the time, and indeed until recently, when the demands of sustainability have pushed large firms to rethink the tower’s form, the skyscraper was not a terribly interesting intellectual or design problem.

For Wright, tall buildings must be, like short buildings, organic. Wright was convinced that for humans (“for man,” as Wright would say), the only correct architecture is elicited from and alludes to the habitats in which we evolved. His use of complex geometries, richly textured handmade and mass-produced materials, and techniques of spatial organization all alluded to people’s experiences in the natural world. Doing this in relatively small houses was one thing, but to accomplish it in a skyscraper was quite another.

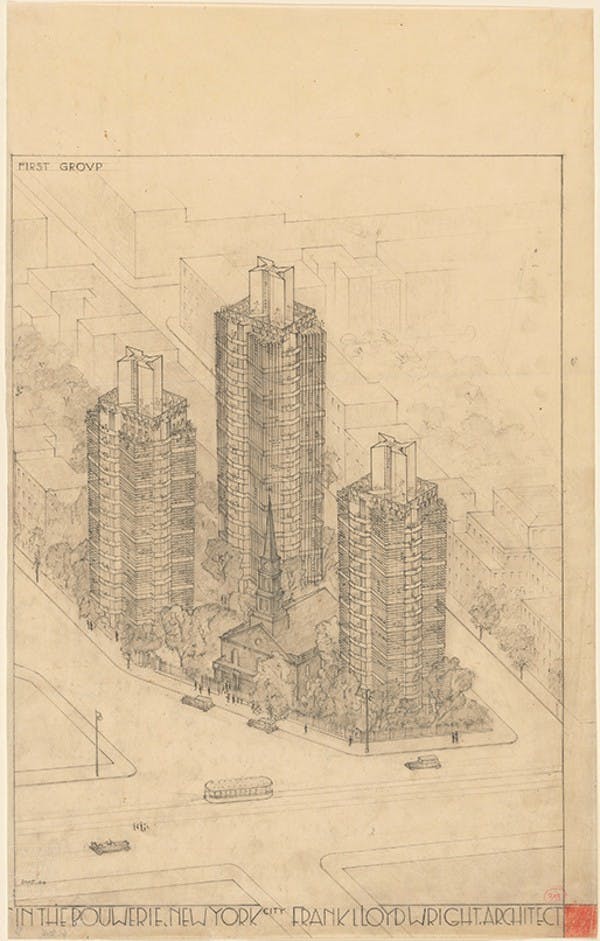

The solution came as early as his spectacular unexecuted design, begun in 1927, of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie in New York City, for which the main conceit was a central core with floors cantilevered off it, like branches encircling the trunk of a tree. This trunk core would be the principal structural element and contain the building’s circulation and services, and the depth of the floor plates would taper like branches from their base at the center to the building’s periphery. The floor plans, in contrast to the typical steel-frame tower’s loft interiors, balanced the enveloping enclosure of rooms with the flowing, expansive vistas of the open plan; its complex geometries of triangles and rotated squares derived from natural forms. In subsequent iterations of the St. Mark’s project, the Price Tower and the Rogers Lacy Hotel in Dallas, Wright demonstrated that he had found a way—if not a cost-efficient way—to maintain an intimate scale in a large building. He accomplished this by developing a consistent, abstract geometric vocabulary and threading it through every aspect of the design, from floor plates to dinner plates. In these projects Wright accomplished vertically the kind of sheltering, liberating, spatially complex interiors that he had achieved horizontally in the Prairie House designs.

Wright’s utopian vision for urban America in Broadacre City is as underwhelming as his tower designs are admirable. The inclusion of Broadacre’s twelve-by-twelve-foot model fails to generate the dialogue about “density versus dispersal” that the exhibition’s title wanly suggests. Broadacre City offers a frighteningly reactionary, and economically unviable, Jeffersonian vision of American society. In it, cities would “disappear.” (Wright’s manifesto, The Disappearing City, was published in 1932.) Every American family would be given a one-acre plot of land and, preferably, a Wright-designed “Usonian” house, an affordable iteration of his more luxurious Prairie Houses. Residents would be mostly auto-dependent, though organized into self-sufficient communities, arrayed along an endless succession of four-square-mile grids, a dimension that Wright lifted from Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase.

MoMA’s juxtaposition of Wright’s tower designs with the Broadacre City model generates no tension between density and dispersal—there is no density here, there is only dispersal. Wright’s ideal skyscraper, including the occasional one that erupts from the flat-lining Broadacre City, belongs not among its peers but should stand alone as “a tree that escaped from the forest” to offer an elevated vantage point onto the surrounding terrain. Anything but urban, Wright’s skyscrapers were beacons, the better to see the American prairie’s big skies and infinite horizons.

The exhibition’s formalist vertical-horizontal opposition of Wright’s tower designs with the model for his naïvely conceived Broadacre City is a misfire. For educational and thought-provoking purposes, it would have been better to ditch the Broadacre model and use the ample real estate it occupies to exhibit skyscraper designs by other architects—by Wright’s colleagues, such as Mies van der Rohe and Gordon Bunshaft, and by practitioners of our own day, such as Norman Foster and Frank Gehry. That would have elucidated how radical Wright’s skyscraper designs were when he designed them, and remain today.

So the U. S. Postal Service version of Wright’s celebrity is partly correct: in addition to being a flat-out great architect, Wright, in his person and in his work, concretized a powerful strain of American romantic idealism that lives on even today, to our benefit and our detriment. But Wright’s architectural vision lives on for another reason. Writers such as E. O. Wilson, Stephen Kellert, Esther Sternberg, and others have established today what Wright intuited: that people respond to buildings that allude to or offer experiences also found in nature. Wood is different from steel. Texture, ornamental or material, helps to maintain a human scale. Jay Appleton proposed that people respond best to landscapes that offer both prospect and refuge, which some analysts have found embedded in Wright’s interiors. As contemporary architects struggle with density in our rapidly climate-changing, ever-exploding world, they would do well to learn at least this lesson from Wright’s vision.

Sarah Williams Goldhagen is the architecture critic for The New Republic and the author of Louis Kahn’s Situated Modernism (Yale).