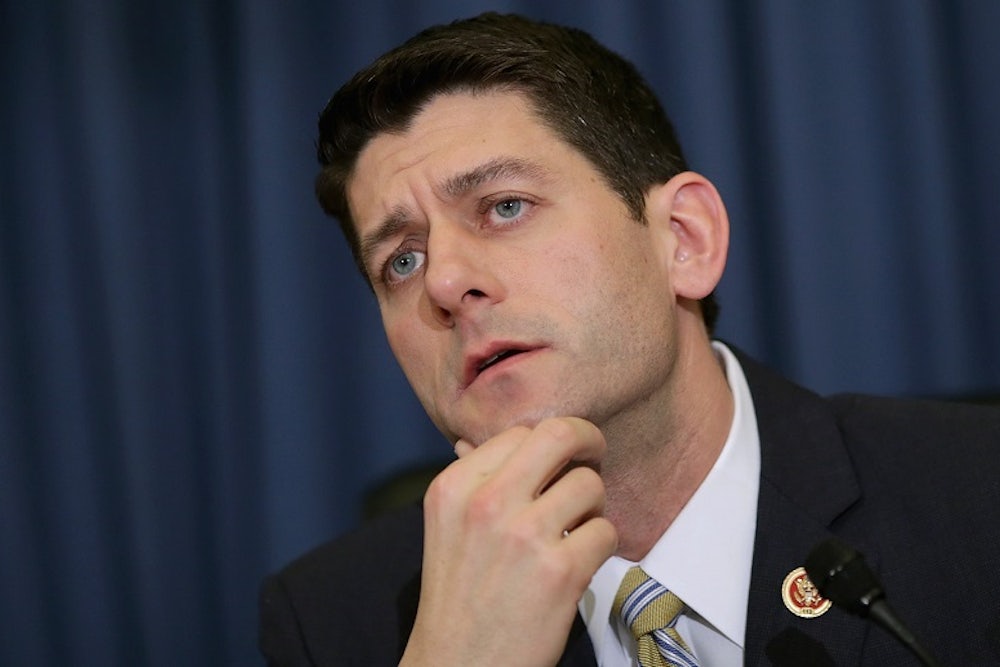

Some controversial comments by Paul Ryan have Republicans on the defensive again. On Wednesday, while appearing on Bill Bennett’s syndicated radio show, Ryan said “We have got this tailspin of culture, in our inner cities in particular, of men not working and just generations of men not even thinking about working or learning the value and the culture of work. There is a real culture problem here that has to be dealt with." Later, while discussing programs like food stamps and Medicaid, he added “When you question this war on poverty, you get all the criticisms from adherents to the status quo who just don’t want to see anything change. We got to have the courage to face that down, just as we did in the welfare reform of the late 1990s and if we succeeded we can help resuscitate this culture and get people back to work.”

Ryan’s interview drew immediate and sharp criticism from liberals, who saw in the comments yet another instance of Republicans blaming poverty on poor people—and, in particular, poor people of color. Ryan walked back his comments a bit on Thursday. He and his defenders said he was merely pointing out what even many liberal scholars acknowledge: People who grow up in low-income neighborhoods are more prone to choices and behaviors that prevent them from holding steady jobs, making money, and lifting themselves into the middle class.

Whichever interpretation is closer to the truth, the real question is what Ryan proposes to do to help poor people. The answer is—not a whole lot.

Ryan’s antipoverty agenda consists primarily of tearing down existing programs. He’s made clear his philosophy many times—most recently, in a 204-page report on the War on Poverty that the House Budget Committee released on March 3. Ryan thinks the programs in place today create a “hammock” of poverty—turning millions of Americans into moochers, sitting at home collecting checks from the government and foregoing work. That’s why his budget proposals have repeatedly called for massive cuts to such programs—$3.3 trillion in total to Medicaid, Pell Grants, food stamps and other low-income programs. And that’s why, more recently, Ryan and his allies have blocked efforts to extend emergency unemployment insurance. Doing so, they’ve said, will discourage the jobless from trying to find new work.

The evidence doesn’t really back up Ryan’s views. On unemployment benefits, for example, almost every study has found that any disincentive effects are minimal. But more striking (and less noticed) that what Ryan would do to the poor is what he wouldn’t do for them: Create jobs. Neither Ryan nor his colleagues in the Republican Party have a coherent, intellectually defensible agenda for creating jobs. Instead, they’ve argued for the same policies—reduced spending, taxes and regulations—that they always champion. And they reject ideas like infrastructure spending, more aid to the states, and short-term deficit spending that the majority of mainstream experts—including centrists as well as liberals—would endorse. Even if Ryan opposed all fiscal spending, he still could have supported monetary stimulus to jumpstart the economy. But he stuck to the Republican line there as well. In fact, the Republican Party has restricted job growth through their insistence on austere fiscal policy.

When it comes to the efficacy of antipoverty programs, Ryan may be right. But he cannot simultaneously demand spending cuts that have led to this anemic recovery and then use that as justification for cutting antipoverty programs. That’s circular reasoning and it proves nothing.