Mike Huckabee had asked me to send him my picture. He’d be sans entourage for our meeting at a Starbucks near Fox News’s midtown Manhattan headquarters, and he wanted to be able to pick me out of the crowd. Sure enough, at the appointed hour, he’s waving at me through the glass walls before he even makes it through the entrance. The barista line is long; since Huckabee hasn’t brought anyone to stand in it for him, coffee is forgone.

“We’ll do our work,” Huckabee says with a shrug. Later, after he realizes he has been droning on, he implores, “Stop me at any point and tell me, ‘You’re chasing too many rabbits out in the field here.’” Six years as a right-wing media host have not corroded the folksy charisma and self-deprecating wit that were hallmarks of his political persona. The man can charm.

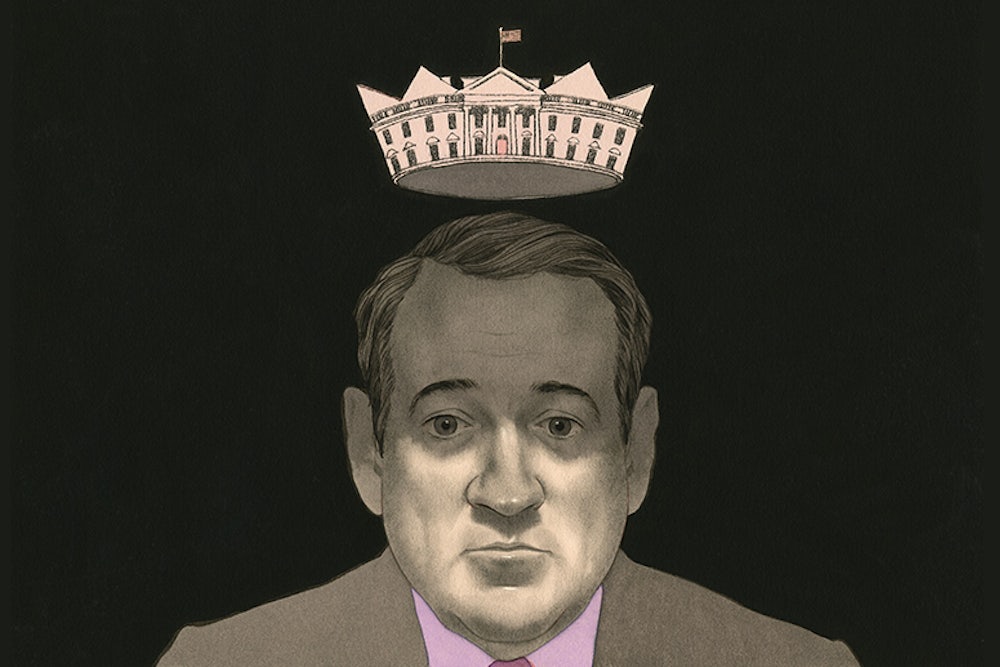

There are Republican kingmakers prepared to bank on just that. When Huckabee ran for president in 2008, the former Arkansas governor and Southern Baptist preacher beat expectations by winning the Iowa caucuses and finishing second in the overall delegate count. He passed on another run two years ago, when race-watchers thought the nomination was within his reach. But the 2016 election might present his best opening yet. Chris Christie is tarred by Bridgegate (etc., etc.). Scott Walker could wind up similarly tarnished by a slow-motion scandal of his own, involving public workers dispatched on campaign tasks. Ted Cruz and Rand Paul are ... Ted Cruz and Rand Paul. Meanwhile, early indicators suggest an appetite for Huckabee and his brand of conservative populism: This winter, at least four polls put him at the head of the primary pack—two of them even before Christie’s reputation tanked. The GOP strategists who told me they are urging Huckabee to run recalled how as governor he once earned more than 30 percent of the African American vote in Arkansas, where he also defended social services for immigrants. Huckabee, in this analysis, is the candidate who could bring back the party’s big tent. They hope to convince him to make another go.

Which might prove tempting for Huckabee, if not for the actual campaigning part. At a safe remove from filing deadlines, he has been happily granting interviews to reporters (including this one) to discuss his options. The process of running for office, though, is something “I actually dread,” he has said. And he’s not exactly clearing his schedule. This spring, he is slated to launch an ambitious, conservative-leaning news site called the Huckabee Post. A “major publisher” just bought his twelfth book. Other arms of Huckabee’s octopodian brand include animated American history DVDs and an annual guided tour of Israel, which for a base price of $4,999 offers travelers a “spiritual” experience and “special musical guests,” according to mikehuckabee.com.

“I’d hate to walk away from any of it,” Huckabee says. In fact, what he finds most appealing about a potential presidential bid seems to be the respite from multitasking: “I’ve really got about four or five full-time jobs. The one good thing about a campaign is that you have a singular focus. It’s the only thing you have to wake up every day and really, really think about. So that’s a plus.” This would be his most enthusiastic remark on the topic.

In Starbucks, the barista turns on the obligatory ’90s rock, starting with “Fly Away” by Lenny Kravitz. Huckabee’s right leg bounces while he answers my questions. He famously jogged off 100 pounds a decade ago but put back on a lot of weight after the 2008 campaign. “I hurt my knee and that messed up my running and boy did that ever just have a cascade effect,” he says. “I’ve gained about thirty pounds that my doctors have screamed at me about. I’ve got to get that off, and I know that.”

Motivation has been an issue for Huckabee the would-be candidate. Ed Rollins, a former Reagan adviser who pushed Huckabee to run last cycle, says he told him, “I can’t want this more than you do.” They met weekly for a year; Rollins considered Huckabee “as good a candidate as I’ve ever seen.” When Huckabee announced—on his own Fox News show, naturally—that “all the factors say go, but my heart says no,” a record 2.2 million viewers tuned in. Huckabee says he simply knew better than to underestimate President Obama: “His ground game was just exceptional.”

There won’t be an incumbent in 2016, but another variable remains in play. Were Huckabee to declare for the race, he’d have to give up his salary from Fox—$500,000 as of 2011—and many of his other income streams. He has called this “a big issue.” At one point, he jokes to me: “I want to be careful that I’m not announcing a candidacy here. Because that would be disastrous.”

During his years in the clergy and public office, Huckabee and his family got by on modest means. Enjoying his bigger paychecks, he and his wife, Janet, built a large house in the Florida panhandle in 2010. (The beaches are “whiter than this tabletop!” he exclaims, rapping the wobbly coffee-shop furniture.) His old sparring partners in the Arkansas press may joke that the Huckabee estate “looks like a La Quinta Inn,” as Max Brantley of the liberal Arkansas Times has heard it described. But the mortgage runs $2.8 million.

Along with personal financial pressures, there’s the matter of funding a campaign apparatus. Huckabee, who cobbled together just $16 million in 2008, is notoriously lousy on the donor circuit. “It feels so awkward,” he complains Huckabee has said he’ll only run in 2016 with the backing of deep-pocketed patrons and claims to be in touch with several major GOP financiers. But Republican fund-raisers caution not to read too much into that.“People are more likely to take his meetings now because he’s a celebrity,” said one. “For the same reason that, if Angelina Jolie called up and wanted to take a meeting, I’d take it.”

One theory about Huckabee holds that he ran in 2008 partly because he thought his years in Arkansas politics gave him special insight into facing Hillary Clinton. When I float the prospect of another chance to deploy that built-in advantage, he warms to the notion: “I certainly know the Clintons,” he says, “probably better than anyone in the Republican Party who might be involved in a race.” But as soon as he gets going, he rolls right off track.

“I’ve twice run against women opponents, and it’s a very different kind of approach,” he tells me. Different how? “For those of us who have some chivalry left, there’s a level of respect. ... You treat some things as a special treasure; you treat other things as common.” A male opponent is “common,” a woman requires “a sense of pedestal.”

“I’ll put it this way,” Huckabee says. “I treat my wife very differently than I treat my chums and my pals. I wouldn’t worry about calling them on Valentine’s Day, opening the door for them, or making sure they were OK.”

It’s not entirely accurate to say that Huckabee’s unmediated style gets him into trouble. It’s that plus his tendency to double down during the backlashes that inevitably ensue. In Arkansas, Huckabee called conservatives who disparaged him “Shiite Republicans,” and he remains quick to get his back up. Earlier this year, after he accused Democrats of thinking women “cannot control their libido” without birth control from “Uncle Sugar,” he kept the controversy alive by going eye-for-an-eye with critics.

“I refuse to let the Democrats, or the liberals, or somebody writing a blog dictate to me a lexicon of words I can use,” he says. He asks me to imagine that “you’re being told, ‘Nora, Here are some words you can and can’t use.’ Then your creativity is being stifled as a writer because it might upset someone!”

Huckabee has little use for such compromises. “I’m in this wonderful place of life,” he tells me, “where everything I’m doing is something I do because I enjoy it.” When he ran six years ago, a failed campaign gave him a new and more lucrative career. This time, there’s simply not as much upside. His daughter, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who was his field director in 2008, puts it this way: “You walk away from something that you love to do, and you may have nothing when you get finished.”

Plus, she notes: “What happens if you win? Then you’re the leader of the free world. It’s not an easy job. You have to be a lot more reserved. A little more disciplined. I don’t think he would enjoy that.”

I ask Huckabee what excites him about being commander-in-chief. “I don’t know that I’ve thought through that,” he replies. Most candidates “think they’re the only person who can do this job. I find that disturbing. I think it’s a form of megalomania. ... I don’t want someone being president who thinks that way.” Huckabee made a nearly identical comment in the winter of 2011, three months before announcing that he would not run.

Nora Caplan-Bricker is a staff writer at The New Republic.