Mr. Gandhi on the Future

January 6,1932

I was lucky enough to obtain one of the very few private interviews which Mahatma Gandhi granted while he was in England, seeing him only a few days before the Indian Conference came to an end in what Mr. Gandhi and his followers regarded as a tragic failure, and before he sailed back to India to prepare for a future dark with the likelihood of bloodshed on a terrible scale.

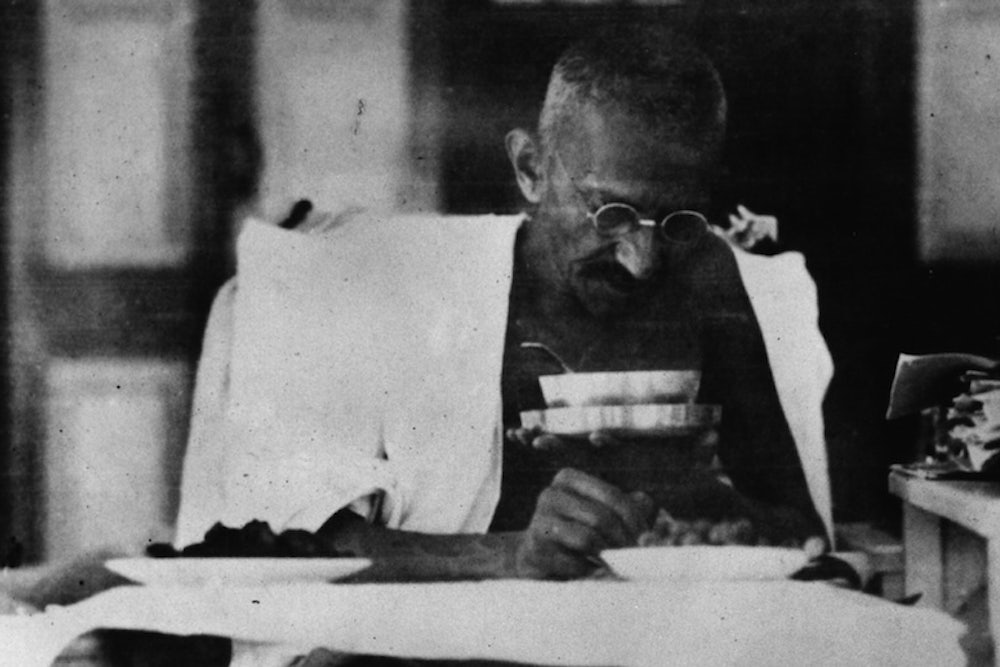

The interview took place, not in the settlement house where he slept, but in the home of a wealthy Indian, lent to him for use as an office. He received me in a large drawing-room full of conventional English furniture none of which he used. H e sat on the floor at one end of the room, buried in a huge, woolly white robe. The ubiquitous spinning wheel lay beside him—a flat varnished board, with simple cogs and spindle—and he thrust his spare brown hands out through the folds of his blanket and worked industriously while we talked. In the background sat two artists who were drawing him. In the next room, through an archway and partly concealed by a curtain, a stenographer took down in shorthand every word we said.

Mr. Gandhi paid no attention to the artists, turning his head constantly to the spinning wheel and then back to me as he answered, volubly and without hesitation, my barrage of questions. He looks (if there is anyone in the world by now who still does not know) incredibly frail, but lighted from within by that fire which has already cast its glow across such broad horizons. His large ears stand out straight from a round skull with the skin drawn tightly over the bone; his soft eyes be- hind the spectacles are lit always with the sense of humor which so often finds an almost mischievous utterance. Most of his teeth are gone, and this sometimes makes indistinct what he says in his high, very Hindu voice, even though his English is of the sort characterized as "Oxford," and much better than what Oxford usually hears.

I wasted little time in asking him about the conference itself, since his views are so well known to the world. Everyone is aware that he attended reluctantly and after repeatedly saying that he felt it was doomed to failure. The Hindus believed, and still believe, that the cards were stacked against them in advance, and that holding the conference was something like the appointment of the Wickersham Commission in America—less a sincere attempt to settle a difficult problem than a politician's way of postponing the solution while wriggling out from under the moral responsibility for that postponement. Instead of asking for his views on the conference, therefore, I tried to find out what he was thinking about the future of India if and when the British yoke has been shaken off. This was perhaps a little unfair—as unfair, say, as it would have been to ask Lenin in 1918 to visualize the Five Year Plan for Russia; but Mr. Gandhi showed himself entirely willing to answer inquiries of this character.

Replying to a question as to whether it would some day be desirable to have India’s independence guaranteed by the League of Nations or if the League should not survive till then) by a concert of the Great Powers, Mr. Gandhi promptly answered that such a thing was wholly unnecessary. If, he said in effect, the League wants to amuse itself by “guaranteeing” the freedom of India, we should have no objection to its doing so. But no one can win freedom for anybody else. The only real freedom is what you for yourself and hold by your own strength. I certainly hope that neither Japan nor, say, the United States (with an ironic glance), would ever try to gobble up a free India. But if they were to try it, the same methods of non-cooperation which we have applied against the English would be put into effect. The invaders would very quickly find that to hold the country would cost them more than they could possibly get out of it.

Mr. Gandhi recognizes that freedom from Great Britain would be far from solving all of India's problems. Among the most acute of these is, of course, the condition of the peasants who constitute such a large part of the population; they are crushed mercilessly by grasping landlords most of whom are themselves natives of India. Of the remainder, a large proportion are victims of industrialism, working in mills owned by native or foreign capitalists, with all the evils of unrestricted industry, long hours, small wages, child labor and absence of security. He believes, however, that the principles which are being learned in the fight with Great Britain will be successfully applied in the further fight for freedom on the part of the Indian population. He repeated what he had just said in another connection: no one can win freedom for anyone else. The yoke of the landlord, the yoke of the capitalist, will be shaken off when India is free from that of the "foreign invader."

I was interested to find that he did not agree with the statement often made by some of his followers, that the bad conditions in India are primarily the result of British rule. He believes that the British have taken advantage of the fight be- tAveen the liberal Hindus and the orthodox, conservative element, and have stood aloof when they ought, in accordance with their own theories, to have fought on the side of the liberals. But primarily, the admittedly bad conditions in India are due to the general state of the country, and can only be eradicated in the course of years. He remarked that some of these conditions are less serious than is commonly supposed, and mentioned the small percentage of literacy as an example. In India as elsewhere, he observed, wisdom and education are not synonymous: there are educated fools, and uneducated wise men.

His position in regard to machinery is often misunderstood, and he was at some pains to clarify it. I am not opposed to machinery, he said; and pointing to his spinning wheel, he added. You may re- port that you saw me using a machine, and a very good one, beautiful and simple. I do not care how big a machine may be; I only insist that man must be the master and not the slave, that it shall serve him and not the contrary. The objection to ma- chines in India has been that the men who worked them did so in the status of virtual slaves.

Mr. Gandhi commented readily upon another aspect of freedom, the difficulties raised by the Mohammedans and the "Untouchables," which, at least ostensibly, were the rock on which the Round Table Conference split. He observed, as he has done at other times, that the Hindus intended to give complete equality and justice to everyone. The minorities ought to be willing to wait and see, and if they felt they then had grievances, seek adjustment in an orderly way. But separate electorates, the new device introduced in India only a few years ago and mistakenly, would, if continued, simply produce an impossible, unworkable situation.

After some further desultory conversation, I began to feel somewhat conscience-stricken about the length of my visit and therefore asked him. Am I staying too long? His face broke into a broad grin and he made the perfect answer to this embarrassing inquiry: Everyone, he said, always stays too long. I picked up my hat and coat and said goodbye. As I went out the door, the artists pulled their chairs forward and worked, I thought, with fresh enthusiasm. Mr. Gandhi sat quite still on the floor, still huddled in his woolly white robe, his lean brown hands continuing, as though endowed with, an independent life of their own, to operate the silent, rapid mechanism of the spinning wheel—which, with the thousands of its fellows in India, is helping to break the heart of Lancashire, and is bringing the termination of the British Raj closer day by day.