The biggest surprise of Mitt, which debuts today at Sundance and premieres on Netflix January 24th, is that Mitt Romney makes a riveting subject for a documentary. The reason has nothing to do with any newly uncovered characterological insights or revelatory candor on Romney’s part. In the privacy of his ski-lodge-chic Utah home as at the debating podium, he has the same animatronic poise and patrician good humor. He uses words like “stumblebum.” He wears a "Salt Lake 2002" windbreaker while sledding with his family. “I don’t think we necessarily break any misnomers about the man,” filmmaker Greg Whiteley admitted on the phone. But Romney makes for one of the most interesting campaign documentary subjects in recent memory, simply because, in his pathological politeness, when it came to access he was seemingly unable to say no.

Whiteley, who is also a Mormon, started lobbying the Romneys to let him film them back in 2006. First he met with Tagg, who was moved by Whiteley’s entreaty but couldn’t persuade his father. But then Ann decided she liked the idea. So Whiteley got permission to attend Christmas with the Romneys in Park City, and from there he never stopped filming. The documentary begins on election night 2012, as the results are rolling in. The atmosphere is mingled gloom and relief; “Does someone have a number for the president?” Romney asks, with a pained half-smile. But then the film slides backward in time to another family scene—that first Christmas in Park City, with the whole clan sitting around the living room and listing the pros and cons of a presidential run.

If this documentary has a theme, it is: grandchildren. Romney spawn are everywhere, holding Mitt’s hand as he leaves the first presidential debate, toddling around him as he talks strategy with his sons, playing on the floor nearby while he bemoans the loss of Charlie Crist’s endorsement. New ones appear in every scene, like so much Ralph-Lauren-clad spillover from a tiny clown car. (Whiteley told me that over the course of the six years he spent filming, he could not believe how many Romney grandchildren there were. “It’s insane,” he said.)

And the film’s main revelation is that the family’s Hallmark public image seems to be pretty close to accurate. Ann is a sane and stabilizing presence, urging Mitt to “get a little something in [his] tummy” as they sit together in their hotel room before his first debate against Obama. When Romney nails one Republican debate, she looks about to faint from pride. “You knocked ‘em dead!” she says, and musses his hair. The square-jawed Romney sons, of which there are allegedly five, also make for likable characters. Their clear admiration for their father is the movie’s central humanizing force. Even their platitudes, i.e. “If you don’t win, we’ll still love you,” have the ring of simple, straight-faced truth.

In one of the documentary’s best scenes, Whiteley interviews a Romney son—I called them all “Tagg” in my notes, but this one appears to have been Josh—about whether he’s ever thought that the stress of the campaign trail wasn’t worth it. “You know it’s hard for me to do these interviews, because I’m so used to doing interviews with the media,” he says with a laugh. “Do the media version and then translate what’s really going on in your head,” Whiteley tells him. So Josh begins with a speech about how important his dad’s candidacy is to the country, and then shifts to real-talk: “This is why you can’t get good people to run for president. What better guy is there than my dad?....But you just get beat up constantly….You kinda go, man, is this worth it?” Even his off-the-cuff answer sounds somewhat canned, but by then the Romney school of chronic appropriateness has begun to seem oddly sweet. Their civility may be pre-programmed, but they mean it.

At first, Whiteley said, he was interested in making a documentary about Romney’s Mormonism. And the Mormonism is impossible to avoid; in Whiteley’s words, “you can’t film the Romneys for 12 hours without filming a prayer.” But the religious aspect proved less interesting than he’d thought. And as Romney’s profile rose in the political world, Whiteley found he could barely get any access to his campaign staffers. “That was something that used to make me feel insecure about the movie,” Whiteley said. But in the end it forced him to feature the family, which was ultimately his luckiest stroke. And throughout the whole ordeal, he had remarkably little difficulty accessing Romney himself.

He recalls that when they all arrived in Vegas for a day of campaigning, the plane landed at 2 a.m. and Whiteley hopped into the car back to the hotel with Romney, which somehow raised no objections. And then, as Romney walked down the hotel hallway flanked by a whole team of advisers, the staff peeled off one by one—but Whiteley followed Romney into his room and kept asking questions, which an exhausted Romney gamely answered.

Whiteley took an extended break from filming in 2008, and the ratcheted-up stakes in Romney’s second stint on the campaign trail make for a stark contrast. In one early scene, the family eats at a restaurant while Whiteley approaches some diners and informs them that they are sitting next to a presidential candidate. “Sorry guys,” says Mitt, swiveling around to confront their blank faces. “I’m running for president.” So an hour into the film, it is genuinely exciting to see him summoning as much awe as the president himself. "They're even bigger in person," says a young man in 2012 as Romney and Paul Ryan make smalltalk nearby.

But as a campaign documentary, Mitt has none of the logistical intricacy of The War Room (about Clinton’s 1992 race) or Street Fight (Cory Booker’s 2002 mayoral bid in Newark). In fact, the actual mechanics of campaigning are notably absent. Though Whiteley is present at many politically crucial moments—before and after both presidential debates, through some of the fallout from the 47 percent gaffe, during the election night moment where Romney drafts his concession speech—Romney never seems more than mildly distressed about the actual prospect of losing. It’s a family drama much more than a campaign drama, and Whiteley’s willingness to embrace that fact is the source of the film’s unexpected warmth. In one scene, the Romneys sit together at the kitchen table laughing loudly, and somewhat uncannily, at a David Sedaris monologue on “This American Life.”

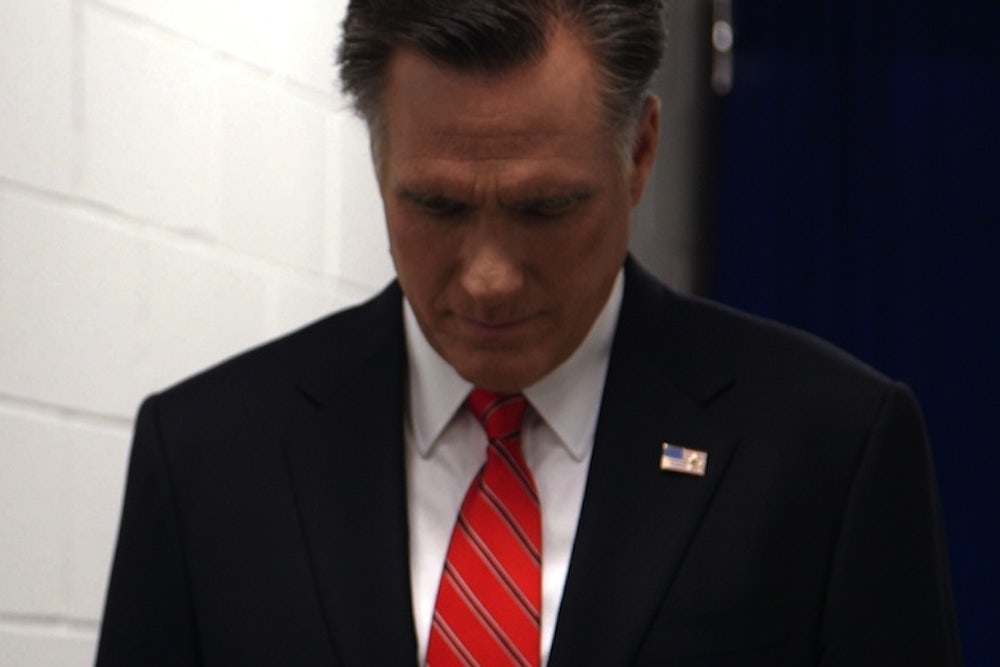

Mitt does not exactly save Romney from his reputation as a robot. But his formality begins to look less like an artifice and more like a kind of dorky tic that binds the Romneys, like a well-intentioned, alien tribe, against the larger world. In one scene from his 2008 campaign, Matt Lauer interviews Romney on NBC. Lauer had been scheduled to travel to Dearborn, Michigan, to do the interview in person, but a storm grounded his plane in New York. So while the split-screen on NBC is a close-up of Romney’s face, Whiteley’s camera finds him standing in a huge, deserted auditorium, looking as stiff as ever, his hands clenched at his sides. And yet there is something newly sympathetic about the sight of him alone in that empty hall. “My rule was that I was going to keep filming until Mitt told me no,” Whiteley said. “Everybody who was not a Romney told me no. Everyone else told me, ‘you’re not welcome here.’” But Romney, he said, “is polite to a fault.”